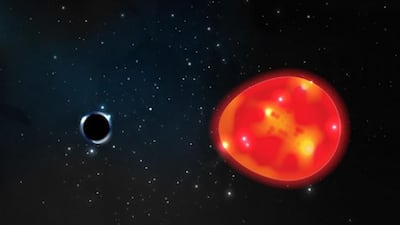

Astronomers have found the closest-known black hole to the Earth, lurking near a star on our cosmic doorstep. Called "The Unicorn", the bizarre object is about 1,500 light-years away and has a mass of six billion billion billion tonnes – three times that of our sun – crammed into a space just 20 kilometres across. Astronomers are racing to find out more about the object, because its very existence could cast new light on the birth of black holes.

Why 'The Unicorn'?

Because even by black hole standards, it is an unusual beast. Until now, all known black holes have been at least five times more massive than the Sun. For years astronomers could not decide if this meant there is some mysterious law of nature compelling black holes to be at least this big, or whether they had simply not looked long and hard enough to discover smaller ones. Now they believe they have found one – and, by coincidence, it lies in the constellation called Monoceros – Greek for “unicorn”.

How did it get there?

No one knows for certain. Astronomers believe black holes are typically formed when a giant star runs out of nuclear fuel and starts to collapse under its own gravity. This usually triggers a catastrophic supernova explosion that leaves behind a neutron star a few tens of kilometres across. But sometimes, for reasons that are still unclear, there is no explosion, and the giant star carries on collapsing until it forms a black hole. The Unicorn seems to be the remnants of the long-vanished companion of the giant star lying next to it.

As black holes are invisible, how was it found?

As they cram so much mass into so small a volume, black holes have gravitational fields so intense nothing – not even light – can escape their clutches. Even so, black holes can reveal their existence through the effects of their titanic gravity on their surroundings. Colossal black holes with masses billions of times that of the sun have been found at the centres of galaxies through their effect on orbiting stars.

In the case of The Unicorn, its existence was revealed through its effect on its stellar neighbour, which is being hurled around by some invisible companion. Results published by an international team led by Ohio State University doctoral student Tharindu Jayasinghe show that the two objects are whirling around each other every 60 days. Detailed analysis of their motion revealed the The Unicorn to be three times more massive than its companion.

How do they know it’s the closest-known black hole?

This is not the first time astronomers have claimed to have found a black hole on our cosmic doorstep. Last year another team of astronomers said they found a small black hole in a star system visible to the naked eye, 1,000 light-years from the Earth. But studies now suggest the "black hole" is really a small family of ordinary stars.

The new claim is even more controversial, because the mass of the supposed black hole is very close to the maximum for that of a neutron star – a much less spectacular claim. In their study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society journal, the team examines more than a dozen other possible explanations for their observations, and concludes a small black hole is the most plausible.

Could there be even closer black holes?

Quite possibly. During the early history of the universe, formed in the Big Bang 14 billion years ago, there were huge numbers of vast, sort-lived supergiant stars that may have spawned black holes that are still wandering through space. The Big Bang itself may also have given birth to swarms of tiny black holes.

Some astronomers claimed that such a small black hole may already be lurking on the edge of our own solar system. With a mass about 10 times that of the Earth, the black hole would be 20 centimetres across – the size of a football – but could account for the strange behaviour of objects orbiting far from the Sun. Even if a black hole came only within a few light-years of the Sun, it could stir up the cloud of comets surrounding our solar system. This could lead to a devastating wave of impacts of the kind implicated in the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Robert Matthews is visiting professor of science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK