It’s difficult to put into words just how much Monza – Sunday’s home of the Italian Grand Prix – means to Ferrari and their passionate following.

A sprawling royal park is a curious stage but there is palpable sense of the immense motorsport history in a lingering concoction of burnt oil and scorched brakes, the new buildings and old fences.

Once the scene of kings and princes on a sedate Sunday canter, the sprawling 700 hectare site has been transformed by a national obsession into a cathedral of worship for the fastest F1 race on earth.

And the speeds are such around what is effectively four straights joined by three Mickey-Mouse chicanes that accidents, even now, are inevitably serious. Topping 350kph will do that.

Over the decades 40 fans and 50 drivers have died, including Ronnie Peterson and Jochen Rindt, the sport’s only posthumous champion, killed at the 1970 staging. A fire marshal was killed by a flying wheel in 2000.

So along with the majesty and passion goes a tangible melancholy.

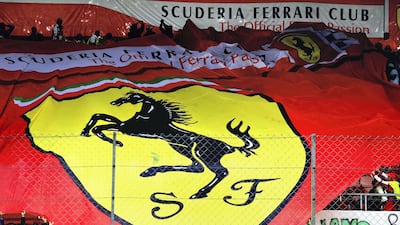

But still they come to worship, the Ferrari fans who have their own name – the tifosi – which quite literally means ‘those infected by a fever’.

To see a hoard of Maranello’s finest coming in and out of the circuit is to witness the modern equivalent of a feudal army, predominantly red, on the march. Giant flags fluttering, klaxons playing, flares spark and smoke bomb erupt to create a drifting red fog.

The tifosi cheer Ferrari drivers to the rafters and celebrate when rivals, even Italian ones, crash out. The race may be in progress but if their blood-red icons retire they head home en masse.

The park’s size is a both a blessing and a curse. Rabid fans flood over the walls in their thousands and disappear into the expansive woods making it impossible to patrol adequately.

I have jogged and driven the circuit at dusk and seen fans camped on the inner recesses, gathered around bonfires, built halfway up disused concrete grandstands, without fear of being removed.

In the 1990s I helicoptered back from an event at Lake Como and descended from the clouds to witness what could only be described as a small city of trucks, vans, motorhomes, caravans and seething humanity.

Outside the paddock gates the melee is the same every year. Barely controlled chaos.

Inside, what is supposed to be the calm, business epicentre of a global sporting enterprise, is transformed for one weekend into an anything-goes fashion show sprinkled with Italian madness.

My first experience of the track in 1987 as Ayrton Senna’s public relations man I was standing outside the pit lane garage after the race ended when a mechanic suddenly shouted “inside, inside”.

I dived in as the garage doors clanged shut the length of the pitlane. It became apparent why. Tens of thousands of passionate fans had found a gap and surged through the fencing to hammer enthusiastically on the steel doors. It was like being inside a drum.

My daily drive to the track took me past the gates of Villa San Martino in Arcore, owned by the nation’s most famous political figure of recent times, Silvio Berlusconi. The armed carabinieri lounging by the main gates are the most relaxed security detail in the world.

But the dichotomy that is Italy was never clearer than when I learnt from court papers that Berlusconi’s head of security there in the 1970s had been Vittorio Mangano, who died in prison in 2000, jailed for mafia activities including racketeering, kidnap and extortion. Berlusconi denied any knowledge of Mangano’s activities but later hailed the man “a hero”.

As far as the racing goes Ferrari will be praying this year’s event slides into oblivion as quick as the last round, which was their worst result in a decade.

Team boss Mattia Binotto, the figure most culpable, is right in at least one respect, they are at the centre of a raging storm. Passion cuts both ways.

Their fall from grace is such that last year’s winners at Monza are doubtful of a top 10 finish for their home race even at a circuit specifically designed to appeal to their greatest strength – power. Sadly it will only demonstrate the scale of its absence in 2020.

Perhaps it’s just as well the fans are banned by the pandemic. But I can promise you, however well the camera angles hide them, and however bad the omens are for their beloved Ferrari the tifosi will be close at hand on Sunday.

Closer, probably, than Charles Leclerc or Sebastian Vettel will be to Lewis Hamilton or Valtteri Bottas, that’s for sure.