It had been a long voyage from damp, grey Hartlepool on England’s North Sea coast, through the Suez Canal and Red Sea until finally rounding the Strait of Hormuz.

Now the Nigaristan, one of a fleet of cargo steamers owned by the Strick Line and named after Persian provinces, rocked gently at anchor a little way off the beach at Abu Dhabi.

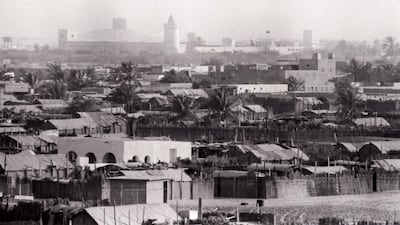

Viewed from her decks, the town buzzed with energy and new construction in anticipation of the coming oil boom. There was no port yet, so pontoon barges pulled along the ship, collecting the cargo and delivering it on to the sand.

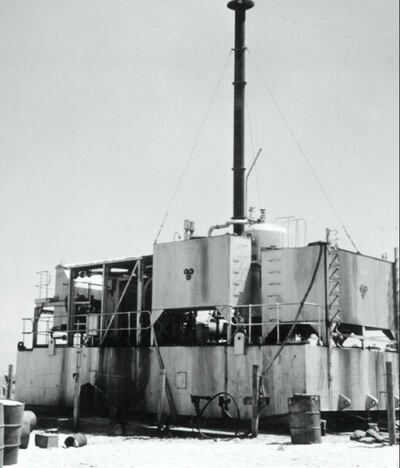

They sat there, a collection of wooden crates whose contents were eventually assembled into a device no one had seen before, a massive rectangle of machinery with a tall chimney and pipes that ended in the sea.

It was 1961, and Abu Dhabi was about to get its first taste of fresh drinking water.

Just about.

The desalination plant had been ordered by Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan, Ruler of Abu Dhabi, from Richardson & Westgarth and was one of the first of its kind. But what worked well in West Hartlepool did less so in the conditions of an Arabian Gulf summer.

For starters it did not function above 26°C. It was also technically complicated and required constant maintenance.

To improve output, the Ruler ordered a second machine, this time from a supplier in Kuwait. The Bennis Thermoflash was reported to have cost £200,000, the equivalent of over Dh18 million today, but was missing several vital components, including storage tanks, for which another £27,000 was demanded.

As Sheikh Shakhbut and the supplier argued over the contract, the Thermoflash sat idle on the sand.

Still, it was better than what had gone on before. For decades, the people of Abu Dhabi obtained their water by digging pits in the sand. The liquid at the bottom was brackish and barely drinkable. After a few days it was fit only for animals and then washing. So another pit would be dug.

As the Emirate prepared to export its first oil in 1962, workers began to flock to Abu Dhabi from all over the world. Offices, banks and apartment blocks began to spring up around old arish palm fronds and coral houses. Even the alternative to pits, importing water in barrels from Dubai, was no longer enough.

Desalination at least offered a solution. By the time it was working properly, by September 1962, the Richardson & Westgarth plant was producing 50,000 litres of fresh water a day.

It was collected in metal cans and distributed across the town by a network of donkey carriers, sold at the equivalent of a dirham per gallon, or 4.55 litres, at a time when the market price of gallon of crude oil was 70 fils.

The previous decade had been driven by the hunt for two precious liquids that would determine the future of what is now the UAE. One was oil. The other was water.

The seven emirates would thrive with the first. But they would die without the second. And so providing a plentiful supply of fresh, clean drinking water became a priority.

Water could be found in what was then called the Trucial States, but from the perspective of economic development it was mostly in the wrong place; deep inside the mountains of the Northern Emirates and around Al Ain, then a collection of villages known as Buraimi.

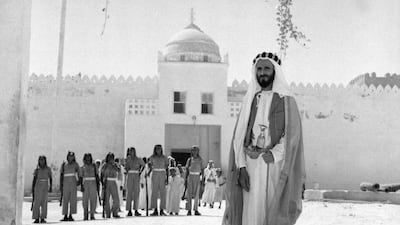

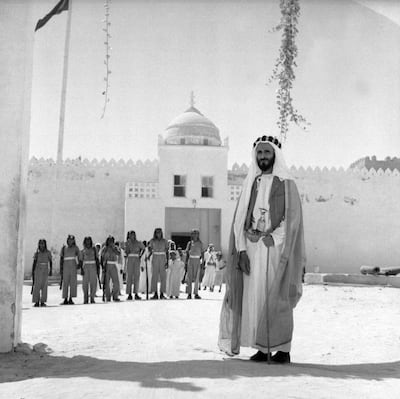

It was here that Sheikh Zayed, appointed governor of the Eastern Region by his brother Sheikh Shakhbutin 1946, made improving the water supply one of his first acts.

