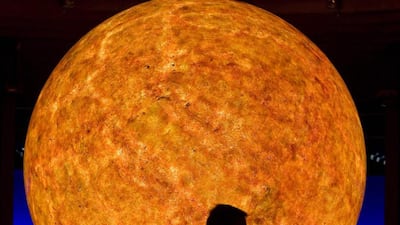

It’s the nearest thing we have to a perpetual motion machine: a huge incandescent ball that has been blasting out heat and light for 4.5 billion years. But now there’s mounting concern that there is something wrong with the sun.

Evidence is emerging that its thermonuclear furnace is misfiring. And that, in turn, is prompting fears we may be heading for climatic upheaval.

It has happened before, and now it looks set to happen again.

The most obvious clues can be found on the sun’s face. First recorded by Chinese astronomers more than 2,000 years ago, sunspots are now known to be linked to the magnetic field generated deep inside the sun. As such, they are indicators of the sun’s health — and, given its influence on the Earth’s climate, a bellwether of what might be in store for us.

The number of sunspots rise and fall on a more or less regular 11-year cycle. But the latest — Sunspot Cycle 24 — is on track to be the most feeble for at least a century, and possibly since records began.

Now scientists are taking seriously the possibility we may be heading towards a repeat of an event that last occurred more than 300 years ago.

Known as the Maunder Minimum, it is a period when low solar activity is followed by a long period of climatic upheaval.

In a study to be published later this year, and seen by The National, leading climate scientists in the UK state there is a significant risk of the Earth entering this “extreme scenario” within the next 40 years.

Their concern has been prompted by eerie parallels between current observations and events that occurred in the mid-1600s.

At the time, astronomers noted a marked decline in the number of sunspots — along with an outbreak of bitterly cold winters. This “coincidence” persisted for over half a century, until the sun started to resume its normal activity.

Exactly how the sun’s activity could have affected the Earth was unknown, and the issue remains one of the most controversial in science.

One of the biggest conundrums is that the most obvious idea — that sunspots reflect changes in the sun’s output — doesn’t seem to work.

Analysis of past sunspot cycles has revealed that the output of solar energy changes by barely 0.1 per cent between peaks and troughs. That, in turn, suggests that even if the sun is heading towards a Maunder Minimum, global surface temperatures would change by no more than about 0.2˚C. That is a small fraction of the temperature rise attributed to man-made global warming over the last 100 years.

But according to the authors of the new report, to appear in the prestigious Journal of Geophysical Research, there is a link; it is just more subtle than many suspected.

The researchers base their claim on computer models of a part of the atmosphere notorious for its bizarre behaviour: the stratosphere.

Lying about 10 to 50km up, this is where long-haul air passengers spend most of their journey time — along with the notorious jet streams. These ribbon-like bands of air travel at up to 400kph and act like barriers against the encroachment of bitter polar air into lower latitudes.

But depending on conditions in the stratosphere, the jet streams can weaken and meander off-course. This can allow polar air to creep closer to the equator, and warmer equatorial air to move closer to the poles.

The result is freakish weather, with neighbouring regions experiencing icy or mild conditions, depending on which side of the jet stream meander they lie.

Using the latest computer models of the stratosphere, the report’s authors have looked at how all this would play out during a Maunder Minimum.

And they found that — in contrast to the effect on ground temperatures — even a modest fall in solar energy could seriously disturb the stratosphere and its jet streams, with bizarre consequences.

The computer simulations suggest a Maunder Minimum would trigger a hefty 1.4˚C drop in the temperature of the stratosphere — more than 10 times that of ground temperatures.

This would also affect the jet streams, which would slow down and weaken. And that would lead to a higher risk of the meandering linked to freakish weather.

The researchers concede that their simulations are still preliminary and need refinement. Even so, the results provide the first clues to how falling sunspot numbers can foretell climatic upheaval on Earth.

Put simply, they signal a slight drop in solar output — one too small to affect global surface temperatures, but still big enough to disturb the stratosphere, and thus regional jet streams.

All this is bad news for anyone who likes a simple account of climate change. The record-breaking cold temperatures that gripped the US in the winter of 2013/14 were seized on by sceptics as proof that global warming is a myth.

At the time, scientists pointed out that it was actually the result of a jet stream meander, allowing Arctic air to move south — though the cause wasn’t clear.

The new research now casts some light on this. Global warming of the Earth’s surface is known to trigger a counterbalancing cooling in the stratosphere. The computer modelling has shown that this can also be accompanied by a warming of the lowest part of the stratosphere, making the jet stream less stable.

But the new research also casts doubt on the standard put-down to sceptics’ claims that the sun is a more plausible cause of climate change than human activity. Scientists have insisted that the changes in the sun’s output just aren’t big enough to affect the earth. The new research shows that while the effect on global surface temperatures may indeed be negligible, there can still be dramatic regional effects, due to the jet streams.

So where does this leave predictions about the future climate? Once upon a time, it seemed so clear: our addiction to fossil fuels would lead to increased greenhouse gases and thus a hotter planet.

But if the sun really is going off the boil, it looks like we should prepare ourselves for regular outbreaks of weather that just don’t follow the global warming script.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Reader in Science at Aston University, Birmingham