Emiratis have been urged to voluntarily give an anonymous blood sample to help expand data collection for the Emirati Genome Programme.

The project, launched last year, has so far collected blood samples and DNA cheek swabs from tens of thousands of citizens.

Genome sequencing can help in the diagnosis of conditions caused by changes in the DNA.

Researchers said the end goal is to collect samples from all of the Emirati population – about one million people – but as a voluntary programme.

Emirati nationals should be proactive in submitting their DNA for analysis, said officials.

"The purpose of the programme is to use genome data to further enhance health care in the UAE, with a focus on hereditary conditions," Dr Walid Zaher, chief research officer at G42 Healthcare, told The National.

“So far we have collected tens of thousands of samples, and that number is rapidly increasing as we speak.

“The aim of genomics is to translate biological data into usable data that can be analysed to change sick care into health care," Dr Zaher said.

“When you know what diseases and conditions are common and uncommon in populations, you can reshape your healthcare offerings.”

Dr Zaher, a lead researcher of the programme, said the target is to "achieve a fully sequenced population, not just a sample population".

No end date has been set for the full sample collection, but Dr Zaher said researchers want it done in the "least amount of time".

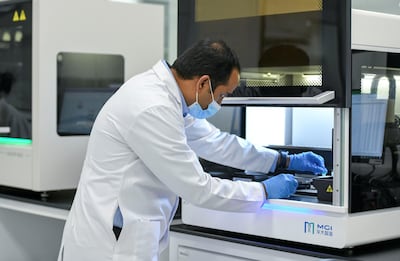

Teams at the Omics laboratory, run by G42 Healthcare, have already created the first reference genome from more than 1,000 volunteers.

Dr Zaher said the samples were still being analysed, so was unable to share any outcomes.

What is population genomics?

Population genomics refers to a new concept in terms of an individual's or a population's ancestry.

In humans, Dr Zaher said population genomics typically refers to applying technology in the quest to understand how genes contribute to our health and well-being.

Using biotechnology and artificial intelligence, researchers can characterise things like genetic variation and understand how they relate to different diseases.

The more samples a laboratory can get, the more data it has to work with, which in turn allows researchers to map out a clearer picture of how the Emirati genome operates.

How to submit a sample

“For people who may not know about the programme or may be hesitant to give a sample, it is a fairly non-invasive and anonymous process,” Dr Zaher said.

“Participants give a blood sample or buccal swab from inside the mouth, at one of the participating medical collection facilities.

“An Emirates ID is needed for verification and to sign a consent form and log details such as gender and age.

“At this time a barcode of the sample will be generated with no personal data, it will be de-identified, then sent to the lab for sequencing so scientists can extract usable data from it,” Dr Zaher said.

In the next 10 to 15 years, the aim is to translate the findings into clinical actions and improve the five P’s in health care: proactive, preventive, predictive, personalised and precise.

Using the data, Dr Zaher said they can predict, and in some cases prevent, diseases. Patients can also be proactive in taking necessary measures before becoming carriers of a disease.

“For patients with particular diseases, like cancer, healthcare specialists can tailor treatment to fit an individual genome,” he said.

“We can get rid of the one-size-fits all approach and have a one-size-fits-me approach instead.”

Hereditary cancer accounts for approximately 10 per cent of cancer cases worldwide, and results from heritable mutations in specific genes.

The risk of inheriting a gene mutation increases sharply in the case of consanguineous marriages – marrying a blood relative.

According to research by the Centre for Arab Genomic Studies based in Dubai, between 21 and 28 per cent of all Emirati marriages are between cousins.

It seems, however, the answers to the problem of increasing genetic disorders need not mean abandoning tradition but rather embracing the application of genomics technology.