It was the second week of May 1973 and, under conditions of absolute secrecy, a heavily guarded convoy of lorries wound out of Dubai International Airport.

Driving steadily west, the convoy picked up speed as it reached the empty desert of Jumeirah and crossed the border to become some of the first vehicles to use the new single carriageway that connected Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Several hours later they reached their destination, the National Bank of Abu Dhabi. Printed in London, then flown more than 4,800km to a country not yet two years old, here, in tightly packed bricks of paper, was the wealth of a nation.

Or at least its banknotes. It is 50 years since the UAE dirham made its debut and the now familiar coins and notes became the official currency.

Quickly put into circulation

The news of the new currency had been made public only a week before it became legal tender on May 19, 1973.

It was revealed on the May 12 front page of Abu Dhabi News, the English language newspaper of the time, under the headline "New Currency for the UAE" and reporting: "The United Arab Emirates will have its own currency replacing the existing currency of Bahraini dinar and Qatar-Dubai riyal."

A fuller account came a week later in the Gulf Mirror, which revealed: "The UAE currency arrived last week in Dubai on chartered planes in great secrecy."

“All banks in the UAE were closed yesterday through to Thursday while the National Bank will send the banks, all over the UAE, the necessary amounts of new currency for their current circulation,” the paper said.

It claimed the design of the dirham had not been without controversy; “There was a dispute over printing some verses from the Holy Quran on the new currency.

“It was argued in some circles that since the currency would circulate among non-believers, it was therefore against the principles of Islam to have such verses printed.”

A money of its own

Most people, though, were glad to see the back of a confusing jumble of currencies that had existed previously, in some cases for more than a century. A country that had come together on December 2, 1971 now had money it could call its own.

Mohan Jashanmal, whose family name is familiar on shops across the Arabian Gulf, recalls that Abu Dhabi was undergoing spectacular growth by the early 1970s, the result of expanded oil production and rising energy revenue.

“Everything was turned upside down. The Corniche was being built and there were new roads everywhere.”

It created a problem. “At that time we had to have shipments to get money into the country.”

In the case of Abu Dhabi, the money being brought in was the Bahraini dinar, adopted in 1965.

For Dubai, the official currency was the riyal, the result of the Qatar-Dubai Currency Agreement of March 21, 1966.

Before that, the currency situation was even more complex. From the 19th century, many traders in the region turned to the Maria Theresa thaler, from which the name dollar is derived.

Minted from silver and bearing the head of the Austrian empress, the coin carried only the date of her death in 1780.

So popular was this universal currency that versions were minted all over the world. The Birmingham Mint in England was still striking silver thalers for use in the Middle East as late as 1955.

'The Gulf rupee'

In 1945, a British official in the Gulf noted in his annual report to superiors that: “The Maria Theresa thaler, the local currency, appreciated steadily during the year …Prices of local product have all to be paid for in this currency and the poor, especially those on low rupee salaries, have accordingly suffered.”

A solution was the widespread adoption of the Indian rupee, but its popularity put an increasing strain on India’s currency reserves, and in 1959, the Gulf rupee was introduced, printed in red and pegged to the British pound at the rate of 13.5 to £1.

Another seismic change took place in 1966. India’s increasingly perilous finances led to the government of Indira Ghandi devaluing the rupee by a staggering 57 per cent on July 6. The Gulf rupee was not spared. Anyone holding the currency was instantly poorer. The currencies of Bahrain and Qatar provided a temporary fix.

Even after the creation of the UAE, the picture was still confused. Advertisements in the local newspapers, including those for government contracts, could be in any one of three currencies, including the rupee.

A single currency was essential if the new government was to retain monetary control. And so the dirham was created, an ancient name known from the early days of the Byzantine Empire and drawn from the Greek for “handful”.

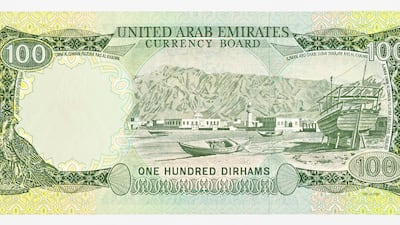

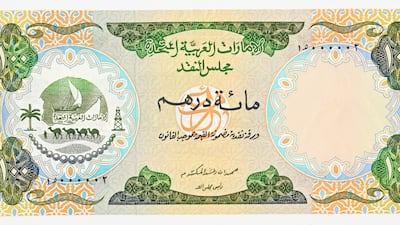

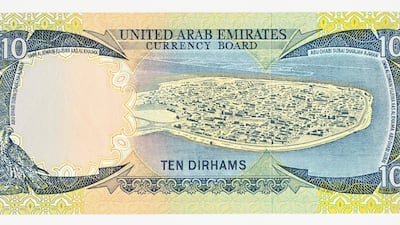

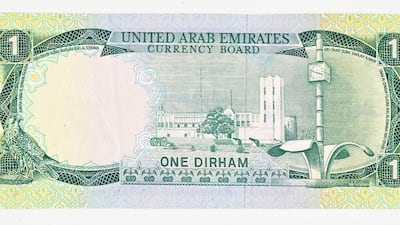

Dirham banknotes were printed in six denominations from Dh1,000 to Dh1 and embossed with local scenes and their value in Arabic and English.

The Dh1,000 note showed the Jahili Fort in Al Ain and the minaret of the Great Mosque in Dubai; the Dh1 was illustrated with the fort at Sharjah, then the police station, and the old clock tower. All carried the falcon watermark.

Coins were also minted, from a Dh1, slightly larger than the one in use today, down to a single fils, in bronze and featuring a stand of palm trees. Rarely seen these days, the coin is still technically in circulation, like its equally elusive bigger brothers, the five and 10 fils.

Mohan Jashanmal recalls the dirham arrived without any pain. Currencies in the region were valued against the US dollar, he points out, which made conversion easy. “We never had any riyal problems.”

In August 1973, the Currency Board took out newspaper advertising to warn the Qatar-Dubai riyal would cease to be legal tender by mid-September. In November, the Bahraini dinar followed suit. The mighty dirham now ruled over the UAE.

A version of this story was first published on May 17, 2018