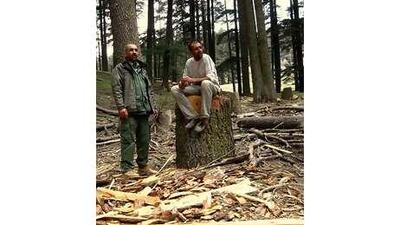

IDIKEL FOREST, MOROCCO // It was a damp, drizzly afternoon in the forest of Idikel, in Morocco's High Atlas Mountains, and two men were counting the rings in the stump of a purloined cedar.

"One hundred ? 110 ? I make it at least 120 years old," said Mustapha Hafid, a state forestry agent. Beside him, Mustapha Allaoui, a conservationist campaigner from the nearby village of Tikajouine, sighed with frustration. A war of sorts is raging in the Idikel forest. On one side are impoverished villagers, mainly from Tikajouine, who illegally harvest valuable cedar wood. On the other are their conservation-minded neighbours, who are struggling to stop the logging they say endangers the village's future.

"Our lives are linked to the forest," Mr Allaoui said. "If it disappears, we'll have to move to the city." For decades, rural poor from across Morocco have fled to big cities from villages like Tikajouine, low on prospects and high on unemployment. There are houses of pounded earth crowding a stream that rushes out of the mountains, a tangle of dirt roads, a mosque, a primary school and not much else.

Below the village are fields of wheat and potatoes. Towering above it are the mountainsides where Tikajouine's 4,200 inhabitants graze sheep and collect firewood for cooking and heating. They belong to the Ait Hnini, one of dozens of tribes of Amazigh, or Berbers, who have lived in North Africa since before the start of recorded history. The Atlas Mountains were often part of the "bled siba", or land of dissidence, a term for regions periodically outside the control of Morocco's rulers until France colonised the country from 1912. The area around Tikajouine was not fully subjugated until the 1920s.

By then, Morocco's forests had been placed under state management. Today, the law reserves 80 per cent of proceeds from state sales of timber for use by local municipalities, Mr Hafid, the forestry agent, said. However, in recent years farmers from Tikajouine and other villages have begun stealing into the Idikel forest by night, sawing down cedar trees and selling the valuable wood to black market traffickers. In the morning there are only stumps, mule tracks and chips of red-blond wood.

Mr Hafid patrols the forest's 4,700 hectares with a fellow forestry agent, a dog and a white 4 x 4. "I can't arrest people, but I can serve them with fines up to 10,000 Moroccan dirhams [Dh4,000]," he said. "Unfortunately, the courts don't always follow through, and I can't be everywhere at once." That is why some locals in Tikajouine have stepped into the gap. "I was born in the forest," said Said Ait Aziz, a member with Mr Allaoui of the conservationist Idikel Association. "I grew up leading my family's sheep under the trees."

For years Mr Ait Aziz has documented the theft of trees and campaigned for their protection. One night in 2008, he narrowly escaped a fire in his house he believes was set by vengeful woodsmen. Last year, Mr Ait Aziz began working as a part-time night watchman in the forest through a pilot programme financed by the state forestry agency. Funding ended in February, but conservationists say the effort has already made a difference.

"A few years ago, the woodsmen were stealing 20 to 30 trees a day," Mr Allaoui said. "The situation today is a clear improvement." According to Mr Hafid, only 79 trees were felled illegally last year. The Idikel Association has requested state permission to create a woodsmen's collective to gather deadfall and dying trees for sale, which is legal. "The municipality has done nothing for the community," Ali Ouaadi, the group's president, said. "With a collective, everyone benefits legally from the forest."

But the proposal has drawn opposition from the municipality president, Said el Kortoubi, one of several officials whose approval is required. "The forest simply isn't big enough to support a collective. It might work for a year or so, but it doesn't have a future," he said. For many woodsmen, the main issue is money. "I make 10,000 dirhams a month," said Bou Maksou, 27, a woodsman who asked to be identified only by the part of the forest where he often works. "I can't earn that from a collective."

Night was falling on Tikajouine, and Bou Maksou was sitting in a cafe with the chief of his logging crew at a meeting with The National arranged by human rights workers. A naked bulb cast a sickly light on the men. "I worked as a shepherd in the forest and I saw what was going on there, and I fell into the trap," said Bou Maksou, who began stealing trees eight years ago. "I don't want to keep living like this, without a wife, without children, without normal employment." The crew chief glanced at his watch and the two men rose. "It's getting late," he said. "We need to get to the forest." @Email:jthorne@thenational.ae