Cheating in exams has gone on for as long as people have been made to sit written tests.

And with the ever-advancing pace of technology, breaking the rules via smartphones and earpieces has probably made the task even easier.

Now, however, new gadgetry could just be levelling the playing field – this time turning the tables by bringing exam cheats to book.

Manufactured by the Swedish firm Tobii, a high-tech pair of glasses, which tracks the wearer’s eyes, can pinpoint exactly where an individual taking a test is looking.

And if the wearer's gaze wanders - such as to the desk of a neighbouring student - then their deception will be caught.

“The glasses record everything you see,” said Prof Justin Thomas, a psychology researcher at Zayed University and one of two researchers who reviewed the technology.

“They are also fitted with a sensitive mic. If you see it, we see it; if you hear it, we hear it.”

Recent research by the International Centre for Academic Integrity compiled global surveys of cheating spanning the 12 years from 2002 to 2015, including data for 71,300 undergraduate students.

They found 39 per cent of students reported having cheated on an exam, while 64 per cent said they had cheated on a written assignment.

In a study of the effectiveness of Tobii's glasses, researchers carried out a mock exam undertaken by 30 first-year undergraduates at Zayed University in the UAE.

Three students acted as cheaters and wore eye-tracking glasses that recorded exactly what they were looking at and made audio recordings at the same time.

When the team reviewed the footage, they identified all 22 instances where the volunteers had attempted to cheat.

"We replayed the exam footage – kind of like VAR [video assistant referee] for exams. If we saw foul play, we flagged it," said Prof Thomas, who is also a columnist for The National.

“Examples included looking at a phone, looking at cheat sheets or looking at another student’s paper.

“The only way to cheat would be to cover the camera with your finger and then cheat.

“We made a rule that interference with the camera was to be taken as cheating.”

Prof Thomas, who co-authored the paper with Dr Adam Jeffers, an assistant professor at Zayed University, acknowledged the technology was currently “too expensive” to introduce on a large scale.

But given time he predicted the cost of the glasses was likely to come down dramatically, becoming “as cheap as chips in a few years”.

The main challenge to the device, he said, was to automate a way of reviewing the footage to reduce the man-hours it took to check multiple students.

“We envisage that a machine-learning algorithm could be developed to review the footage at high speed and just flag up anything suspicious,” said Prof Thomas.

“The suspect sections could then be reviewed by traditional proctors who would deem if the student had violated exam integrity.”

Prof Thomas said the glasses were unlikely to lead to “false positives”, where innocent students were accused of cheating.

He said instead, the technology could protect students from mistaken or unfair allegations.

If the glasses were fitted with retinal scanners, for example, this could confirm that any given candidate was who he or she claimed to be.

Imposters in exams have been known to sit papers for a fee, ensuring their clients passed.

Dr Irene Glendinning, a researcher in academic integrity at Coventry University in the UK, said eye-tracking glasses might be effective against multiple types of cheating.

She said these included collusion, copying, using crib notes, receiving spoken messages and using a smartphones.

But she said the technology would still prove redundant against other forms of cheating, such as a student leaving an exam room and accessing materials in a toilet.

Dr Thomas Lancaster, a senior teaching fellow at Imperial College London who has researched issues around academic cheating for two decades, said “no way of trying to stop cheating is infallible”.

“There’s probably more temptation to cheat than there used to be, because we now have a system where people’s lives depend so much on their results,” said Dr Lancaster.

An alternative method tried in some countries, particularly in eastern Europe, is actually filming students in exams, said Dr Glendinning.

“It’s kind of an arms race,” said Dr Glendinning, referring to the constant battle between new prevention techniques and the ability of students to find different ways to beat the system.

In a statement, Tobii said its glasses were "designed to capture natural viewing behaviour".

"Wearable mobile eye-tracking systems open up entirely new opportunities for behavioural studies," it said.

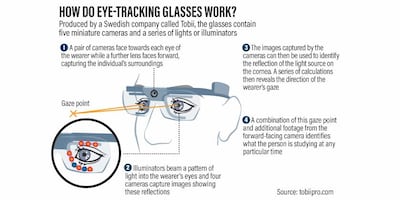

How do eye-tracking glasses work?

Produced by a Swedish company called Tobii, the glasses contain five miniature cameras and a series of lights or illuminators.

A pair of cameras face towards each eye of the wearer while a further lens faces forward, capturing the individual’s surroundings.

The illuminators beam a pattern of light into the wearer’s eyes and four cameras capture images showing these reflections.

The images can then be used to identify the reflection of the light source on the cornea. A series of calculations then reveals the direction of the wearer’s gaze.

A combination of this gaze point and additional footage from the forward-facing camera identifies what the person is studying at any particular time.