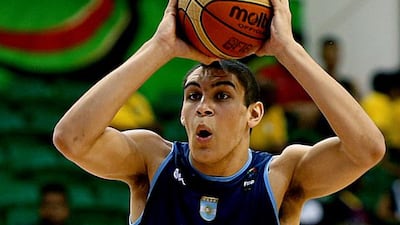

Argentina’s Lucio Delfino, like any basketball player, faces incredibly long odds of making the NBA, as his brother Carlos has done.

Just to play at a high-professional level in his home country, the Fiba Under 17 World Championship standout will need to refashion much of his game as his growth appears to have stalled and he seems set for a shift in position.

It will be a significant challenge for Delfino as positional roles in basketball require different skills and responsibilities that often take years of intuitive understanding to perfect.

But, as far as challenges go, it certainly will not be the biggest obstacle Delfino has overcome in his young life.

He was born with a brain tumour, one that required five surgeries – one per year, he said, starting when he was three – to remove what he likened to a mole from his head.

While most children who reach his level talk about playing their first basketball on mini-hoops at age two or three, Delfino did not start until he was eight, when the tumour was gone for good.

“I was travelling from Santa Fe, my city, to Buenos Aires every year for the surgery,” Delfino said of his early development. “It was a really tough life for a little kid, but now [looking back] I think it’s normal for me.

“After the surgeries, eight years old, I start my basketball career.”

He had plenty of help close to home in that regard. While he was travelling to Buenos Aires for his once-a-year surgery between 2000 and 2004, his brother Carlos was embarking on his professional career in Italy.

In 2003, Carlos became a first-round pick of the Detroit Pistons and has spent most of the last decade in the NBA.

Their father, Carlos Delfino IV, was a pro player in Argentina.

“They teach me every time we talk,” Lucio said. “They tell me this is a game, I have to enjoy it, play with enjoyment. I watch [brother Carlos] and I like everything he does, try to learn, I asked him everything that I want to learn.”

Now standing 1.98-metres tall, Lucio finds himself exactly the same height as his big brother.

But unlike Carlos, Delfino was taller for his age when he was younger and has developed more of a big man’s game – during the Fiba U17s at Dubai he has played mostly close to the basket.

To continue to advance, he need to transition to playing from the outside.

“He’s from a basketball family,” Miguel Santander, the Argentina Under 17s coach, said of Delfino. “Father is a coach and player, and Carlos, his brother, is very famous. He started basketball as a kid and his body [was bigger].

“But last year, that [began to] change.”

Santander is trying to move Delfino from power forward to a swing position.

“He has the talent, but he needs the time,” Santander said. “We need to work with him for the future, he need to play like a [small forward].

“I don’t know if NBA [is in the cards]. He has a very nice head, work ethic. With his family, he has the talent to play at a great level. Mentality is great. He has a good chance.”

Delfino has worked with his father on a position switch in addition to seeking out his brother’s advice.

“Basketball is every day. It’s something I never stop enjoying, it’s always fun,” Delfino said.

Argentina were knocked out in the round of 16 by Spain at the Fiba Under 17s on Tuesday.

But Lucio was undeterred, tweeting in Spanish what loosely translates to, “I wouldn’t change this team for anything”.

That attitude will help him as he tries to make the necessary improvements to approach the heights his brother has reached – including the national team’s pinnacle moment, when they won gold at the 2004 Summer Olympics. “I think every player in basketball dreams of that,” he said.

While Carlos earned the nickname “El Cabezon”, which roughly translates to “the big head”, the scars left from his little brother’s surgeries, winding marks that span the top of his skull, make his head unavoidably noticeable.

He used to wear his hair longer, which partly covered the scars.

Now, he keeps a closely cropped cut.

“It’s all done and it’s something that, when I was coming old, it’s me,” he said. “It’s a part of me.”

jraymond@thenational.ae

Follow us on twitter at @SprtNationalUAE