While exploring the impressive Museum of Liverpool, I studied a photo of travellers alighting from a passenger ship at the city’s docks in the early 1900s. I scanned this crowd for tourists who appeared to be from the Middle East. Because, in this era, Liverpool became an unlikely tourist destination for Muslims from around the world.

That popularity was partly due to one extraordinary true tale. It involved an African adventure, a Caucasian “Sheikh”, an impressed Ottoman sultan, an English newspaper circulated to 80 Islamic nations and the establishment of Britain's first mosque, here in Liverpool. Although London has the UK’s biggest population of Muslims, Liverpool is arguably its cradle of Islam.

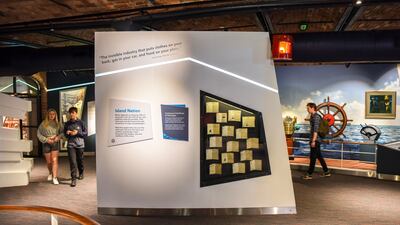

It was in the modern museums that occupy the docks on the eastern edge of the River Mersey, in downtown Liverpool, that I learnt that, in the 1700s, this northern English city was a global leader of the Industrial Revolution. Liverpool hosted the world’s first commercial wet dock and in the 1800s became one of Europe’s busiest ports.

Now some of its docks have been turned into the city’s main tourism precinct. They host the Museum of Liverpool, Tate Liverpool art gallery, The Beatles Story museum, the Maritime Museum, the International Slavery Museum, and a host of restaurants, bars and cafes. In the early 1900s, this waterfront was where most foreign tourists began their English holiday. That included many from the Islamic world, who savoured it here before exploring Europe.

The city’s status as a hub for Muslim travellers was partly due to William Quilliam. This white British man became Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles. His story was put back in the spotlight by the 2021 release of the book Islam in Victorian Liverpool, a translation of an 1890s travelogue by Turkish writer Yusuf Samih Asmay, based on his visit to the city.

Nowadays, there are about three million Muslims in the UK, making it the second-largest religion after Christianity. But in the mid-1800s that number was comparatively minuscule. Small Muslim communities existed in East London, Cardiff, South Shields and Liverpool. Their members were mostly maritime workers of Somali, Bengali or Yemeni background.

Then, in 1882, Britain’s relationship with Islam was altered by a trip to North Africa by Liverpool lawyer Quilliam. During his time in Morocco, Quilliam became fascinated by Islam. Five years later, aged 31, he converted from Christianity to Islam and changed his name to Abdullah. He was reputedly the first white British person ever to do so.

Quilliam became so devoted to Islam that he began giving regular public talks about his new religion. These lectures had a profound effect on Elizabeth Cates, a young woman in her twenties, who later was a prominent member of Liverpool’s Muslim community.

She changed her name to Fatima and became the first of about 600 Liverpool residents – many of whom were white and middle class – to convert to Islam over the following 20 years. This unique Muslim community was centred around the UK’s first Islamic house of worship, in a building on Liverpool’s Mount Vernon Street.

Soon that grew into the Liverpool Mosque and Muslim Institute, on Brougham Terrace. Tourists who visit this town house now will find it hosts the Abdullah Quilliam Society, a group that is aiming to restore this former mosque.

Now there are close to a dozen mosques or Islamic prayer centres in Greater Liverpool. Muslim visitors to this city can attend prayers at the Masjid Al-Rahma, the Liverpool Mosque, the Shah Jalal Mosque, Al-Taiseer Mosque and Bait ul Lateef Ahmadiyya Mosque, to name a few.

Such variety of options did not exist in the late 1800s. Back then, the mosque on Brougham Terrace was not only a place of prayer, but also hosted a madrassa, library, orphanage, Islamic museum, literary group and a printing room. It was from this latter space that Quilliam launched his boldest venture, one that made Liverpool’s small Muslim community famous across swathes of the Islamic world.

He led a team that published The Crescent. This weekly newspaper focused on Islamic topics and, remarkably, came to be read in at least 80 Muslim countries. The Crescent soon earned a powerful fan: Impressed by the newspaper and its influence, Ottoman sultan Ahmed Hamid II contacted Quilliam. The sultan granted him sheikh status, and also helped fund his Liverpool mosque.

The reach of The Crescent, which published about 800 editions up until 1908, helped attract many Muslim travellers to Liverpool, where some attended its mosque. That newspaper ceased when legal trouble prompted Quilliam to leave the UK for Istanbul.

In his absence, the mosque was shut and the building sold. Now, more than a century later, this premises is back in the hands of members of Liverpool’s Muslim community. If the Abdullah Quilliam Society is successful, the historic structure will soon host a mosque once more. And this building will again become an attraction for Muslim tourists from around the world.