Nothing is more quintessentially Arab than a camel train passing slowly through a landscape of rolling sand dunes.

For thousands of years the dromedary was an essential companion to the Bedouin thanks to its ability to endure the most extreme hardships of desert life.

But now the value of prize camels is leading to astonishing advances in veterinary science in the UAE, as owners look to make money from their beasts.

Cloning and embryo transfer are resulting in camels that run faster, produce more milk, or are more likely to catch the eye of a judge in a beauty contest.

The science was pioneered by the Camel Reproduction Centre, off the Dubai-Hatta road. It was set up more than three decades ago by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, Vice President and Ruler of Dubai.

Injaz, celebrated as the world’s first cloned camel, was created at the CRC in 2009 and lived for more than a decade.

She resulted from work by Dr Nisar Wani, who now works as scientific director at the Reproductive Biology Centre.

The expensive cloning process is now used for the most elite racing camels, among others.

“Currently we cater to the demand of UAE clients. But there is a huge demand from other Gulf countries as well,” said Dr Wani, who is from India.

"As camels are seasonal breeders, we can work on them only during this season, which is usually from October to March each year."

Cloning has captured the public imagination since Dolly the sheep came on the scene 25 years ago at the Roslin Institute in the UK.

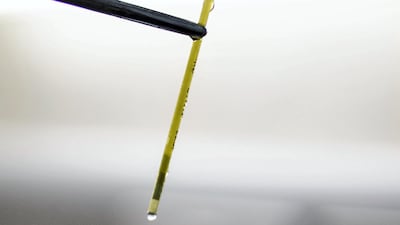

Using a similar technique, Dr Wani creates cloned prize camels through somatic cell nuclear transfer, where genetic material is taken from non-reproductive cells and transferred into a donor egg.

This is implanted into a surrogate camel for the 13-month pregnancy.

While it sounds simple, it is actually immensely complex and has a low success rate.

But it is also a powerful technique. Somatic cell material may be stored at low temperatures so that a creature can, in a sense, be brought back to life years after death.

As well as cloning dromedary camels, the Reproductive Biotechnology Centre cloned creatures such as the Bactrian (a double-humped camel) and also researched methods to genetically modify camels for desirable traits.

Despite the difficulties and the cost – reportedly as much as Dh200,000 ($54,500) – cloning is valued because it produces a genetic replica of the single parent.

Owners who pay for a copy of an animal known for its speed on the racetrack could enjoy rich financial rewards, because the offspring will be valuable and capable of winning big on the track.

“There is a continuous demand for this technique to reproduce elite animals like racing champions, prized breeding bulls, winners of beauty contests and high milk yielders,” Dr Wani said.

During each camel breeding season the Reproductive Biology Centre achieves dozens of pregnancies through cloning and more than 20 calves are typically produced. Each is, in a way, a genetic miracle.

How one camel couple can produce 15 calves in a year

Embryo transfer is a more popular, cheaper way to continue the hereditary line of a fast or particularly attractive camel, and many thousands of calves have been born at the Camel Reproduction Centre through this process.

It allows as many as 10 to 15 young camels to be produced in a season from a single cross, a stark contrast to traditional mating where the camel's gestation period slows things down.

“If you have a good donor animal – a good racing, milk or beauty camel – you’re talking about one calf or two calves at best every three years [without embryo transfer],” said Dr Lulu Skidmore, the CRC's British scientific director, who works with a Spanish senior researcher, Dr Clara Malo.

To produce several embryos, the chosen female camel is given hormones to stimulate the release of many eggs, and is mated with a high-end male, such as a top racing animal.

The resultant embryos – there may be 25 or more – are flushed from the female after about a week and transferred one at a time to surrogates, whose reproductive cycles are synchronised with the donor’s.

These “run-of-the-mill” camels carry and give birth to the young.

Success rates for embryo transfer are now as high as 65 per cent to 70 per cent, but that reflects decades of accumulated expertise.

Centres such as the CRC had to develop procedures for embryo transfer in camels themselves, because the process for horses could not be transferred wholesale.

The Veterinary Research Centre, a leading scientific centre in Abu Dhabi, also created thousands of these camel calves over the past three decades.

The popularity of the technique is understandable, not least because of its ability to create large numbers of camels with impeccable racing pedigrees.

Dr Skidmore, who holds a doctorate in camel reproduction from the University of Cambridge, said "the money is in racing".

“If they’re a valuable camel, their calves are going to be worth a lot of money. They will run races and win cars and all sorts of other fancy things,” she said.

The centre may deal with as many as 300 camels owned by clients each year, but demand is such that more labs are being set up to do embryo transfer.

However, the technique, which is non-surgical and does not require the animal to have a general anaesthetic, costs up to Dh20,000 when top quality animals are used.

The calves that result may be worth hundreds of thousands of dirhams.

The CRC also produced camels from frozen sperm, identical twins have been born through embryo splitting and Dr Malo has worked on IVF in the creatures.

"It's getting a lot more interesting. A lot more owners are getting familiar with procedures such as embryo transfer," Dr Skidmore said.

“They realise the benefits of producing more of the best racing camels. The same technique can be used for milking camels.”

So the brave new worlds of embryo transfer and camel cloning – and of other high-tech methods to produce top-quality dromedaries – is here to stay.