Researchers have uncovered the secrets of one of the UAE's largest and most diverse ecosystems.

The sprawling Khor Al Beida mangrove forest in Umm Al Quwain has been untouched by development.

Experts wanted to study it as a baseline to compare with mangrove forests that are closer to built-up areas to analyse how they were affected.

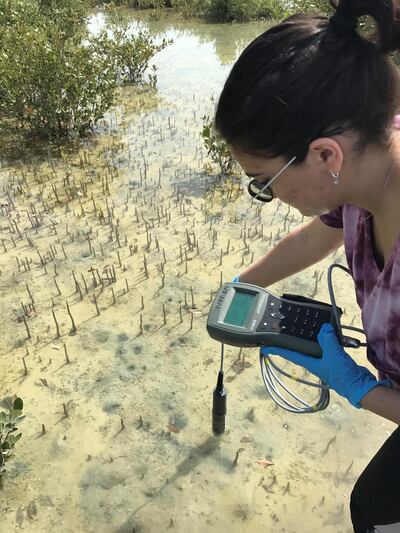

They studied the levels of trace metals in the water and sediment, as well as the presence of algae, which is the base of the sea’s food chain, to determine how healthy Khor Al Beida is.

Metals can find their way into water in various ways, said Dr Fatin Samara, associate professor of environmental sciences, at American University of Sharjah, who led the study.

Some come from vehicle emissions, while others are produced naturally by rocks.

Researchers did find trace levels of metals such as zinc in the water, as well as both aluminium and iron in sediments, but not at levels that would result in harm to the environment.

“When you find high amounts of heavy metals, it typically means there has been a lot of discharges, a lot of pollution nearby,” said Dr Samara.

“In most of the studies that I have done, usually I find high concentrations of pollutants. I was really surprised how undisturbed this ecosystem is.

“With the fast progress of the UAE and the speedy development, I was a little surprised.

“Although physically you can see there is not much around this area.”

In other good news, the team discovered the sediment in the forest was home to 53 algae groups, which was further evidence to suggest the ecosystem is healthy.

"They are sensitive to pollution, so their reduced abundance or diversity would have been an indicator of ecosystem disturbance," said Dr Nadia Solovieva Kettell, assistant professor at the Higher Colleges of Technology in Sharjah and University College London.

“Thankfully our study shows that the environmental status of the Khor Al Beida mangrove ecosystem could be considered undisturbed as shown by the healthy diversity of algae.”

Taken together, the low levels of metals and diverse algae suggest the forest was still in good health.

Dr Samara said the results show if steps are taken to protect mangroves from developments, they can still thrive.

“This suggests we can still develop, but we need to be careful with the development we do and we need to always have that environmental awareness in mind.”

Mangrove forests help protect the UAE coast from the effects of rising sea levels and storms, which are becoming more frequent owing to climate change.

They also act as a carbon reservoir, or sink, preventing carbon from entering the atmosphere, which is a major contributor to climate change.

Though much smaller in size than the planet's forests, these coastal systems sequester carbon at a much faster rate and can continue to store it for thousands of years.

The vast majority of the country’s mangroves are found in Abu Dhabi, which is home to the 19-square-kilometre Mangrove National Park. It constitutes 75 per cent of the total 4,000 hectares of mangroves in the UAE.

There are 13 major mangrove sites in the UAE.

A detailed study conducted by the Environment Agency Abu Dhabi in 2018 revealed that more than 80 per cent of the mangroves there were healthy, while 15 per cent were in moderate health and 5 per cent were identified as being in “deteriorating” health due to development.

The country undertook huge mangrove plantation programmes in the late 1970s under the directives of the late Sheikh Zayed, the UAE's Founding Father.

But between 2001 and 2011, some 20 square kilometres of mangroves alone were cleared to make room for coastal developments.

Thousands of mangrove trees have been planted since in an effort to rehabilitate many areas.

Last month, environment authorities announced they will use drones to plant new mangroves along the western coast of the emirate.

Environment Agency Abu Dhabi is working with Engie to rehabilitate the mangrove habitats near the French utility company's plant in Mirfa – about 90-minute drive west from the capital's city centre.