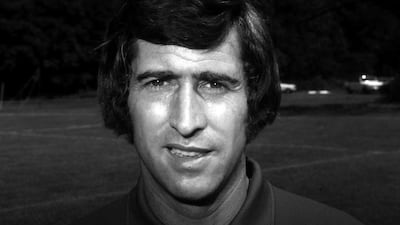

Gordon Banks was trending on Twitter on Sunday. It is 14 months since England’s finest goalkeeper breathed his last, but the death of his deputy meant Banks’ name circulated around social media again. Peter Bonetti was mourned eloquently by Chelsea, the club he represented 729 times, with tributes led by Ron Harris and John Terry, the only other players to make 700 appearances for them, and Petr Cech, the goalkeeper who passed his clean-sheet record.

In the wider world, however, Bonetti is remembered in the context of Banks. He is the latest of England’s World Cup winners to go although, after being unused in the 1966 tournament, his medal was awarded belatedly 43 years afterwards.

His solitary World Cup game was England’s last as officially the best team on the planet. Banks went down with food poisoning the night before the quarter-final against West Germany. Manager Alf Ramsey was so desperate for him to play he gave him the most perfunctory of fitness tests, only for Banks to fall ill again. Nervous, distracted by off-field issues, Bonetti played, though teammates Nobby Stiles and Francis Lee thought Alex Stepney should have done instead. England were 2-0 up when Bonetti dived over a Franz Beckenbauer shot. Perhaps he was culpable for Gerd Muller’s winner, too.

"There, so eloquent in its absence, was the value of a goalkeeper such as Banks," wrote Bobby Charlton in My England Years; his England years came to an abrupt end with his substitution in Leon. He never played for his country again. Nor did Bonetti. The 1970 squad was thought by some, Alan Ball included, to be stronger than their 1966 counterparts, but the greatest prize eluded them.

The rarity of World Cups mean they can be decisive. Careers are overshadowed by one moment on the global stage. For a later England goalkeeper, Rob Green, it was a more glaring blunder against the United States in his only match, in 2010. For a succession of players, it has been a missed penalty; Chris Waddle blazed over against the Germans in 1990, which is far likelier to figure in the first line of his obituary than his terrific performance in the preceding 120 minutes. There is often no chance of redemption: Bonetti was 28 in 1970 and 40 and retired by the time England even played another World Cup match.

Even in annual competitions, perhaps only the elite and the fortunate get a second shot. Didier Drogba, sent off in Chelsea’s 2008 Champions League final loss, scored the equaliser and the winning penalty in the 2012 shootout. But the nature of goalkeeping means mistakes can be costly. Loris Karius’ traumatic 2018 Champions League final is a case in point; for him, realistically, there will not be a second.

Bonetti illustrates the unfairness of defining a two-decade career by one moment or one game. Chelsea’s obituary did not mention England in the first 17 paragraphs, instead concentrating on his part in winning the 1965 League Cup, the 1970 FA Cup and the 1971 Cup Winners’ Cup, their first European trophy; until the last 25 years, no player had won more for Chelsea.

He was a pioneer of goalkeeping gloves and the club’s first goalkeeping coach; short for a keeper, his athleticism earned him the nickname ‘the Cat’ and, until Cech signed, there was no doubt he was the club’s greatest ever shot-stopper. That both Cech and Terry, two of a much younger generation, used the words “gentleman” and “legend” to describe Bonetti speak of his personality and his achievements.

It can be tempting to reduce a footballing life to one day. Bonetti shows how wrong it can be.