The young Trucial Oman Scouts soldier rushed to his squadron commander with some surprising and unexpected news.

Out of the blue, two Americans had turned up at the fort.

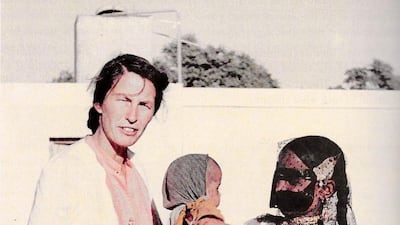

Pat and Marian Kennedy were a married couple and both doctors. Suitcases in hand, their arrival meant Al Ain, and the emirate of Abu Dhabi finally had its first medical service.

That was 60 years ago, with the pioneering efforts of the Kennedys honoured last month by the renaming of the medical centre they founded.

Oasis Hospital became Kanad Hospital, in recognition of how the local population pronounced their surname.

"They arrived with nothing, they couldn't speak any Arabic at all," Anthony Rundell recalls of his first encounter with the Kennedys in 1960, speaking to The National at his home in London.

“They didn’t have anywhere to live and no medical facilities at all.”

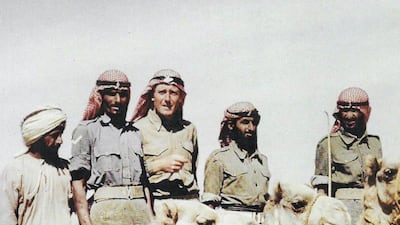

Now long retired from active service, Mr Rundell was a British officer with the Scouts and one of the few people still living who can recall the couple’s arrival and a turning point in the Emirate’s history.

He joined the Trucial Oman Scouts after serving in the British Army in Malaya and, still in his early 20s, led a squadron of Arab soldiers, some of them local.

It was their job to keep order from the base at Al Jahili fort, now part of Al Ain city, but then part of a collection of villages surrounded by mountains and empty desert.

The arrival of the Kennedys, with their children in tow, was a bit of shock. Not just because there was no warning, but because he had been the only Westerner for hundreds of kilometres.

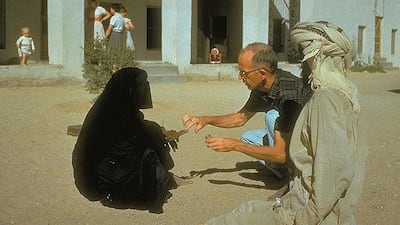

It was also obvious their skills were desperately needed. A lone doctor made occasional visits from Abu Dhabi, and the squadron had a orderly with rudimentary first aid skills but beyond a few aspirins, there was little treatment available for those who fell sick.

The result was incredible hardship. It is estimated that up to half of all Emirati infants and a third of mothers died during childbirth, or of later complications. That was at a time when the mortality rate in the West was about around three per cent.

Blindness and glaucoma caused by the blowing sand was common among the desert tribes, with the only treatment folk remedies, like wrapping fever victims in the skin of an animal.

Mr Rundell had seen some of this this first hand, especially from his men, several of whom had wives living locally.

“Our soldiers used to complain because their womenfolk were lying in the sand bleeding,” he says.

The Kennedys had come at invitation of Sheikh Zayed, then the Ruler’s Representative in the Eastern Region, who was determined to improve the lives and health of his people.

The Kennedys were Christians, although it had been made clear to them there should be no attempt to convert the Muslim population. But in any case, says Mr Rundell, that was not their motive for coming.

“That was their mission; service to God,” he says.

“They were just good people. It sounds trite but I can't put it any other way. They just wanted to alleviate suffering.”

The presence of the scouts meant Mr Rundell could at least offer some practical support.

“Because I was running things I felt vaguely responsible for them,” he says.

His men built the simple arish palm frond hut that was the first consulting room, where the patients sat on the ground. An Arab soldier with basic English acted as translator between the Kennedys and Emiratis.

For other patients, especially women, it was a case of making house calls, sometimes in the villages but also in desert communities. Women initially refused to be seen by a male doctor, but were eventually won round by the work of Dr Marion Kennedy.

“She was a sharp woman, and I mean that in a nice way,” says Mr Rundell.

“Mrs Kennedy broke through the glass barrier and in the end Mrs Kennedy could do more or less what she could do.”

Until the Kennedys arrived, the wombs of women were routinely packed with salt to make them contract, while female genital mutilation was also widespread - two practices which Mrs Kennedy was determined to stamp out.

At the same time, the couple were not thrown by the conditions they encountered.

“They wouldn’t be shocked by anything; they absolutely weren’t like that," Mr Rundell says.

”They were completely level headed, just committed to what they were doing without being ostentatious at all. They were just humble people who had this calling from God to do this work.”

Within months, the improvement of the health of the local community was becoming obvious,” says Mr Rundell, who later became Sheikh Zayed’s desert intelligence officer until leaving the Scouts in 1962. The Kennedys continued their work in the UAE until the mid-1970s, when they moved into private practice in northern California.

Pat Kennedy died in 2000 at the age of 81. Marian Kennedy passed away in 2008 at the age of 84 in Carmichael, near Sacramento.

The simple palm frond hut eventually became a sophisticated hospital that now serves over half a million people. Tens of thousands of babies have been born there, including Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, and Sheikh Saif bin Zayed, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Interior. Infant mortality in the Emirates is now less than one per cent.

All this was the vision of Sheikh Zayed to improve the lives of his people.

He started it all,” says Mr Rundell. “He got all this done. It was the start of a revolution - with the easing of pain.”