During times of crisis and disaster, most people turn to governments and humanitarian charities.

But one Dubai company is showing that the private sector can make a difference – by building entire communities for Syrian refugees in a matter of months.

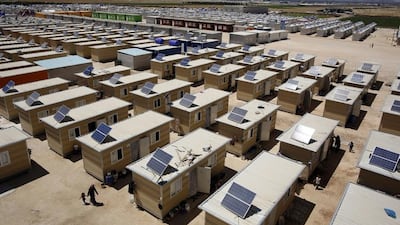

Modular and Mobile has built miniature cities that include homes, healthcare centres, schools and even kitchens and mosques.

The company was conceived three years ago by Briton Ben Long, 41, and Mete Ozbek, 53, from Turkey.

A year later, they set up in International Humanitarian City, already home to nine UN agencies and 50 NGOs. There, they were developing their first project, which was mobile bakeries.

“Mete and I met in India. We were both living on a farm, bizarrely,” recalls Mr Long. He was working on a food project on the farm, owned by an acquaintance of Mr Ozbek.

“We had both run businesses abroad, all over America, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Spain. So we were quite international people and, suddenly stuck in the middle of nowhere in India, we were living in this world where your eyes were open to all sorts of ways in which other people live.”

Mr Ozbek adds: “In India, you see everything in the street. We had a car, but we felt shame driving it around when people were living in the street.”

The two soon agreed that modular housing had to be the way to go.

“Why are people living in these sorts of situations when we can provide new, modern houses and build communities very quickly and provide everything they need?” Mr Long says.

At the same time, the Syrian civil war was intensifying and the duo heard that bakeries were being targeted.

Mr Ozbek, with a background in restaurants, suggested they design a bakery on wheels.

He was working in Saudi Arabia and took the idea to donors there, who funded two of the mobile units.

Inspired by how quickly the project bore fruit, the pair decided to set up shop in International Humanitarian City, with which Mr Long was familiar, having worked in the humanitarian sector.

“We’ve got seven purpose-built communities now,” he says. “Homes for 40,000. Modular homes, schools, hospitals, community facilities and mosques.

“We’ve also got mobile solutions, so any solution that you want, if you want it with wheels on it, we also do it. We’ve done seven mobile kitchens.”

Among the mini-cities are the Kilis Refugee Community in Turkey, and the Siccu Refugee Community in Syria. They have 1,000 homes for 6,000 people and come equipped with a wide range of community extras.

At Oncupinar Refugee Community in Turkey, they resolved a land shortage problem by building two-storey homes that housed a total of 10,000 people.

“When we first started, we used to do blocks of 100. Now, because the scale of the situation has become worse and the charities have become more trusting, we’re doing whole camps,” Mr Long says.

“We’re doing three camps at the moment. We’re finishing one that’s 900 homes, one is 800 homes and one is 700 homes.”

The company has also secured land and support for a project in the Kurdistan region, where there are 2 million refugees and internally displaced people, and a project in Hamburg, the first phase of which will house 4,200 people.

It is working on an orphanage project on the Turkish border with Syria, with 35 two-storey villas housing 24 children each for a total of 850.

As the company has grown, it has taken more control of the processes. It now has factories in northern Turkey and along the Syrian border, and a fleet of vehicles delivering daily.

It has teams of architects, engineers, project managers and more, up to 300 at a time.

“We’re basically planning small towns for a lot of people, so we need to know exactly what our capacity is on a daily basis,” says Mr Long.

Houses are built in factories, taken apart, sent off and then rebuilt on site, usually, in the case of Syria, by the refugees.

“If they want to build a mosque or a school in the middle of Africa, we can do it. Quickit is our standard but versatile product line that we use for refugee housing, and can also be used for mosques, clinics and schools.

“If we are looking for more long-term solutions or better quality, we will use Kozalife, which we use for everything from schools, mosques, hospitals and clinics, to municipal buildings, orphanages, homes, villas and recently a hotel.”