The ancient falaj, man-made channels that carried water from underground sources to irrigate crops and supply the inhabitants, were cleared and restored on Sheikh Zayed’s orders.

By the mid 1950s, Britain was supplying Sheikh Zayed with money and resources to expand them further.

“The improvement to the falajes, which have resulted in a spectacular increase in the flow of water to the gardens in Buraimi, have impressed the inhabitants, more than anything else we have done,” the Political Agent Peter Tripp reported in 1956.

More remarkable than the flow of water, was London’s sudden interest the welfare of the people of the emirates. Overlords of the Arabian Gulf for more than a century, Britain’s sole concern had been to pacify and protect the sea routes to its Indian Empire.

During the 19th century the British had imposed a series of treaties, or “truces”, that effectively gave them full control of the emirates’ dealings with the rest of the world. Internally, they would interfere only if they felt the stability of the region was threatened.

So why the sudden interest in water supplies? With India and Pakistan’s independence in 1948, Britain’s priorities for the Gulf had changed. The focus was now on oil and gas, vital to the UK economy.

Into this mix came the rise of Arab nationalism. The Suez Crisis of 1956 ended in humiliation for Britain and France, as Egypt’s charismatic new leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser led the call for Arab people to cast aside their imperial bonds.

So concerned was London about the influence of Cairo in the Gulf that a letter was sent to the British Embassy in Khartoum that year asking for help in recruiting Sudanese for a variety of posts from engineers to schoolteachers “as a more desirable source of supply than Egypt.”

Clearly if Britain wanted to keep Arab nationalism out of the Gulf it would have to do more for the local population than act as the policeman.

A first step was the Trucial States Development Fund, with a five year modernisation plan announced in 1955 and a budget of £450,000, worth around £12 million today or Dh57.7 million.

Policing, education and health were the priority, but it was clean water that was the most complex problem to solve.

Drilling equipment was ordered from Britain, along with workers to operate it, and shipped to Dubai in late 1954. The 1955 budget was set at £25,000 (£660,000 today) and included two windmills, improvements to Al Ain's falaj system, but with over half allocated for well drilling.

Records show that Sheikh Zayed was increasingly anxious to see a better life for his people. After a meeting with the UK representative in July 1958, the Political Agent sent an urgent message to London marked “confidential”, warning of “growing pressure from the more progressive elements in the area.”

By the start of the 1960s, the five year plan was showing results. Drilling had produced enough wells to supply Dubai and the Northern Emirates with clean water, including Sharjah.

For Dubai, this involved a 40 kilometre pipeline from the well at Al Aweer, to the west of the city which began operating in 1960, with the first water piped directly into homes and offices beginning in 1965.

Abu Dhabi, though, remained a problem. There was literally not enough water for the growing town. Unusual, even eccentric, alternatives were considered.

A diviner was hired, using a technique called dowsing that claims to discover water underground using “earth vibrations” that make a wooden rod twitch when held over the source.

Col Kenneth Merrylees duly wandered across the island and surrounding areas, but despite what he believed would be a £100,000 reward for success - nearly Dh2 million in today’s prices - his rod did not detect any water.

The good news, the colonel told the Ruler, was that he believed he had discovered two more oil fields nearby. The response, as noted in a British report from 1962, was “(Sheikh) Shakhbut said that he had enough oil for the time being.”

That left the desalination plants as the sole source of Abu Dhabi water. A more radical plan was implemented, with a 128-kilometre concrete pipeline laid from new wells drilled outside Al Ain directly to a massive water storage tank in Khalidiya.

Water began to flow from Al Ain in 1965, with the systems capacity estimated at 400,000 gallons a day – almost ten times the existing supply.

In the end, though, it was improvements in desalination technology that would solve Abu Dhabi’s water problems. The huge candy striped towers of the city’s plants that can be seen from the Sheikh Zayed Bridge today are a far cry from the those that sat in the beach in 1962.

Although no longer in use, the water tank in Khalidiya survives. It can be seen, sitting on a low hill in a residential area just behind Khaleej Al Arabi Street; a reminder of a time when a bottle of spring water was not so much a fashion accessory but more a matter of life and death.