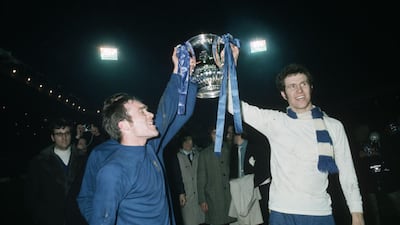

It was the longest final football's oldest Cup competition had ever known. Leeds United and Chelsea’s battle to claim the FA Cup ended 18 days after it began and took four hours of brutal combat to resolve. Fifty years ago on this day – April 29 – an exhausted Chelsea eventually lifted the trophy for the first time.

Half a century on, the Chelsea-Leeds FA Cup final replay maintains a cult clash, for reasons beyond the sheer length of the contest – 120 minutes for a 2-2 draw on a churned-up Wembley pitch and another dose of extra time at Old Trafford two and half weeks later.

That night was sapping, wild, forever on the brink of violence and full of suspense. When defender David Webb put Chelsea 2-1 up, 16 minutes from the end of extra-time, the London club had gained the lead for the first time in the entire saga. Leeds felt crushed.

The anniversary falls at a poignant time. Two of the game's central characters passed away this month; Leeds's Norman Hunter at the age of 76, shortly after testing positive for the Covid-19 virus, and former Chelsea goalkeeper Peter Bonetti, 78, succumbing to a long illness four days earlier on April 12. Both played more than 700 times for their clubs.

Both took part as young players in English football’s greatest triumph, members of the England squad who won the 1966 World Cup, though they celebrated on the margins; Bonetti the unused back-up for the fabled Gordon Banks, Hunter a reserve in case of any injury to captain Bobby Moore.

Club football would be their proudest stage. Few players so defined the upwardly-mobile Leeds and Chelsea of the 1960s and early 70s as Hunter and Bonetti. The latter, known as The Cat, was born in West London and was a stylist of a goalkeeper – not especially tall, but wonderfully athletic and agile – at a Chelsea that became famous for their flair.

Hunter came from the North-East of England and would for more than half his life be known by a nickname, ‘Bites Yer Legs’, a fans' tribute to his uncompromising tackling. For that, Hunter made an obvious emblem for a Leeds whose reputation for ruthlessness, their willingness to sacrifice artistry for pragmatism and to push the boundaries of the game’s laws, stuck with them.

But the image was also a caricature. Hunter was a fine passer, and his successful Leeds sides often brilliantly slick. “Norman read the game exceptionally well, and I knew that if he was 30 or 40 yards from me, with the ball on his left side, I would receive it straight to my feet,” remembered the Leeds midfielder John Giles.

Hunter had been in the Leeds side promoted from the second division in 1964. Five years later, he was key to the club’s first ever league title. In 1974 he won the league again. So iconic was Hunter to Leeds that team-mates referred to as the ‘son’ of Don Revie, the influential manager and later the head coach of UAE.

Bonetti enjoyed a similar rise. His first full season with Chelsea, 1961-62, ended in relegation. Within a decade, he had helped the club to their first ever League Cup, their first ever European trophy and by the end of that long, gruelling 1970 final to Chelsea’s first ever FA Cup.

Neither Bonetti nor Hunter had any real right to last through the 120 minutes of the Old Trafford replay. Bonetti was clattered to the ground by Leeds centre-forward Mick Jones, setting the rough-house mood, within the opening half-hour. That The Cat, in evident pain, limped on through the remaining 90-odd minutes, making vital saves, spoke of courage.

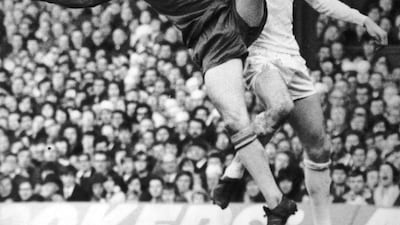

Hunter, meanwhile, was twice involved in scuffles where punches were thrown. He and his combatants escaped punishment. Part of the lasting fame of the 1970 final replay is about how it was refereed. Modern match officials tend to look back on it with a 21st century lens and estimate at least six red cards could have been shown. In fact, only one yellow card was issued by referee Eric Jennings during the 120 minutes.

But, by 1970, Leeds versus Chelsea fixtures almost had their own set of by-laws. Their contests were invariably rough, the spiky rivalry between glamorous west London and down-to-earth Yorkshire mixing with the heightened ambitions of both clubs. The grudge lasted, too, through the low times, when both Leeds and Chelsea were back in the second tier, on then through the resurgence of Leeds in the 1990s and the rise of wealthy Chelsea in the 2000s.

It is a rivalry Bonetti and Hunter had watched over the years in their roles as coaches and ambassadors for Chelsea and Leeds. It is one they had hoped to see snap and crackle again next season, with Leeds poised to rejoin Chelsea in the Premier League – if and when a Championship season in which Leeds have set the pace can be resumed.