Since landing on the surface of Mars a year ago, Nasa’s Perseverance rover has collected rock samples that, when eventually brought to Earth and analysed, offer researchers the chance to find signs of past life on the red planet.

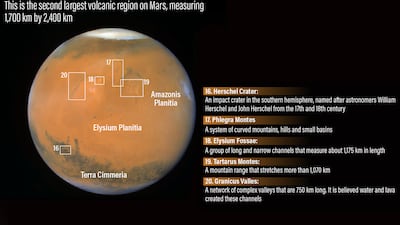

But as well as asking whether there was life on Mars, scientists are grappling with other equally fascinating issues: is the interior of Mars still molten — and could the planet become volcanically active again?

The UAE’s Hope orbiter is producing stunning images of Mars and will offer information about the planet's weather patterns, but it is other orbiters and landers that have provided the data that scientists are currently analysing to understand patterns of volcanic activity.

Washington University, St. Louis

Like Earth, Mars was formed just over 4.5bn years ago and, earlier on, it definitely contained molten material, some of which was released at the surface through volcanoes.

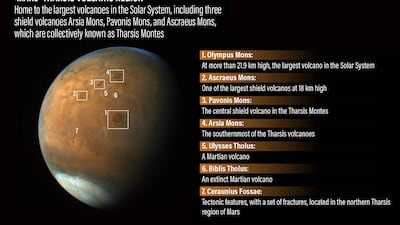

One of Mars’s volcanoes, Olympus Mons, is the biggest in the solar system, towering 16 miles high and with a diameter of almost 375 miles.

“We know that Mars has a long history of volcanic activity, of tectonic activity,” said Dr Paul Byrne, an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

“It has gigantic scarps that are tectonic that resulted from quakes. It has vast lava plains. We know there’s been a lot of geological activity, but a lot of that activity is very old.”

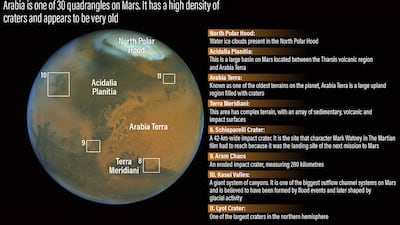

Further evidence of ancient volcanic activity on Mars came last year from analysis of the Arabia Terra region of Mars using images from Nasa’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

A study released in September found that the distribution of minerals on Arabia Terra was consistent with material being thrown out of volcanic craters or calderas over a 500-million-year period about four billion years ago.

While Earth has about 40 active volcanoes, Mars is smaller and so may more quickly have lost the heat they had on formation. But even if it is less geologically active than Earth, Mars may still have molten material underneath its surface.

“We know that Mars is not going to be a volcanic powerhouse like Earth is,” said Dr Byrne.

“Worlds that are small shut down early. Most of Mars’s geology is now over fundamentally, but there’s this long coda, tail at the end.”

A 2021 study that looked at results from the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter may offer clues about present-day volcanism. The orbiter, a joint project by the European Space Agency and Russia’s Roscosmos, detected hydrogen chloride (HCl), a gas given off by volcanoes.

Whether this indicates that there is current volcanic activity is, however, unclear, according to Dr Kevin Olsen, of the University of Oxford, who analysed data on how the Martian atmosphere absorbs sunlight to identify the presence of the gas.

HCl was found only seasonally, being associated with dust storms, so its presence could result from the chemical composition of the minerals on Mars’s surface rather than from volcanism.

Two other studies using ExoMars data and published last year by colleagues of Dr Olsen did not find evidence of methane or sulphur dioxide, both of which are linked to volcanic activity.

Dr Olsen said that he and his co-researchers have yet to fully understand what is behind the things they have observed.

“It’s very mysterious still,” he said.

“The chemistry that we talk about can’t explain how HCl disappears every season. We have some very good ideas that we are now testing.

“It is possible, said Dr Olsen, that pockets of gas associated with magma are being released on a seasonal basis, perhaps because they cannot emerge during the Martian winter.”

It could be some subsurface gas release related to the freezing and thawing cycle. Maybe not a volcano, but lots of distributed seeps that may only be active in the summer because otherwise they’re covered by ice,” he said.

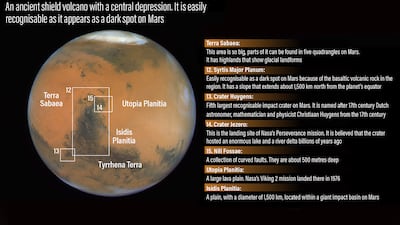

Nasa’s InSight lander, which touched down on Mars in late 2018, has offered useful information about Mars’s geological activities, detecting hundreds of marsquakes. In August and September 2021, InSight detected the three biggest marsquakes recorded so far.

A minority may originate within the Martian mantle, while the rest may be shallower, coming from the planet’s crust.

“These quakes are direct evidence that there is seismic activity on Mars today,” said Dr Anna Horleston, a research associate in planetary seismology at the University of Bristol in the UK, who co-leads the MarsQuake Service, which analyses InSight’s seismic data.

Mars does not have plate tectonics, which causes severe earthquakes, but it does have stresses from, for example, the “extreme highs and lows” of its topography. Dr Horleston said these could explain much of the detected seismic activity.

The huge mass of the likes of Olympus Mons creates pressure on the mantle (the section beneath the crust), which propagates into the nearby mantle and crust, causing cracking.

“These cracks or faults remain under tension and occasionally they release that stress,” she said.

Some marsquakes originate from Cerberus Fossae, a geologically recent area made of cracks or faults in the ground that extend for more than 1000km.

“It is not thought that this region is currently volcanically active but there is certainly stress within the crust around the faults and the quakes we have recorded are evidence of this,” said Dr Horleston.

Signals from Cerberus Fossae detected by InSight also indicate fluid moving through the subsurface, said Dr Nicholas Schmerr, an associate professor in the Department of Geology at the University of Maryland and a participating scientist on the InSight mission.

Fluid moving through a pipe or a fracture gives off a characteristic frequency of energy, he explained, something like a tone.

“We’ve seen some signals from this region that could be modelled as essentially that kind of magma flow through the subsurface. It’s not conclusive, but it’s definitely one of the possible mechanisms that could be at play there,” he said.

Instruments located nearer to the source of the signals could provide more definitive evidence, but even the results so far, while not absolutely confirming the presence of magma, have caused excitement among researchers.

“If it’s going to come to the surface and erupt I can’t really say but it’s there, potentially, so that’s kind of exciting to think that Mars is still stewing away at depth,” said Dr Schmerr.

“It’s not like the Earth, where it’s super active, but maybe there are a couple of places that could still potentially be active in future.”

Dr Byrne too is upbeat that data from InSight indicates that there could be magma moving inside Mars, saying he would be “very surprised if it turned out in the final assessment” that this was not the case. Planets, he said, “cool slowly”.

“The idea that there is magma moving and slowly ascending and jostling and then cooling in the subsurface, I don’t think that’s all that surprising. It’s just very gratifying to be able to actually detect potential evidence of it,” he said.

However, when it comes to the chance of any future volcanic activity on the Red Planet, the timescales involved are such that we shouldn’t expect anything soon.

“If a volcano on Mars erupts every million years, that might be fairly regular, now, for a planet that’s 4.5bn years old,” he said.

“We might yet still see new eruptions on Mars, we just probably won’t see them in our lifetime.”