Their names are rightly celebrated for the part they played in helping the Founding Fathers build the country we know today as the United Arab Emirates.

Figures such as Adnan Pachachi, the adviser to UAE Founding Father, the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, who became the first UN ambassador, Dr Abdul Makhlouf, architect of the modern city of Abu Dhabi, and Zaki Nusseibeh, who has had a long and distinguished career as cultural adviser to two Presidents and Minister of State.

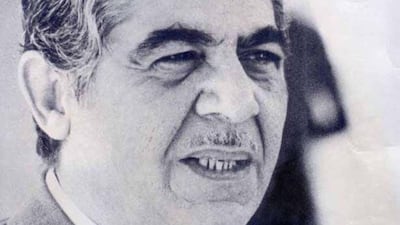

But what of Adi Bitar, whose work after more than 50 years, still shapes the daily lives of everyone who lives here?

The author of the Constitution of the UAE, the enormity of his achievement is perhaps concealed by the modesty of his personality, but also the result of a life cut tragically short.

Even for group photographs, “my father would just walk away”, his son Omar Al Bitar says.

“He was a modest man and not the type of person to boast about what he had done. Even when other people took credit for his work, he didn’t mind.”

Yet thanks to Bitar, the seven desert emirates, once ruled largely by tribal convention and cultural traditions, became a modern nation of laws.

In the words that he penned, “Equality, social justice, safety, security and equal opportunities for all citizens shall be the pillars of the society.”

Yet he barely saw the UAE beyond its birth in 1971, dying of cancer just two years later at the age of 48. He is buried beside his 10-year-old son, Issa, struck down by leukaemia only three months earlier.

Early life and escape from Zionist bombing

Bitar was born in Jerusalem, on December 7, 1924. His father, Nasib Al Bitar, was a distinguished judge who had studied at Cairo’s Al Azar University and later served in the First World War as an officer in the Ottoman Empire, of which Palestine was then a region.

By the time of Bitar’s birth, Jerusalem was under the control of the British Mandate, and he was educated first at the multi-denominational Terra Sancta School and then at the Palestinian Institute of Law where he graduated with honours in 1942.

By then tensions were growing between the British authorities, Palestinian Arabs and Jewish settlers, whose number was increasing rapidly as they fled the aftermath of Hitler’s Germany at the end of the Second World War.

By now Bitar was gaining experience as a legal clerk and on the morning of July 22, 1946 found himself at the British administrative headquarters at the King David Hotel, overlooking Jerusalem’s Old City.

At 12.37pm, the Zionist terrorist group, Irgun, detonated a massive bomb in the hotel’s basement. Bitar escaped the blast largely unscathed, but as he went back into the building to rescue the injured, a large part of the south wing collapsed, burying him alive.

Most were convinced he had been killed, but Bitar’s brother insisted otherwise. Eventually Bitar was dug out alive but with serious injuries, including broken bones. He lived only because a table had sheltered him from the worst of the falling rubble.

Two years later the British Mandate was over, and the State of Israel declared. In the war that followed, Jerusalem’s Old City and the entire West Bank came under Jordanian control, and it was as a citizen of Jordan that Bitar gained his reputation as a lawyer.

His quick mind and keen intelligence lead to a senior appointment at the Attorney General’s office, where he worked until 1956. An appointment to Sudan followed, as a district judge, returning to Jerusalem three years later to set up a law practice.

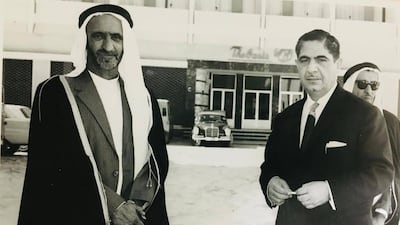

Bitar’s life changed forever in 1964. Working for Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the Ruler of Dubai, the British political agent for the Arabian Gulf approached the Jordanians.

They were looking for a legal adviser to the government of Dubai who could develop a framework of laws that would help the emirate’s development to a modern economy, including a civil legal system and courts.

Bitar’s name was put forward and accepted. He moved to Dubai and immediately set to work on laws and regulations that would govern everything from the banking system to the new Dubai International Airport, Port Rashid, the establishment of Jebel Ali, and even the decree that switched driving to the right-hand side of the road.

In 1965 Bitar was appointed Secretary General and legal adviser to the Trucial States Council, a forum at which the Rulers of the seven emirates would meet to discuss areas of mutual interest.

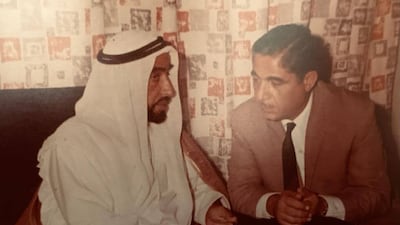

The post allowed other Rulers to know Bitar better, especially Sheikh Zayed, then Ruler of Abu Dhabi, and with Sheikh Rashid the major player in plans to create the Union of Arab Emirates.

The deciding moment came in February 1968, with a meeting between Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Rashid in the desert at Seih Al Sedira, on the border of Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

A decision was made to create a new country from the seven emirates, and with it a number of practical decisions, including the pressing need to draft a constitution.

Bitar, a familiar and well-liked figure, was the obvious choice.

He worked long hours to complete the task, from his offices at the Government of Dubai and Trucial States Council, then later in the day from the quiet of his home in Dubai, using the dining room table.

His son, Omar, would act as his father’s driver and assistant during this time, and remembers taking pages to be typed and then copied on a mimeograph machine, the precursor of photocopiers.

The finished document, with 152 articles, and in the words of the Government “establishing the basis of the UAE and the rights of citizens in ten areas” was completed in time for December 2, 1971.

Some elements were intended to be temporary, including Abu Dhabi as the capital, with provision for a new city at Karama on the Dubai border, but this was abandoned and the constitution finally made permanent in May, 1996.

For Bitar, the future seemed to be continuing his distinguish career in the service of the UAE as a senior adviser both to the UAE cabinet and the Prime Minister, at that time Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid. It was not to be.

His youngest son, Issa, was diagnosed with leukaemia, with treatment in Lebanon, the UK and Dubai. It was during this period that Bitar told his family he needed to visit Britain, on a working trip to discuss the printing of UAE passports.

In fact Bitar was also unwell. In London, he arranged to see a consultant and was diagnosed with stage 4 liver cancer. At one point the treatment, at the American Hospital in Beirut and in Dubai, seemed to be achieving some results, but in January 1973, Issa died, his father at his side. He was 10.

Issa’s death seemed to break Bitar. His own health declined rapidly, and in March 1973 he also died, to be buried by his son’s side.

His wife and surviving children remained in the UAE, becoming citizens of the country Bitar had helped to create.

Of his surviving sons, Nasib, who died in 2011, was a documentary writer and senior figure at Dubai Television, where he was director of programming, and creator of Alarabiya Productions, where he created the series The Last Cavalier.

Omar Al Bitar rose to become a major general in the UAE Armed Forces, vice president of the Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, then ambassador to China and vice president of the Emirates Diplomatic Academy.

Of his father, he says: “He was a man of vision, a man of ethics. He would discuss with you any matter. He had a depth of knowledge. He was a man of calibre and integrity.”