For centuries, rumours swirled like a desert sandstorm of a city lost deep in the Empty Quarter of Arabia, half glimpsed but never quite reached, like a shimmering mirage.

Its name was Ubar, or Iram of the Pillars, once ruled by a tribe called the ‘Ad.

The Quran relates how the city was destroyed by God for abandoning the teachings of the Prophet Hud.

The Surah Al Fajir (The Dawn) asks “Hast thou not seen how thy Lord did with 'Ad, Iram of the Pillars, the like of which was never created in the land?"

It reveals: “Thy Lord unloosed upon them a scourge of chastisement; surely Thy Lord is ever on the watch.”

The story of Ubar, once fabulously wealthy and then destroyed, also appears in the tales of 1001 Arabian Nights, whose Arabic version is at least 1,000 years old.

In the translation by the 19th century British writer and explorer Sir Richard Burton, it is found by a man searching for a lost camel in the deserts of Al Yaman (Yemen) who comes across “a great city girt by a vast castle around which were palaces and pavilions that rose high into middle air”.

This, he later learns, is “Many-columned Iram,” the creation of “Shaddad, son of Ad, King of the world”. For his arrogance, Shaddad and his court are destroyed by God, who also obliterates the road to Iram, making it impossible to find.

In the 20th Century, serious efforts were made to discover the truth about Ubar. T E Lawrence, best known for his wartime exploits as Lawrence of Arabia, called it the “Atlantis of the Sands” and “a city of immeasurable wealth, destroyed by God for its arrogance, swallowed forever in the sands of the Rub al Khali desert“, but his proposal for an expedition was cut short by his death in a motorcycle accident in 1935.

Bertrand Thomas, a British diplomat and explorer, who was the first Westerner to cross the Rub’ al Khali or Empty Quarter, was at first convinced that Ubar was real when he encountered broad camel tracks near the desert’s southern edge.

As he recounted in his 1932 book of the expedition Arabia Felix, his Bedouin guides told him “There is the road to Ubar”, describing it as “a great city, our fathers have told us, that existed of old, rich in treasure, with date gardens and fort of red silver”.

Another British explorer, and advisor to Ibn Saud, Ruler of Saudi Arabia, was Harry St John Philby, who made another crossing of the Rub’ al Khali in the winter of 1932 and ’33.

Philby was also intrigued by Ubar, writing that: “There can be little or no doubt that the legendary city of the sands…is one and not many.”

Both Thomas and Philby eventually decided that Ubar never existed, with Philby writing: “So far as the Rub’ al Khali is concerned, it is a myth and no more.”

Hope remains for elusive discovery

The story, however, did not go away. In 1944, a Royal Air Force Lodestar transport plane, flying from Salalah, on the southern coast of Oman, to Muscat, became lost over Arabia.

Heading north, he found himself over the Empty Quarter, before, nearly out of fuel, landing at the RAF base in Sharjah.

There he told a story of seeing an abandoned city, hidden on the summit of a flat topped mountain, or mesa. Dropping to a lower altitude, the pilot saw large fortress-like structures and ruining buildings, but no sign of life.

That, at least, is the version retold by Raymond O’Shea, an airman at the base, who later published an account of his time in Sharjah, The Sand Kings Of Oman.

Fired up by the airman’s story, O’Shea used two weeks' leave to find the city, using the pilot’s co-ordinates and hiring local guides. It was not difficult. The site was just a few days into the desert from Liwa Oasis.

There, O’Shea, and a companion called Schultz, discovered the city exactly as described. Climbing to the summit of the hill he found two acres of crumbling sandstone ruins.

“Most of the buildings were a mass of rubble, so that it was difficult to distinguish houses or streets, but two of the towers were still standing; these measured 30 feet in circumference and 40 feet high… The walls themselves were in places four feet thick, the stone blocks ― the largest of which measured two feet in length and 18 inches in width ― being held together by a rough mortar made of gypsum and clay.”

Realising he was running out of water, and that Saudi Arabia was out of bounds for members of the British armed forces, he stayed only a few hours before returning to Sharjah.

O’Shea’s book was published in 1947, with a map triumphantly marking his discovery of “the lost city of ‘Ab”. It is fair to say it was not well received.

His description of Sharjah led to a complaint by the Ruler, while British officials called it “derogatory” and “full of the most appalling inaccuracies”.

More problematic was his “discovery” of the lost city. No rock formation resembling his hilltop could be found anywhere near his claimed location. Worse, a series of photographs of Ubar were quickly exposed as buildings in Muscat. Among the many critics was the explorer Wilfred Thesiger, who had recently completed his own crossing of the Empty Quarter.

A secret buried in the sands of time

O’Shea is not completely discredited. It Is possible he was mistaken about the location, while the Muscat photos had been the choice of his publisher, looking to add local colour.

In any event, Ubar remains as lost as it had ever been. Then, in 1982, an American documentary maker, Nicholas Clapp, began another search.

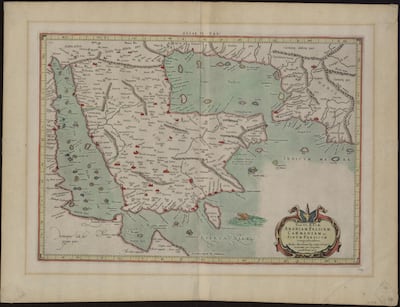

Clapp began looking not among the sands of the Rub al Khali, but in the University of California in Los Angeles. He suspected the real Ubar might be a city called Omanum Emporium, plotted on Ptolomy’s famous Second Century map of Arabia.

Omanum Emporium - the Latin for Omani Market- would have been a major trading stop on the incense caravan route from Arabia to the markets of Jerusalem, Damascus and Rome.

Next he turned to Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Lab with an audacious proposal to use a ground penetration radar on the Space Shuttle to detect ancient camel tracks long invisible to the human eye.

Nasa agreed, with the search eventually focusing on an oasis site called Shisur. This was not exactly a new discovery. Shisur, or Shisr, had been visited by American oil prospectors in the 1950s, who had also briefly looked for a lost city, but found nothing.

Both Thomas and Thesiger knew of the site, but believed it was only a few hundred years old.

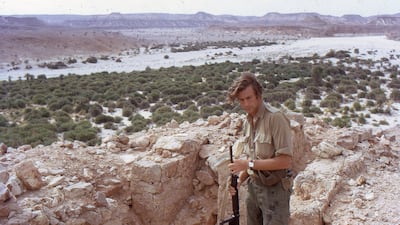

Clapp thought there might be something more, and, in 1990, began to assemble an expedition that included Sir Ranulph Fiennes.

Arriving at Shisur they discovered there was more to the site than meets the eye. Below the ruins of fort, they found evidence of more extensive structures including walls and towers. Pottery fragments at least 2,000 years old dated the site.

This version of Ubar had not been destroyed by the wrath of God. Built over an underground cavern, the weight of the walls had created a giant sinkhole into which everything had collapsed.

Case closed? Clapp certainly believed so. So does the tourist board, which has place a sign proclaiming “Welcome to Ubar. Lost City of Bedouin Legend.”

Questions — and doubts ― still remain. Even at its height, the settlement at Shisur was not much more than a trading post, with a population likely to have been less than 200.

This is far from the “palaces and pavilions” that were “rich in treasure” of myth and legend. Perhaps Ubar, city of pillars, destroyed by God for its wickedness, is still to be discovered under the sands of the Empty Quarter.

Perhaps also, it is the nature of lost cities to remain forever undiscovered.