Last week, media in the United States reported that the Trump administration had postponed an executive order designating the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organisation. The decision follows what seems to have been an intense debate in US policy circles. A state department memo decisively advised against the move, on the grounds that the Brotherhood is split into different branches and is legitimately involved in the politics of several Arab countries.

Increasing emphasis is being placed on a comprehensive approach that addresses the conditions that feed the terrorism phenomenon and the militant ideology that provides its cornerstone.

The final statement by the ministers of the Global Coalition against Daesh, following a meeting in Washington DC a week ago, illustrates this evolution of the thinking on counter-terrorism. “The Coalition supports enhanced efforts to prevent radicalisation and recruitment into Daesh and its branches by addressing the factors underpinning its emergence and continued appeal,” the statement read.

Yet the free pass the West continues to provide the Muslim Brotherhood contradicts the strong commitment made by the US and its partners to defeat terrorism and its ideology.

The US is not the first western country to discuss the Brotherhood’s ties to terrorism and extremism. In 2014, British prime minister David Cameron asked Sir John Jenkins, then the United Kingdom’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, to lead a policy review into the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamism more widely. The review covered the Muslim Brotherhood in the UK, parts of Western Europe and the Arab world.

The report was internal and thus never disclosed in full, but the main findings were made public in the House of Commons in December 2015. Its key conclusions included well known facts such as the deep anti-western outlook of the organisation since its origins, its lack of moderation and the dominant role of its Egyptian branch. It noted how Hassan Al Banna, the organisation’s founder and first spiritual guide, ultimately aimed to unite all Muslim societies in a caliphate. It also pointed out how the various national branches of the organisation “developed individual concerns and tactical approaches, but shared a common ideology”.

Specifically on the organisation’s links to violence and terrorism, the report explained how Sayyid Qutb, the Brotherhood’s key ideologue, “drew on the thought of the Indo-Pakistani theorist, Abul Ala’a Mawdudi, the founder of the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami, to promote the doctrine of takfirism”. Qutb’s thinking continued to be endorsed by senior members of the organisation and it inspired various transnational terrorist organisations including Al Qaeda. Attacks on western forces, as well as the use of suicide bombings against Israel and the killing of civilians, have been endorsed by senior members of the organisation.

In backing the findings of the review, Mr Cameron diplomatically stated that it supported “the conclusion that membership of, association with, or influence by the Muslim Brotherhood should be considered as a possible indicator of extremism”.

Last year, the House of Commons foreign affairs committee released a report that criticised the initial review. It focused essentially on two aspects: that the main findings “neglected to mention the most significant event in the Brotherhood’s history: its removal from power in Egypt in 2013, the year after being democratically elected, through a military intervention”; and that Sir John Jenkins was the wrong choice to lead the review because of his position as ambassador to Saudi Arabia.

It is striking that the foreign affairs committee placed so much emphasis on the overthrow of a Muslim Brotherhood government that, although elected, was everything but democratic. Had it not been for the military intervention, supported by millions of Egyptians, Mohamed Morsi and his cohort would quickly have turned Egypt into a chaotic Sunni version of Iran.

The argument that Sir John should not have been selected is also puzzling. At the time Mr Cameron commissioned the review, he was the most senior Arabist in the Foreign Office, with remarkable Middle East experience stretching over more than two decades.

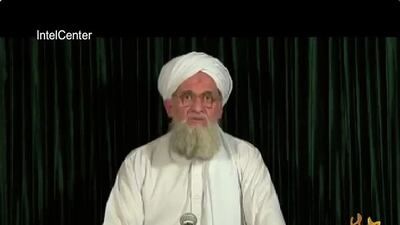

Various aspects not included in the review’s key findings are worth mentioning. Abdullah Azzam, Osama bin Laden’s mentor, was a member of the Brotherhood. So was Muhammad Surur, the hardline Syrian preacher and admirer of Qutb who played a prominent role in exporting the group’s ideology to the Gulf by politicising and radicalising traditionally quietist local Salafists. Al Qaeda’s current leader, the Egyptian Ayman Al Zawahiri, joined the Brotherhood when he was a teenager. And the list goes on.

Designating the entire Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation does raise difficult questions for the US government. What would, for example, be the effect of that move in Jordan, a close US ally where the local Brotherhood branch holds several seats in parliament?

There are, however, precedents to look into. Hamas, the Brotherhood’s Palestinian branch, is designated a terrorist organisation by both the US and the European Union.

Concerns about generating more instability in Lebanon have also led the EU to designate Hizbollah’s armed wing a terrorist organisation, while leaving out the militant group’s political wing.

A case-by-case approach could be an effective strategy for the US to curb the propagation of the Brotherhood’s radical ideology. There should be no illusions, though, about the nature of the organisation as a whole.

Dr Manuel Almeida is an analyst and consultant. His research focuses on the Arabian Peninsula and the crisis of Arab statehood. He is the former editor of the English online edition of Asharq Al Awsat newspaper and holds a doctorate in international relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science

On Twitter: @_ManuelAlmeida