The residents of the Micronesian nation of Palau are less than thrilled about their latest immigrants: 14 Uighur men cleared of terrorism charges and released from Guantanamo. Martha Ann Overland reports. Tropical rains wail against the tin roof of the ramshackle Palau Baptist Church, but the pounding can't dampen the fervour of the pastor preaching to his congregation on this small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. "What is a bribe?" Pastor Terrence McClure asks, addressing several dozen followers who are seated on plastic chairs with Bibles in hand. With his voice rising above the thrumming rain, he explains: "If a friend gives you a gift to buy them off, then that's prostitution. Gifts are not free." He urges his congregation to ask themselves when they are offered a present: "Is this a gift or is this a bribe?"

McClure's sermon seems particularly apt, considering that many in this small island nation are wondering the very same thing about their government's recent agreement to take in more than a dozen Uighur Muslims being held in the US military prison in Guantanamo Bay. The announcement coincides with the renegotiation of a compact between Palau and the United States, which has been reported to include a payment of some $200 million in badly needed aid to the small nation. Both governments, however, deny that the two matters are in any way connected.

The money has done little to ease concerns for Ryan Mikel, a boat and tour operator in Palau. His country is in dire financial straits but money doesn't buy peace of mind, he says as he takes a break from watching an American baseball game on television at the popular Rock Island Bar and Grill in Koror, Palau's largest city. Mikel had heard that the Uighurs had been cleared of terror charges by the United States. But suspicions about the Chinese citizens, who were arrested in Pakistan and Afghanistan in 2001, remain. "If the United States refused to take them, then why should we?" asks Mikel. "When people think Muslims, they think terrorism."

Finding a home for the Uighurs has been among the many vexing challenges facing American officials determined to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay. The US has reportedly approached more than 100 countries seeking a home for the men, who have languished in prison for seven years. It is widely believed that they would face torture or death if they returned home, where ethnic Uighurs are fighting separatist battles with China, but speculation that they might be resettled in America was quashed after a huge outcry from several US congressmen.

Palau is a long way from the barren deserts and high mountains of Xinjiang, the vast western province home to China's Uighur minority. This predominately Christian nation of more than 250 islands - most of them uninhabited - near the equator is best known for its pristine beaches, lush tropical forests and world-class diving. The country proudly boasts that it has hosted the American reality show Survivor not once but twice.

The country depends heavily on tourism and handouts from the United States, which provides roughly half the annual operating budget. Palau became a US protectorate after the Second World War. Since gaining its independence in 1994, Palau has received financial support under a compact that grants the US basing rights and defence authority over the islands. Palau citizens don't need a visa to travel to the US, and many attend university in America or enter the US military.

Earlier this week, the first Palauan to be killed while serving in the US Army in Afghanistan was buried in his hometown. Sergeant Jasper Obakrairur was killed on June 1 by a homemade bomb while he was out on patrol. Obakrairur was given a state funeral with full US military honours, including the Purple Heart. The ceremony was attended not only by Palau's president and senior leaders, but also by a large contingent of US Army personnel.

Palau's close relationship with the United States has given the tropical island a distinctly American flavour. The roads, most of them funded by US taxpayers, are lined with small shopping centres packed with local mom-and-pop stores alongside distinctly American brand name stores, such as The Athlete's Foot - where you can only pay for your new pair of running shoes with American dollars. Convenience stores are packed with Doritos and Duncan Hines cake mixes. Sandwiches made with fried Spam, an iconic American canned luncheon meat, are a staple on practically every restaurant menu.

With just 20,000 people, Palau is more like a small town than a small country. It's the kind of place where you don't worry about leaving your keys in your car when you run into the post office - which still has a US postcode: 96940. Despite the fact that the population is spread across eight islands, some of them hundreds of miles apart, everyone seems to know everyone else. After asking someone out on a date, jokes a hotel driver, young people always check with their parents to make sure they aren't related.

The most scathing public criticism thus far of President Johnson Toribiong's agreement to take in the Uighurs came from his own brother-in-law. In an editorial in the Island Times, Fermin Nariang wrote that the decision will "negate years and millions of dollars worth of marketing and promoting Palau as a safe, friendly and family destination". Nariang accused the Palauan president of doing it solely for the cash. "Why not agree to accept 100 [Uighurs] in exchange for a billion bucks?" Nariang asked in jest. "Now that is the kind of deal that will shut the mouth of a naysayer."

