Another UN general assembly week arrives in New York, and yet another avalanche of speeches, meetings and op-eds are launched addressing the same four-and-a-half-year-old dilemma: what should we do about Syria?

This year, Russian president Vladimir Putin has muscled into the spotlight with his unwavering solution: Bashar Al Assad must stay. While John Kerry described the US’s stance with typical ambiguity: Mr Al Assad should leave in an “orderly fashion” to avoid “an implosion”. If Mr Kerry had asked most Syrians today, they would inform him not to worry, Syria imploded many months ago, under the Obama administration’s watch.

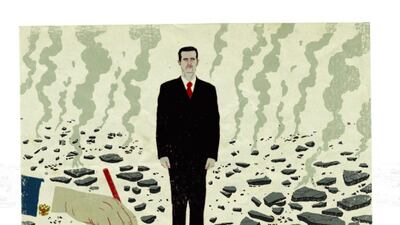

Years of gruelling war fuelled by Mr Al Assad’s vast arsenal of bombs and torture has left much of Syria in piles of smoky rubble inhabited by millions of suffering people, more than half of whom are displaced. Syrians started to become refugees in 2011, first in the hundreds and slowly into the millions, but only in the past few months, because tens of thousands of people decided to walk across Europe in search of safety, has the world frantically declared that there is an official refugee “crisis”.

Although Syrians have been told for years that our conflict is “too complicated”, the media, pundits and politicians alike have now reduced Syria to two simple questions: Should Mr Al Assad stay in power to end the war? And, should we let the refugees into our countries?

The complete detachment of each of these questions from the other is maddening but not surprising. Do these world leaders forget we have heard the same half-hearted and empty sentiments for years?

One notable scene took place in February 2012, three days after Russia vetoed a UN Security Council resolution condemning the Syrian government for its brutal attack on Assad regime opponents in Homs. Sergei Lavrov and Russia’s foreign intelligence chief visited Damascus to urge reform and dialogue. Instead of reform, the shelling of Baba Amr in Homs intensified.

The above report now reads like a cruel joke. Eleven months into the uprising, the death toll was – at the time infuriating, now incomprehensible – 5,400 people. Back then, Hillary Clinton used the term “Friends of Syria” as unironically as Russia dutifully spewed the phrase “reform and dialogue”. Syrian rebels dreamed of carving out a safe zone in the north but were afraid to “launch an offensive” without the international community’s support. They also feared that the regime would begin using air raids soon.

Imagining Syria before aerial bombardment is almost impossible. What would have happened if a no-fly-zone was enforced at the very moment that the Assad regime began dropping bombs on Homs only a few weeks later?

We wouldn’t be where we find ourselves today.

This week, Mr Putin reframed Russia’s role in Syria as a guarantor of peace, stability, secularism and even democracy, along with the government headed by the Assad clan. But Russia’s influence has rarely helped the vast majority of Syrians.

It’s no surprise that Russia’s (and Iran’s) interests are and always have been aligned with Mr Al Assad’s. The Assad regime is a precious Russian investment that provides influence in the region along with a strategic perk: a Mediterranean port.

Russia (and before it the Soviet Union) is the primary source of the regime’s weapons, from Scuds to helicopters to propaganda warfare tactics. Now, Russia is building a military base in Latakia and plans to fly fighter jets as part of a “non-coalition coalition” with the US.

So how can we be surprised that on Wednesday, Russian forces dropped bombs over ISIL-free cities including Homs and Hama killing over two dozen people including children?

This week, US secretary of defence Ashton Carter attempted to explain the “logical contradiction between Russian positions and now its actions in Syria”. These logical contradictions mean nothing to Syrians who don’t differentiate between a Russian plane flown by an Assad loyalist, an Iranian mercenary or a Russian soldier. We know who brings our people death. And we also know that many countries, including the United States, are watching as a genocidal air campaign enters its fourth year.

We used to say we have witnessed the limits of the world’s hypocrisy enacted on our country. We don’t say that any more. It’s naive to assume that, even now, we have reached those limits.

The solution in Syria has to begin with protecting civilians from the violence of both Mr Al Assad and ISIL. Anything less than this basic principle will not end the war.

The biggest killer by far in Syria is the Assad regime. ISIL is a distant second. But as we know, Russia won’t be fighting ISIL, and won’t bring democracy to the Syrian people they have begun to bomb. Moscow will continue to dole out the advice it gave Mr Al Assad in 2012 in Baba Amr. Russia and Iran will continue to obscure their role in the Syrian genocide.

Of course, there are complex geostrategic reasons for Russia’s growing role in Syria, rebalancing of foreign influence in the region, and lots of other fancy arguments that experts and political scientists are thinking about. For many Syrians, the current scene is easily deciphered: Russian soldiers are coming to the country to prop up a dictator and continue the slaughter and destruction.

Syrians who want the war to end in a just settlement that enforces the rule of law, democracy and equal rights for all its citizens have no friends left in the world.

Every so often, I’m asked to make the argument why Mr Al Assad and his deadly regime no longer have a place in Syria’s future. The very question seems like an insult. Then I remember to not answer would be a greater insult to our dead who were killed chanting for the tyrant to leave.

So why should Mr Al Assad go? He should go because the Syrian people deserve to live free from the regime’s security apparatus that has terrorised thousands of innocents over four decades.

He should go because no people in the world should live under the constant threat of barrel bombs on their homes. He should go because why must millions flee in exchange for the few to stay?

He should go because even when we convince ourselves that we live in a world of “no more good options”, it’s never acceptable to justify genocide. He should go because there will never be peace in Syria with him or his regime in power.

The questions asked by world leaders should be flipped: let Mr Al Assad go and let the refugees come back home.

It’s never too late to start making right and just decisions for Syria – and none of those options include the survival of the Syrian regime. But waiting, as we know, comes at a heavy cost.

My greatest fear, one that has materialised over and over since 2011, is that these very lines may also read like a cruel joke 36 months from now. It is when numbers like 250,000 dead and 11 million displaced make us wince and ask: Were there really so few dead, only that many refugees, back in 2015? Why didn’t we stop the violence when we had a chance?

Imagine what Syria could look like in a decade if we stop the bombs now. Imagine if we don’t.

Lina Sergie Attar is a Syrian American writer, architect and co-founder of KaramFoundation.org

On Twitter: @amalhanano