A couple of years ago, perhaps the most remarkable footage of Liverpool’s season came when Trent Alexander-Arnold took a quick corner. Only Divock Origi, the likeable everyman of a striker parachuted in against footballing aristocracy, reacted. Liverpool 4 Barcelona 0. Anfield erupted.

This year, in a more solitary world, it was a man in his seventies, wearing a checked shirt and gilet, sat in front of a wooden cupboard and vase of flowers, delivering a mea culpa in a homemade video.

“I alone am responsible for the unnecessary negativity brought forward over the past couple of days,” said principal owner John W Henry. “It’s something I won’t forget.”

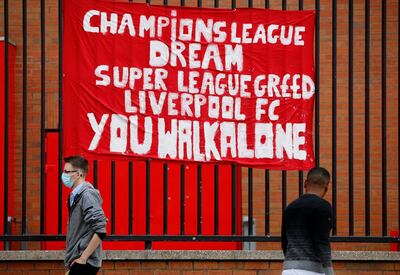

It is something he may not be allowed to. Liverpool’s withdrawal from the European Super League marked the biggest U-turn of Fenway Sports Group’s decade in charge.

Their initial participation, and status among the ringleaders, has represented their gravest mistake. It is evident they alienated their manager, their players and the fanbase. They demonstrated a continued inability to understand a club and a city.

These have been recurring themes during a regime that, with the 2019 Champions League, a 19th English league title that was 30 years in the making and Liverpool’s mushrooming value, ought to have been a rare success story in ownership.

FSG’s failures – Project Big Picture, £77 tickets, trying to trademark Liverpool and furlough staff – have all been their errors. This could prove the unforgivable one.

The influential This Is Anfield website said: “We are all FSG out now. The trust is broken, lost forever.” Jamie Carragher, a veteran of 737 Liverpool appearances and an iconic Champions League winner, said: “There's nothing left for Liverpool's owners. I don't see a future for the ownership of FSG at Liverpool.”

Liverpool were not the first of the six Premier League clubs to apologise for briefly joining the Super League – that was Arsenal – but Henry’s emergence from silence indicated the severity of their plight.

“The project put forward was never going to stand without the support of the fans,” said Henry. Yet Liverpool’s supporters were not asked. Anyone with even a cursory knowledge of their fanbase should realise they can mobilise and share some socialistic principles that Bill Shankly espoused and which Klopp shares. A decade at Anfield ought to have taught them that the European Cup is central to Liverpool’s identity.

And dividing a club was still more senseless when the manager is Klopp, who excels at forging bonds and harnessing the powers of unity and belief. FSG did not heed Klopp’s 2019 comments – “I hope this Super League will never happen” – and, by 2021, his view had not changed. “No, I don’t think it is a great idea,” he said on Monday, visibly irritated at being put in the line of fire.

His vice-captain, the straight-talking James Milner, said: “I don't like it one bit and hopefully it doesn't happen.”

His words were echoed by the players’ joint statement on Tuesday. “We don’t like it and we don’t want it to happen.” In Jordan Henderson and Milner, Liverpool have principled, experienced, authoritative figures. Like Klopp, they could have been valuable sounding boards.

But there is a recurring theme from out-of-touch owners. There are people at Anfield, many hired in the FSG era, whether director Kenny Dalglish or head of supporter engagement Tony Barrett, who could have told them how this would be received.

Either they were not consulted or they were ignored. If one issue is FSG lack a high-level executive who commands respect across the club, this has been an unnecessary blunder. It is unlikely FSG will choose to sell, but if reputation and trust is gone, it could prove the start of their long goodbye.