The houses, mostly designed to last 20 years, consist of a light, high-strength steel frame, high-density polyurethane panels, double-glazed windows and reinforced doors.

They also have a light steel mono-block flooring system for a strong foundation. The steel frame is locked into place by the roofing system.

“This is all very modern technology but it just means you can build very quickly,” Mr Long says. “Everything’s prefabricated off-site and we just come and build it. Everything’s numbered as it comes through the machine so it just clicks together like Lego, more or less.”

The houses and mobiles are built horizontally, making them stronger than the norm – vertical-builds – and more resistant to earthquakes.

Larger projects are built more strongly and all materials meet international best standards, be they rockwool insulation, moisture thermal barriers or fibre-cement composite exterior wall claddings.

Mr Long says it is looking like there will be no short-term solution to the plight of Syrian refugees, which drives the company to innovate even further.

One example is extending porch areas and installing curtains to give residents private outdoors space where they can cook and relax. Two-storey units have bathrooms outside.

“The people who are living in these units are the people who have lost everything,” he says. “They just didn’t have time to gather anything, they had to go.

“The people who have a little bit more are the ones who have travelled to Europe, and the ones who have more than that are the ones that have managed to get everything and travel and are now moving here. So, there’s people with whole ranges of problems.”

Many of the camps are remote and do not have access to water or electricity, so the company also installs running water and independent solar panels, enough to power fridges, cooking units, a few power sockets, a kettle and a fan.

Mr Long shows an image of a new community in Syria, where houses are being installed next to a set of tents.

“You have your old issue of who moves first,” he says. “You have to deal with things like that, but you’re working with very experienced agencies on the ground and we don’t get involved.” Although the business retains a large amount of control over its operations, it is also hugely dependent on partnerships.

“We’re working with a very experienced humanitarian aid organisation on the border who have been dealing with this for many, many years.

“It’s not taking risks. It’s just of matter of taking calculated decisions and making sure we’re doing the right thing for the people who are moving in there and living there. You never want to put anybody at risk.”

Its business model is based on connecting donors to charities.

“Basically, everything will always go through tender and the first contact we won through a tender process – best price, best quality.”

But the company soon found a gap in the market and decided to take the initiative in making things happen.

In the case of a refugee camp in Turkey, Mr Long says: “We went to the Turkish authorities and said: ‘We believe we can raise funds to build camps. ‘Can you give us access to land?’ and they said yes.

“We’ve then designed the perfect refugee camp. We’ve then rendered it with beautiful drawings and such.

“We take it to the donors, we present it, we say ‘This is a project, it’s going to house 6,000 people, we’re going to give them school education, fresh running water, it’s going to cost you X and they say, ‘Right, let’s do one’.”

The refugees building the camps are paid the same rates as Turkish contractors would receive.

“It just gives them ownership of the project,” Mr Long says. “They build it and so they’ve got pride in it. And when everyone moves in, they maintain it as well.”

There will generally be 100 people on site, trained to build 1,000-home communities in three months.

“And then we do mobile hospitals, toilets, registration centres, operating theatres, and we design them to look like tiny little houses, so they’re disguised,” Mr Long says.

One of their bakeries was targeted once. Fortunately nobody was hurt, and they “got it up and running again”.

Although Mr Ozbek says he has had to make sacrifices, like spending less time with his family in Turkey, he is happy.

“We had already done lots of things in our previous life. We were successful. But then, we needed to do something for other people and that’s why, now, we are quite happy it has turned into a reality. Now, we even dream of putting a garden in.”

Mr Long adds: “When we first started, we said we didn’t just want to provide a unit, somewhere to live in. We wanted to provide a community feel and that’s what it is.

“When you go to most camps, it’s very, very difficult to see people having to deal with that. So we set out to design and build the best refugee camps in the world.”

halbustani@thenational.ae