Imagine being able to work out the ‘true’ value of a footballer with accurate scientific data analysis of their ability and how they would fit into a team.

Or being able to understand the player’s big-match temperament and how they deliver under pressure.

Even better — imagine a version of VAR that is faster and less controversial.

Well, that day could be drawing near with the advent of groundbreaking technology that can be placed inside a ball, capable of providing a gold mine of information for clubs to help guide them in the transfer market and beyond.

The so-called smart ball has been in development for six years and is ready to be launched in rugby at this year’s Six Nations Championship, which starts on Saturday.

The technology will provide statistics on kicks and passes that can be relayed in real-time to teams and fans watching on TV.

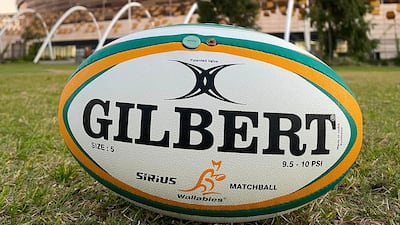

Pioneered by English sports data company Sportable and developed alongside rugby ball manufacturer Gilbert, the sophisticated technology has myriad applications in virtually any ball sport.

It is expected to be, quite literally, a game-changer.

“Our mission statement is to revolutionise how we view, understand and interact with live sport,” said Peter Husemeyer, a former Nasa scientist with a doctorate in nuclear engineering.

“There is not a sport that is off limits.

"Traditionally, a lot of kicking coaching in rugby has relied on stopwatches to measure hang-time and cones for training for box-kicking accuracy. There was no accurate, repeatable way to scientifically measure kicking performance. This is where we come in.”

Eureka moment

Born in South Africa but now living in London, Husemeyer and his business partner and best friend, Dugald Macdonald, started the business in 2016.

Husemeyer gave up a career at Nasa to follow his dream. Macdonald used to work in private equity.

They had their 'eureka moment' after watching a game of ice hockey and two players collided at speed. They thought it would be great to know the forces at work but no information was available.

They had always been admirers of Hawk-Eye, which has had a big impact on many sports and has become a household name in tennis, cricket and football.

That system is based on cameras tracking the ball and can be less effective in contact sports. Husemeyer and Macdonald came up with the idea of having the technology inside the ball itself and set about building a prototype in their garage.

“It became obvious to us there was a high demand for that missing data set," Husemeyer said.

"It was the thing teams didn’t have. We unearthed this latent demand for insight into how skilful players were and how they were performing in centimetre-accurate terms.”

How does it work?

In the rugby version, an ultra-lightweight microchip and battery sit just below the valve. A gyroscope is also embedded.

These relay data to a suite of up to 20 portable sensor beacons and then on to computers on the side of the field, virtually in real-time.

“Each one of the beacons talks to the ball 20 times per second,” Husemeyer explained.

“The ball relays that information about its position, its spin state, the acceleration it is undergoing and can discern to within a few centimetres the distance the ball has travelled — either by kick or pass, the velocity with which the ball has travelled, how many rotations it has gone through and how fast it has spun.

“We are able to piece all that information back together at millisecond-latency to work out what is happening in a game using machine-learning classification algorithms.”

The development stage included placing the ball under extreme pressure at a laboratory at Loughborough University using a robotic mechanical leg to ensure the chip did not break.

They also had to make sure that embedding the technology did not change how the ball — which weighs about 455g — looked and felt when in use.

While the initial focus will be on the kick and pass, the next phase of development could, for example, adjudicate on a forward pass and whether the ball has been held up or grounded over the line — the latter helping to greatly reduce time delays in decision-making.

“We had always wanted to make the game better, faster, and to bring officiating into more of an exact science to help referees, who increasingly have the hardest job out there,” said Husemeyer.

"We felt the technology we could bring to the game would be answering key critical problems in the sport."

New stats for TV fans

TV viewers will be treated to a new set of statistics which will appear on screen to enhance their understanding and enjoyment.

Broadcasters will be able to show the distance and speed of a pass, how long the ball spends in the air and the average territory gained on penalty kicks.

”The key point is we are giving fans the data that they are interested in knowing about while they are still curious,” Husemeyer said.

“You want to satisfy that curiosity while it is at its peak.”

The tech has also been trialled in boxing in Britain to track boxers' heat maps and which fighter is controlling the centre of the ring, and in showjumping to track the movement of horses and riders.

“What is fascinating is that the data science we have built even around human-centric algorithms actually translates to horses.

“We have done showjumping with the tracker in the horse’s bridle, which produced some fascinating data. We could see the horses that landed most softly after a jump conserved momentum and were overall faster around the course.

Football the 'holy grail'

Football is the holy grail for Sportable, where it has identified some "major challenges", for both teams and broadcasters, that it says it can help solve by providing accurate, real-time data.

"For example, training for set plays, whether it is a corner or free-kick, being able to know where the players are in relation to the ball and what the ball is doing, how it is moving, how accurate your deliveries are, is very valuable," said Husemeyer.

“We talk about standard deviation from where you can or want to put the ball. That is your big-match temperament (BMT).

"The higher your standard deviation, the lower your BMT. If you can deliver the ball on a dime every time, your standard deviation is low and your BMT is high.

“What athletes are training towards is to have accuracy when it matters. Being able to track the ball and to say that you can place it with pinpoint accuracy and have that to be predictable so your teammates can count on you — that is how you win games.

"The thing about data is that it becomes more valuable the more you have. You start to be able to glean and mine deeper insights.”

Since its introduction in leagues and competitions around the world, VAR has had plenty of critics.

Husemeyer thinks he could learn from VAR’s introduction to bring a faster solution for contact sports where reviews often take several minutes.

"Getting electronics into inflatable sports balls is very tricky. These are balls designed to be kicked by the world’s premier athletes so getting your electronics to survive those very violent events you can imagine was not easy,” he said.

“Our technology is portable, wireless, cost effective, easy to set up and very low latency. The time it takes for an event on the field to show up on the screen is only a few milliseconds.

"Our intention is to bring these insights to every sport in the world. We want to make sports in general fascinating and engaging and more enjoyable for fans."