Imagine being able to read a novel or a non-fiction book at, say, one-and-a-half times the normal reading speed.

So, instead of an average-length novel taking more than five hours to read — assuming a reading speed of around 250 words per minute and a novel of 80,000 words — it could be polished off in a little over three-and-a-half hours.

While the idea of speed reading has been around since at least 1925, when a course on the subject was taught at a university in New York, in today’s world people who want to read faster may look to technology to help.

One app in particular, Bionic Reading, has been generating headlines.

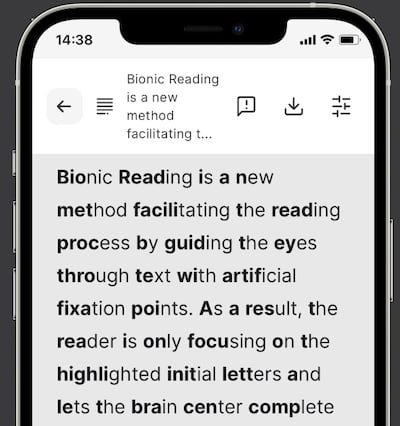

The app, which reportedly has users across the world, creates what its owners call "artificial fixation points" that guide the reader through the text.

The first few letters of each word are highlighted in bold, allowing the brain to complete each word and facilitating, the app states, "a more in-depth reading and understanding of written content".

The app’s webpage lists people who could benefit from such a reading technique as, among others, someone with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and others who have little free time.

Among those who have welcomed its arrival is Dr Dean Burnett, an honorary research associate at Cardiff University’s School of Psychology in the UK, and author of books including The Idiot Brain and The Happy Brain.

He finds material written in bionic text "a bit easier to read" and describes it as a "brain hack" that exploits the way our visual systems work.

New tech can be useful

"It’s all about eye movements," he said. "Brain power is incredibly demanding for the body, so anything which helps it skip a step or limits the amount of information it has to work with, is usually quite effective.

"I think bionic text does that. It does give your visual system anchors to focus on, so I can certainly see how it might be a more efficient way to read, a more palatable way to read, for people who have sensory issues or are neurodivergent, like ADHD, and the brain has to work hard anyway to keep focus."

A concern that has frequently been raised is that there is little data to support the suggestion that bionic reading enables people to read more easily or faster. One study tested more than 2,000 readers and actually found a very slight decrease in reading speed.

With speed reading in its non-bionic form having been practised for many decades at least, it comes as no surprise that there have been some high-profile adherents over the years, among them the late US president John F Kennedy, who was said to have been able to read at 1,200 words per minute (wpm).

One of his successors, Jimmy Carter, was also a fan. A course Mr Carter took during his time in the White House helped him to "greatly improve my speed reading and comprehension", the former president said in 2012.

Rapid reading

Few people take a closer interest in speed reading than Peter Roesler, author of the book Principles of Speed Reading and chair of the German Society for Speed Reading.

With a number of weeks of training, he said a person who reads at 250 wpm may be able to increase their speed by about 150. Described as basic speed reading, this is achievable by about 90 per cent of readers, he said.

Beyond this, there have been wild claims by others of reading speeds of as much as 15,000 wpm or even higher, although Mr Roesler said these were likely to be impossible because this much information cannot be transported by the visual system to the brain.

"Reading researchers usually say speed reading does not work, and it’s true for most of the claims, but there’s good scientific evidence for the smaller claims that it works," he said.

"It takes a long time to improve the relevant brain areas and in the lower rates it is mainly the inner voice which is the limiting factor."

If this "inner voice" is no longer active, Mr Roesler said that reading speeds of up to 900 wpm could be achieved through visual line reading, in which the person understands what has been read without the need for certain brain areas to be activated. Other techniques can, he said, achieve speeds of up to 1,500 wpm.

Whether bionic reading should be considered a valuable way of improving reading speed, appears uncertain, however.

Better to take it slow

Certainly some researchers think that it brings no benefits. Dr Lauren Trakhman, an assistant clinical professor in the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland in the US, suggested it was not helpful for any reader and could even prove harmful to the reading of people with ADHD or related difficulties.

"One of the most helpful tools for readers with ADHD is to read more slowly, which is the antithesis of bionic reading’s entire argument," she said.

Another academic, Dr Mary Dyson, a senior visiting research fellow in the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading in the UK, said that the way that bionic reading highlighted certain letters may not take proper account of eye movements in reading.

In a normal reading environment, she said the initial saccade (movement of the eye between fixation points) tended to place the eyes just left of the centre of the word.

She also said that no account was taken of the varying difficulty of words, which affects how long the eyes fixate words, and which words a person might skip.

Dr Dyson thought it unlikely that the app would increase reading speed and, if it did, she predicted a reduction in comprehension.

Concerns about a loss of comprehension are common with speed reading, creating what may be described as the speed-accuracy trade off.

Research Dr Trakhman and her colleagues has carried out indicates that the only time where reading more quickly is equal to reading at a normal speed is when a person is trying to get just the main idea or gist of something.

"So, bionic reading would be a fine use if, say, you needed the news headlines quickly before entering a dinner party where you wanted to sound aware of what was going on in the world," she said.

"For anything more than comprehension on a superficial level, it shouldn’t be used."

While speed reading, whether bionic or otherwise, may be valuable in certain situations, such as when trying to take in the salient points from a lengthy text, it is probably best put aside when, say, tackling a novel.

"If you’re trying to read a novel for pleasure, you won’t get what you need from it," Dr Burnett said. "The whole point of the novel is that you’re immersed in that world.

"You’re taking in the story, the nuance, the subtlety, and speed reading will prevent your ability to do that because the information is too much for your brain to take in and work through."