As engineers prepare the UAE’s first mission to Mars for blast-off next summer, it’s clear the timing could not be better.

The Hope probe was originally scheduled to reach the planet in 2021, in time for the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Emirates.

But a slew of new discoveries about Mars means the UAE’s mission will arrive just as excitement about the Red Planet reaches fever-pitch.

Speculation about the possibility of life on Mars has ebbed and flowed for centuries. In the 1700s astronomers noted seasonal changes in the planet’s appearance – hinting at life responding to changing conditions.

In the late 1800s came reports of canal-like structures being seen by telescopes. That prompted talk of Martian engineers until the images were debunked as optical illusions.

But the chances of finding anything alive on the Red Planet plunged after the first-ever fly-by in 1964. Nasa’s Mariner 4 probe revealed an arid, barren, battered planet.

Combined with its thin atmosphere choked with carbon dioxide and intense ultra-violet radiation, most scientists gave up hope of life on Mars.

Yet since then, an armada of satellites, landers and rovers have probed the planet with ever more sophisticated instruments.

And now they have found Mars has everything needed for a planet to support life.

Astrobiologists point to three crucial requirements: a source of energy, water and chemistry consistent with the existence of organisms.

The sun is the key energy source for life on Earth, and while Mars is further away, data from landers show temperatures can exceed 35 deg C.

Detailed mapping of the surface has also found evidence of volcanic activity suggesting the interior of the Red Planet was once very hot.

Satellites and landers have also found compelling evidence that water has flowed over the surface of Mars, ranging from what look like vast river canyons and dried-up streams to gravel apparently eroded by water.

And last year, the European mission Mars Express detected a vast lake of liquid water trapped some 1,500 metres below the planet’s south pole.

Now the final piece of the jigsaw is sliding into place, with the discovery of chemistry of the kind often linked to living organisms.

Even before Mariner 4’s discouraging images, scientists were writing off life on Mars because of its chemical “fingerprint”. Earth-bound studies suggested its atmosphere lacked highly reactive chemicals like oxygen and methane.

On Earth, these are constantly replenished by the action of living organisms, such as photosynthesis and rotting.

But the atmosphere of Mars consists almost entirely of unreactive carbon dioxide, suggesting any organisms producing fresh reactive gases were dead - if they ever existed.

Yet there’s an obvious flaw with that argument: perhaps the concentrations were just too low to detect from Earth.

Confirmation of this emerged in 2004, when the newly-arrived Mars Express picked up traces of methane in the atmosphere.

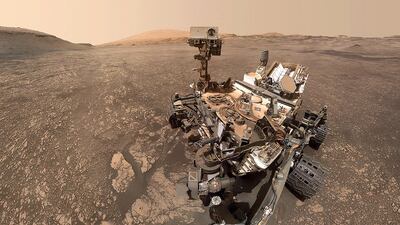

But last year Nasa announced a new twist. Its Curiosity rover had sniffed out methane and found a pattern: levels of the gas peaked in the Martian summer and then died away in winter. Sudden bursts of the gas were also detected, the biggest appearing this June.

Mission scientists admit they have no explanation – though one seems obvious: Martian organisms responding to the changing seasons.

Now they’re facing another mystery, this time involving the best-known life-giving gas: oxygen.

Nasa has just revealed that Curiosity has been monitoring levels of oxygen for three Martian years – equivalent to five and a half Earth-years.

And they’ve found another seasonal pattern, with oxygen levels rising in spring and summer, then fading in autumn, just like the methane.

Announcing their discovery, the scientists struggled to hide their excitement. “The first time we saw that, it was just mind-boggling”, said Professor Sushil Atreya of the University of Michigan. “I think there’s something to it. I just don’t have the answers yet. Nobody does.”

One thing’s for sure: there won’t be any definitive statements any time soon, as Mars has a reputation for sparking bitter disputes.

In the mid-1970s, Nasa sent two probes to the planet fitted with on-board labs for testing soil for signs of life – some of which were positive.

Officially, Nasa insisted the results were likely due to weird chemical reactions rather than organisms. But some scientists, including one of the team that created the tests, insisted the most plausible explanation was Martian microbes.

In 1996, Nasa scientists claimed to have found fossilised microbes in a meteorite from Mars. The claim, based on images of microscopic worm-like objects, made headlines worldwide. Even President Bill Clinton held a press conference to express his excitement.

But other scientists quickly dismissed the “evidence” as subjective. It’s now generally regarded as intriguing but unconvincing.

Just last month, a retired professor at Ohio University went public with fuzzy images of what he claimed were creatures photographed near Nasa's Curiosity rover.

While Professor William Romoser insisted “there has been and still is life on Mars”, his own university deleted the press release – though not before it had been ridiculed in the media.

With professional reputations on the line – as well as funding for future missions – scientists involved in Mars missions are typically very circumspect about making grand claims for their findings.

The team behind the UAE's Hope mission will doubtless be the same. In truth, it's unlikely they will face the dilemma of deciding whether to go public with evidence for life on Mars.

The Hope satellite is designed to stay in orbit for at least two years and study the climate of Mars. It's important work, but Hope wasn't designed to carry out tests for life on the planet.

Yet history shows it’s foolish to predict what scientists might find when they dare to probe the secrets of the Red Planet.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK