To find tranquility in Abidjan, it’s best to head for the banks of the lagoon. To find the heart of Ivory Coast’s most popular sport, or at least the motor that has driven the country’s football, go to the eastern edge of the Ebrie.

Here are the headquarters of ASEC Mimosas, the nation’s most celebrated club with an academy that not so long ago would have been deemed among the world’s most productive. Scan the roll of honour as you enter the site’s patchwork of pitches, classrooms and dormitories , and you’ll see listed the Toure bothers, Kolo and Yaya, the latter the great galvaniser of Manchester City’s modern rise and a European club champion with Barcelona.

There are the Kalous, too, Salomon, a Champions League winner with Chelsea, and his brother Bonaventure, later of Paris Saint-Germain. There’s Gervinho, later of Arsenal. There’s Didier Zokora, the most capped player for Ivory Coast’s national team and an asset to the midfields of various European clubs after he made the familiar journey abroad from ASEC.

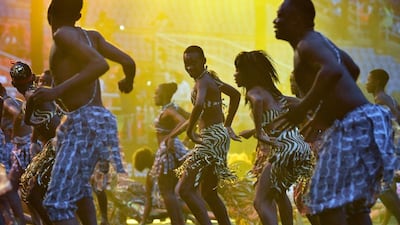

There will be more recent ASEC graduates, though less feted, among those representing the national team on Saturday at the new Olympic Stadium in Epimbe for the opening match of the Africa Cup of Nations, the first hosted in Ivory Coast for 40 years. It's a major chance for The Elephants, as they are nicknamed, to repeat their lone Afcon triumph, the 2015 victory that endorsed the so-called golden generation of Ivorian players, a high concentration of them brought through the ASEC hothouse.

If the champion side of the Toures and the younger Kalou, of Didier Drogba – a superstar whose football upbringing was largely in France – casts an imposing shadow, they also represent a different time, when the pathway between homegrown excellence and the top of the sport ran smoother. Ivory Coast has in the last decade lost its pre-eminent place among the nurseries of African talent. It now looks enviously at near neighbours like Senegal for how youth football is being run.

The enduring truth that almost none of the best African prospects stay in Africa for long – the comparative financial rewards for moving to Europe, or the Gulf, are vast – remains, but more and more leading players for the Elephants have also done their apprenticeships outside Africa. Of the 27 selected in Ivory Coast’s squad by head coach Jean-Louis Gasset for this Afcon, less than half came through Ivorian academies.

Partly that’s because, like other heavyweights such as Morocco, Ivory Coast have determinedly sought potential internationals from the country’s diaspora, players of Ivorian heritage who were born or grew up in Europe. The spine of Gasset’s best XI, from centre-forward Sebastien Haller, of Borussia Dortmund, through midfielder Seko Fofana, of Al Nassr, to central defender Willy Boly, of Nottingham Forest, all represented France at youth level.

Fifa rules on switching national team have eased in the past 10 years, and several African countries have been beneficiaries of the lighter regulations. But there is a risk that expatriate hiring also loosens the bond with supporters, with the locale.

Viewed from the academies of Africa, it can look like evidence their students are at an ever greater disadvantage, that a schoolboy player learning how to be a professional is on a faster track to the professional elite at a high-spec European academy than at home.

ASEC can feel like an island in treacherous territory. While the methods and learnings within the academy may be rigorous, there is no coherent youth league for the players to compete in. Coaches there bemoan the haphazard fixture list their young players have to contend with.

“You never know if your age-group team are going to playing against a side filled with players older than they say they are,” one tells The National. At senior level, ASEC, who were African club champions at the end of the 1990s, have, like Ivorian clubs generally, made a steadily reducing impact in pan-African club competitions.

Ivory Coast win 2015 Afcon - in pictures

The impulse for talent to leave young, pursuing contracts abroad, partly explains that. The superclubs of the continent’s richer leagues – Egypt, the Maghreb and South Africa – tend to dominate the African Champions League, but there is still nostalgia at ASEC for the days their young sides, plucked from the academy, could hold their own across Africa.

There is a residual pride in how the leadership qualities of their most celebrated graduates are now being realised, post-retirement as players. Yaya Toure is at the Asian Cup, as assistant coach to Roberto Mancini with Saudi Arabia’s national team. Bonaventure Kalou has served for the last five years as mayor of Vavoua, in central Ivory Coast.

And there is eager anticipation at how the Elephants’ homegrown talents dovetail with expatriate expertise at Saturday's first assignment, against Guinea-Bissau, of what the country hopes is a journey all the way to the final. Midfielder Oumar Diakite, 20, and striker Karim Konate, 19, are carrying the baton for ASEC’s academy, both transferred to RB Salzburg in Austria last season, both hopeful of making this Afcon a platform for their next big career step.