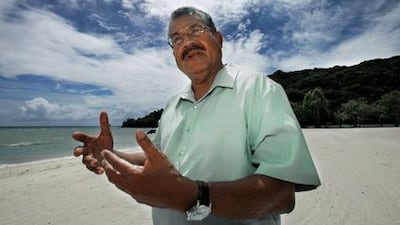

One recent morning, President Toribiong greets visitors at the gate of his humble bungalow on a jungle hillside, laughing, "Welcome to the White House!" He is dressed in a smart suit and tie for a meeting with an American military delegation who have just arrived. But it is easy to imagine him snorkelling or spear fishing - his favourite forms of exercise, he says. Still, Toribiong is no country bumpkin. He got involved in Palauan politics shortly after returning home with a law degree from the University of Washington. Toribiong helped write Palau's first constitution back in 1981, when the country was still under the trusteeship of the United Nations. In fact, says the president, his decision to take the Uighurs was a reflection of the principles of "human rights and freedom" upon which the Palau constitution is based.

"We were advised if they returned to their homeland they would be tortured or even killed," he says. "Our acceptance of the request was to advance the course of justice. These people were caught between a rock and a hard place. It's not only just, it's morally right." Toribiong concedes that he has taken some heat, largely from people who are ignorant about the Uighurs. (The government is now working to get the word out.) But he says that the top leadership, including the village chiefs, who have great influence in Palau, is behind him one hundred per cent. The president denies that the $200 million from the US made a difference in his decision. In fact, it was an honour, he says, to help out a loyal partner and friend that has done so much for Palau.

And what about his brother-in-law's fierce rebuke in the local newspaper? Toribiong insists there are no hard feelings. "I wrote him a letter and I said I respect your right to express your opinion," he says. "But I still love you."

Sam Scott, the American owner of Sam's Tours, a major employer on the island, squirms at the mention of the Uighurs. As his boats pull in to unload scuba divers from a day at sea, he says the decision has already tarnished Palau's pristine image as tropical paradise far from the worries of the rest of the world. "I've received e-mails that said specifically, 'We are cancelling and looking elsewhere because of the Uighurs,'" he says. Palau is already suffering, Scott adds. The country caters to high-end tourists, and the global economic slump has hit the luxury travel market particularly hard. Another recent blow to tourism has been the H1N1 virus, also known as swine flu. Now it's the Uighurs, complains Scott, who has been living in Palau for the past 27 years. "Palau's image is important to us in the tourist industry," says Scott. "I think we are making a mistake here. Leave well enough alone."

Not everyone thinks taking in the Uighurs is a mistake. Yes, the country does need the money. But Palau also has a long tradition of taking in those who find themselves shipwrecked on its shores. The president calls them "drift relatives". Indeed, the number of foreigners in Palau now outnumber those who were born here. Most are Filipinos who come here on short contracts to work in the hotel and diving industry. But the second largest population of foreigners are Bangladeshis, who are also Muslim and, according to many local residents, cause no problems.

Mayumi Lomongo is a retired postmistress who was born in Palau but attended university and lived for many years in Hawaii. She believes that her fellow Palauans have been too quick to judge the Uighurs: the terrorist label is a hard one to shake. "I hear people at the market saying they are terrorists," says Lomongo. But she believes few people know the truth about the detainees' actual situation. She says that, in general, Palauans are very caring - and eventually, they will open their hearts to the Uighurs. "But people living on a small island," Lomongo says, "they hear something that's negative and they believe it."

Pastor McClure, fresh from his morning service, acknowledges that Palau is a very accepting society. He doesn't know the men's background or why they were arrested. But he says there are fears that Palau might inherit some of the problems of religious violence that plague other countries in the region. McClure mentions his own experience travelling in the Philippines, located some 500 miles from Palau and home to an active Muslim separatist movement. The streets were littered with barricades, and the military stopped every car at checkpoints to search for weapons. "It is something that I don't want to see happen here," he stresses.

At the same time, the pastor says he understands that the president of Palau needed to take the money. "The president is trying to prevent his economy from failing," says McClure. Perhaps the $200 million in aid is not a bribe, he says, but rather "a gift, but one with strings attached." The good thing, he points out, is that there is "nothing to blow up here. If they get into trouble, they can't really go anywhere. Only to jail."

What is important now is to prepare for the Uighurs' arrival and make them welcome, he says. "If they are guilty," says McClure, "they will be allowed penance." With the rain still falling hard, the pastor looks across his congregation, noting that some among his own flock have been in trouble with the law in the past but have since reformed. "Palau is a place to find a new beginning," he says, "a place for a new start."

Martha Ann Overland, a reporter based in Hanoi, writes for Time, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and numerous other publications.