Returning to the UAE in 1990 to become Britain’s ambassador, Graham Burton must have felt it was a homecoming.

His long relationship with the country and the region began more than 25 years earlier when he arrived in Abu Dhabi in 1964 as a junior official with what was then known as the political agency.

Burton, who died aged 80 earlier this year, was far from typical of the British diplomats of that time.

The son of a civil servant and educated at a state school, he studied law at what would have been described a “red brick university” rather than the private school education of many of his upper class peers.

He later recalled with some pleasure trying to make small talk with his boss, Hugh Boustead, a decorated war veteran whose own father had been director of the Imperial Ethiopian Rubber Company.

Boustead admitted he had never heard of Burton’s school, and showed confusion that not only had the new boy never attended Oxford or Cambridge but that he could not even ski.

Burton’s good nature and sensitivity to local values soon overcame any differences, with Boustead increasingly depending on his young assistant, summoning him to his office, in the absence of telephones, with three blasts on a whistle.

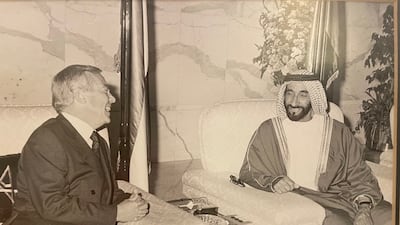

Burton remained in Abu Dhabi until 1966, leaving after the transition that saw Sheikh Zayed replace his brother, Sheikh Shakhbout, as Ruler.

Now married, his next stop was Lebanon to study Arabic at the Middle East Centre for Arab Studies, regarded by some as a training ground for British spies.

For Burton, it was a chance to develop his linguistic skills, which he did in part by playing backgammon with the local garage owner, with the next stop in his career a posting to Kuwait in 1969 as commercial officer.

After returning to London to the Middle East department of the Foreign Office, he headed to Uganda in 1975 for a temporary post during the turbulent rule of Idi Amin that saw him persuade the president to commute the death sentence on a British academic who had written an unflattering book.

Next was Tunisia as deputy head of mission, then, in 1978, New York, as Middle East specialist at the UK mission to the UN. Four years later, he moved to Libya as counsellor at the British embassy.

British officials left Tripoli in 1984 after British policewoman Yvonne Fletcher was murdered by shots fired from inside the Libyan embassy in London. Burton's next post was to co-ordinate security inside the UK Foreign Office, a sensitive and complex task that led to him being knighted in 1987.

He returned to Abu Dhabi in 1990, this time as ambassador, welcomed by those who remembered him as an honourable man. According to his obituary in The Times of London, “a characteristic of his approach was the attention he paid to the British community". The paper said: "He always said that members of the community would know someone local better than he did and were a valuable source of advice."

When he left the UAE in 1994, Burton became ambassador to Indonesia before a final posting as UK high commissioner to Nigeria.

In retirement he supported the Sightsavers charity and later worked as a volunteer porter at a London hospital. He is survived by his wife, Julia and a son and daughter.