Schools in the UAE reported record A-level results this year, as pupils were awarded teacher-assessed grades in the absence of examinations.

Tests were cancelled for the second year running owing to the pandemic, and instead teachers used a combination of coursework, mock exams and essays to determine grades.

Teenagers in the UK also achieved record results, with 44.8 per cent getting A* or A grades, but British experts expressed caution that many of these results may be inflated.

The concerns of pumped-up grades have been echoed by teachers in the UAE.

Mark Leppard, headmaster at The British School Al Khubairat in Abu Dhabi, had one explanation for why the results were better than normal.

“There has been a grade inflation and the explanation for that is borderline pupils. The teachers would be asked if the pupil would achieve an A or a B, for example,” he said.

Staff would be more likely to give the pupil an A than a B, whereas if the pupil had sat the exam, he or she could have received either grade, depending on performance.

“As a consequence, last year and this year, the results are slightly inflated,” he said.

The school did take steps to remove bias and to ensure pupils were awarded accurate results.

Pupils’ names were removed from exam papers to maintain anonymity, and six or seven levels of checks were put in place, with several teachers and the headteacher looking at grades before they were sent to the boards.

Furthermore, evidence of each pupil’s achievement was set in place before exams were cancelled, and the school used standard mock exams papers for internal tests so that the difficulty level was consistent.

At Dubai British School Emirates Hills, the results were better than in previous years.

This year, 86 per cent of the A-level results at the school were between A* and B, compared with 78 per cent in 2020, 70 per cent in 2019, 67 per cent in 2018 and 61 per cent in 2017.

BTEC diploma results at the school also improved consistently, with 81 per cent of entries securing A* to B in 2021 compared to 55 per cent in 2016.

Sinead Kehoe, head of secondary at Dubai British School Emirates Hills, said the school gathered evidence over two years to determine their pupils’ grades.

Teenagers’ portfolios were assessed, their coursework for BTEC was externally validated and candidates’ names were removed from exam papers.

“I think that the quality assurance was as fair as it could possibly be. As a school, we have had professional training for teachers on objectivity,” she said.

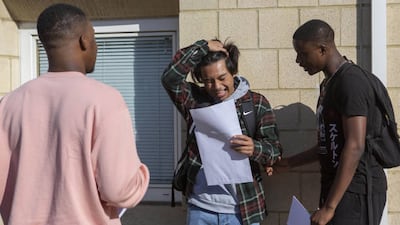

Sama Salman, 18, a British pupil at Brighton College Abu Dhabi, had initial reservations about teacher-assessed grading.

“I felt sometimes it was harder to show your potential to the teachers throughout the year,” she said.

“I was worried some people would end up getting grades they would prefer because of teacher favouritism.

“It was less standardised and there could be bias.”

In the end, however, she said teacher-assessed grades worked out well.