It's a sad day in football when the beautiful game loses one of its brightest stars. It's tragic when it loses two in the space of a week.

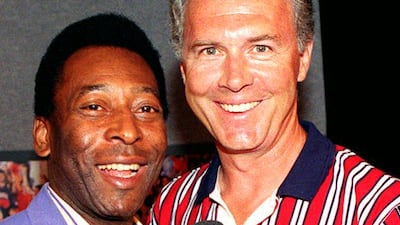

News of the deaths of Franz Beckenbauer, aged 78, and Mario Zagallo at 92 is a time for sadness and reflection on the careers of two men with legitimate claims to having transformed the game.

Zagallo's death last week was felt from the vibrant streets of Rio de Janeiro to the bustling metropolis of Dubai. The first of only three men to win the World Cup as both player and coach – Beckenbauer was the second – Zagallo earned his place in history and was never shy of reminding people of it.

In his seminal book Brazil 1970 – How the Greatest Team of all time won the World Cup, Sam Kunti described how Zagallo would ignore his questions to instead self-indulge.

"He was full-on vain. Here was a man who had spent a lifetime cultivating his own place in history, a man who would tell you of his glories, and would never pass on a chance to be thanked for his own largesse," wrote Kunti.

As a player, Zagallo was talented but limited. Perhaps that's unkind when judging anyone playing in the same era as Pele, Garrincha and Didi but while others may have accepted their fate and remained happy to watch from the sidelines, Zagallo instead reinvented himself and analysed where Brazil's weaknesses lay.

The Selecao's commitment to attacking football is part of its DNA. Zagallo, a winger by trade, began to drill into anyone who would listen that wide players needed to drop back into midfield to reduce being exposed. It seems trivial now but at the time the idea of an attacking player dropping back to help out his midfielders or defenders was anathema to many Brazilians.

If Zagallo the player was the disruptor then Beckenbauer was the likeable statesman who promised a better future in a Germany still reeling from the ravages of war.

Being blessed with an evocative nickname like Der Kaiser will always open pathways and so it was for Beckenbauer. Before the 1966 World Cup final, England boss Alf Ramsey had earmarked West Germany's 20-year-old sometime-defender-sometime-midfielder as a player who warranted special attention. And while the gnarly Nobby Stiles, England's pugnacious midfielder, was probably more suited to the role, it was Bobby Charlton, Ramsey's chief attacking threat, who was tasked with shadowing Beckenbauer.

The thinking was that, though Stiles would carry out the task better, England could not afford for their midfield anchor to be snapping at Beckenbauer's heels high up the pitch one minute only to find his defenders exposed when West Germany or Der Kaiser transitioned effortlessly between defence and attack the next.

Though not eponymous, few argue that Beckenbauer created the libero role, or at least mastered it. It was at club level with Bayern Munich that Beckenbauer redefined the role of sweeper to make the most of his offensive as well as defensive ability. Three successive league titles between 1972 and 1974 were followed by a hat-trick of European Cups from 1974 to 1976.

It was a golden era for German football in which Beckenbauer would earn the plaudits of teammates and opponents alike. Beckenbauer captained West Germany to World Cup success in 1974, two years after leading the team to victory at the European Championship. Football is usually defined by great attacking teams or players but there is a case to argue that the period between 1972 and 1976 belongs to Beckenbauer.

Zagallo and Beckenbauer were both establishment figures, tied by association and politics to either club or country – or both – but to view them as merely company men is folly.

Both were transformative and innovative, seeing the game far beyond the confines of the pitch. Just as they were as players, both were subtle masters at manoeuvring themselves into positions of power and influence.

Both would go on to coach their countries; both would lead them to World Cup success. If Zagallo the player can be judged conservative by Brazilian standards, Zagallo the coach was anything but. Zagallo won the first of his two World Cups with Brazil as a player in 1958 before repeating the feat four years later but it is his Brazil of 1970, that of Pele, Rivelino, Tostao, Carlos Alberto, Jairzinho et al, that is feted as the greatest team of all time.

If no team before or since could hold a candle to that side, Beckenbauer's West Germany that lifted the trophy in 1990 was a construct of ruthless efficiency and a dash of daring. Jurgen Kohler, Lothar Matthaus and Rudi Voller will never be remembered in the same vein as Brazil's Class of 1970 but their achievement in Rome was the embodiment of Beckenbauer's devotion to the fundamentals of football.

Indeed Beckenbauer and Zagallo were on a collision course to meet at that tournament. The UAE were drawn in the same Group D as the beaten 1986 finalists. But having led the Emirates through qualification, Zagallo resigned from his post before the tournament. West Germany won their encounter 5-1. It remains the UAE's only appearance at the World Cup finals.

Few attain the excellence Beckenbauer did as a player; none have come close to assembling and organising an attacking array of talent as Zagallo did with Brazil in 1970. Two men, bonded by brilliance.