Long before the discovery of oil, desert Bedouin in the Emirates often subsisted on dates and milk from their beloved camels. It was a simple diet that kept them remarkably healthy, mostly because camel milk is a nutritional powerhouse.

Tests have shown it to have less than half the fat and 40 per cent of the cholesterol of cows' milk, and three times the vitamin C. People who are lactose-intolerant can drink it, it is said to trim blood sugar, ease food allergies and keep random colds and flu at bay. Tasting just slightly saltier than cows' milk, and dubbed "the white gold of the desert", it remains a vital part of the diets of Emiratis and other desert dwellers.

Now camel milk may soon become part of European diets as well. For several years, staff at the Emirates' largest camel dairy, the Emirates Industry for Camel Milk & Products, have been pushing to get the product on to store shelves in the EU. The application process has been long and arduous, but now there are indications that such an export market could develop within two years. "Sheikh Mohammed is behind it, and he always asks, 'How far are you with the regulations? I want to export it'," said Dr Ulrich Wernery, a veterinarian who originally came up with the idea of a camel dairy.

Dr Wernery, the scientific director of the Central Veterinary Research Laboratory, was flying to the UK in 2000 with Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, Vice President of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, to treat a sick horse owned by the sheikh, and he spent part of the flight expounding on the benefits of camel milk. The Dubai dairy opened two years later, and has grown from 200 camels to 3,000 - although only about 800 are yet old enough for milking. Each day it pumps out 4,000 litres of camel milk, bottling and selling it under the name Camelicious.

The prospect of exporting the UAE's camel milk to Europe - as well as keeping up with the demand of thirsty domestic consumers - could lead to another dairy farm opening in the coming years, Dr Wernery said. Dr Wernery has already done extensive research to confirm that camels in the Emirates are free of foot-and-mouth disease. Now, he said, his staff are addressing concerns raised in Brussels about the import application, notably proving that the exported camel milk has been pasteurised. He said he expected these issues to be resolved by next year, thereby opening the door for export plans to proceed in earnest.

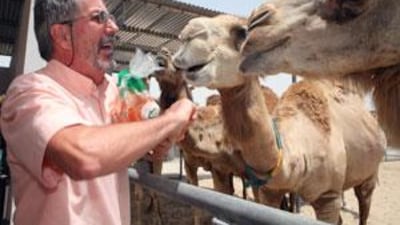

The EU confirmed that an application for import access had been made from the UAE, but would not comment further. East of Abu Dhabi, Al Ain Farms for Livestock Production is also increasing its camel milk production, albeit on a smaller scale. Here, staff still mostly milk their camels the old-fashioned way: by hand, into large silver bowls, producing more than 2,000 litres per day. But that is about to change, as there are plans to boost the herd from 500 to 800 animals within two years.

Although the immediate goal is to satisfy domestic demand, the company's research and development department is working on ultra-heat treatment of its milk to give it a longer shelf life. It has turned out to be a painstaking process, said Shashi Menon, the company's sales and distribution manager. "Unfortunately with camel milk there is very little research going on in the Western world. You cannot share work; you cannot take something and build on it. You have to start from scratch," he said.

Aside from red tape and health regulations, there are other hurdles to overcome. The UAE's dairies struggle to keep up with domestic demand for milk. Camels are also notoriously cantankerous creatures, prone to holding their milk back, which leads to an unreliable supply. Then there is competition from heavy producers, such as Somalia and Saudi Arabia, which have more than double the Emirate's 40,000 metric tons of annual production, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

The FAO pegs the potential world market for camel milk at US$10 billion (Dh36.7bn), with hundreds of millions of potential customers in Arab countries, Africa, Europe and North and South America. Last autumn the Vienna-based chocolatier Johann George Hochleitner launched Al Nassma, a company in Dubai that uses Camelicious products to produce the world's first camel chocolate. In the ensuing months there have been enquiries from as far away as the UK, South Korea and Canada, said the company's general manager, Martin van Almsick.

He said the company's main export focus in the short term would be on GCC countries, which expressed "immediate interest", but that eventually the export target would widen. "This is a fantastic product," he said, "and I am sure within five to 10 years it's going to make its way to the rest of the world." amcqueen@thenational.ae