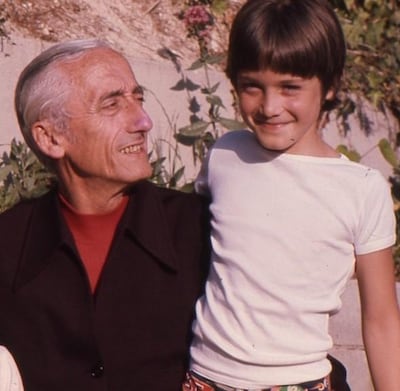

It’s not every boy who spends his formative years on board a former British Royal Navy minesweeper converted into a marine laboratory, but then few grew up as the grandson of an internationally renowned oceanographic researcher.

So it was that a young Fabien Cousteau would sit aboard RV Calypso while his grandfather, the biologist, explorer and conservationist Jacques Yves-Cousteau, explained the awe-inspiring biodiversity within the depths below and its significance to life on Earth.

"It helped me see the world from the bottom up in a way that highlights what makes our planet unique," Mr Cousteau, who first learnt to scuba dive on his fourth birthday, told The National.

As NASA was preparing to launch three members of the Expedition 63 crew some 250 miles to the International Space Station on a Soyuz spaceflight, Mr Cousteau described his ambition to create an equivalent facility for underwater research.

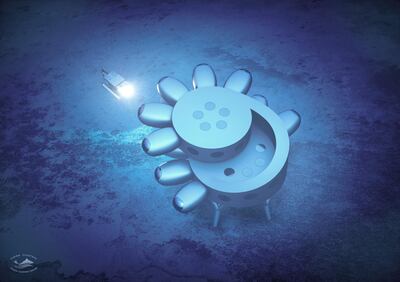

Named after the prophetic sea-god, the plan is for Proteus, a sort of international sea station, to sit 60ft below the ocean surface near the Dutch protectorate of Curacao. It is set to be the largest underwater research habitat ever made, located in a highly biodiverse, marine-protected part of the Caribbean.

When built, Proteus will be sustainably powered by hybrid sources, including wind, solar and Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC), and scientists hope to grow fresh plant life for food in its underwater greenhouse.

Although the design is yet to be finalised, the intention is for the station to be fitted with living quarters, a hydroponics lab, a submarine docking station, a medical bay and a video production studio, as well as state-of-the-art research laboratories. It will also provide full-spectrum light to ensure that the research team’s circadian rhythms are similar in the darkness at the bottom of the sea as they would be on land with sunlight.

Proteus partnerships

Mr Cousteau, now a marine biologist and ocean conservationist in his own right, aims to raise $130.4 million for the first iteration of Proteus. The project so far has financial backers from the Caribbean and the US but he is open to investment from other regions, including the Middle East.

Although the pandemic has slightly slowed progress, with funding in place he anticipates a 36-month turnaround from completed design and production of the station to its installation on the ocean bed. The first mission would then follow.

The 53-year-old’s longer-term plan is to build a network of underwater research hubs in different regions of the world’s oceans, to be able to stream big data in real time, 24/7, to help guide future climate-change policy on land.

“This brings opportunities on so many levels,” Mr Cousteau says. “Even if you're not a conservationist, I think that a smart business person or a smart government could see the value of having an underwater research station in their backyard.”

Proteus is a project of the Fabien Cousteau Ocean Learning Centre, a non-profit organisation founded by the aquanaut in 2016. It has strategic partnerships with major technology, data and submersibles companies, as well as with governments, though its founder says that politics should not play a role when deciding on collaborations.

Underwater International Space Station

“This is not a research station for creating weapons of war; this is more an International Space Station than a United Nations of the sea,” Mr Cousteau says.

There is currently only one active underwater research hub – the Aquarius Reef Base off Florida Keys in the US - but that was established back in 1986.

The aquanaut says the International Space Station and Proteus have many conceptual similarities. NASA and its Extreme Environment arm (NEEMO) missions use the Aquarius station for training purposes because it offers a comparable experience to being in space.

It is envisaged that Proteus, however, will provide 10 times the size of the living quarters of the International Space Station – also equivalent to 10 times the inner internal space of Aquarius. That and Proteus’s cutting-edge technology will make it an optimal training ground for future space missions.

Another similarity between Proteus and the International Space Station is their modular nature – both can add and subtract as many pods or sections as needed.

“And we cater to being as self-sufficient as possible so that we can follow in the steps of the International Space Station and deploy people for not days but weeks, months and maybe even longer.”

3D printed coral

The new station will enable scientists to study migratory habits of animals, as well as weather patterns, which Mr Cousteau says could help farmers optimise crop yields and society adapt to climate change. The technology on Proteus will also facilitate research into viral pandemics and a potential cure for cancer using chemical compositions of organisms such as deep-water sponges or fish-eating cone snails.

“We have another project in Curacao that we're going to start which is a coral restoration, involving research looking at 3D printing coral reef structures, inviting coral that's been evolutionarily accelerated in a natural process, so that it’s more capable of combating climate change,” he says.

Previous underwater research stations – such as Aquarius, Conshelf I, Hydrolab, Sealab – have accommodated up to six people. Proteus will hold as many 12, depending on how much space is deemed to give each scientist enough comfort to be able to work for long periods at a stretch.

Food for thought

“You need to be able to have the food systems that also cater to that because you burn as much as five times as many calories underwater as you do on land,” Mr Cousteau says.

He says that the duration of Proteus’s first mission would be bound by several parameters, including the toxic effect that can become a problem when crew members are exposed to prolonged high levels of oxygen.

Seven years ago, the scientist spent 31 days underwater inside Aquarius for Mission 31 with five others, the longest time clocked up by a team of six in such a station. “As much as 4,000 internal square feet sounds like a lot of space,” Mr Cousteau says.

“You're sharing it with 12 other people with all sorts of equipment, so you’re going to be in fairly close confinement, along with the psychological pressure of knowing that you're in isolation.

“I was more than happy to go another 31 days, but I'm an unusual person,” he says. “This is my backyard. This is home for me; I've done this my entire life.”

Mr Cousteau thinks that his late grandfather would be fascinated by Proteus. Jacques Cousteau’s team assembled several living and research stations in the 1960s, called ConShelf (Continental Shelf Station) I, II and III. He died in June 1997.

“My grandfather had visions of doing ConShelf IV,” Cousteau says. “Although architecturally Proteus is nothing like what he envisioned, I think this would be something that would be very exciting to him.

"I would hope that it would be because I'm certainly taking cues from education I received from my family as well as the pioneers on Calypso. So it's very much in that vein and one that I hope will mark the next step in ocean exploration.”

Humans have explored less than 5 per cent of the ocean world, and many questions remain unanswered. With Proteus, Mr Cousteau intends to change all that, while also helping society appreciate the importance of the oceans as the world’s life support system.

As he puts it: “No healthy oceans means no healthy future.”