"You mark my words,” Edgardo told me indignantly. “They can talk all they want about Fidel, but one day the imperialists will be forced to have a drink with him.”

That was back in 1994, during a visit I made to Cuba, which at the time seemed on the brink of collapse. Edgardo was a veteran of the Castro years.

At that time – five years before the 1999 election of Hugo Chavez as president of Venezuela gave the Castro government a new oil-rich sponsor – Edgardo had no idea how Cuba was going to escape economic crisis.

But despite that gloomy moment, his pride was undiminished in the Cuban revolution as an expression of national dignity defying the Monroe Doctrine under which Washington reserved the right to shape Latin America’s destiny.

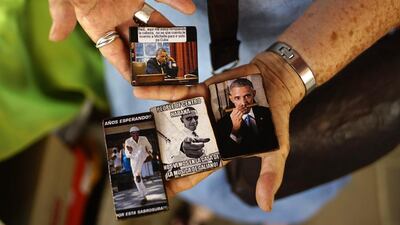

Twenty-two years after our interview, Edgardo has been vindicated. Cuba will next week welcome Barack Obama, the first US president to visit the island since Calvin Coolidge in 1928. And although he will not "have a drink with Fidel", he will meet president Raúl Castro, the younger brother to whom Fidel handed office in 2008. The visit effectively draws the curtain on half a century of failed US attempts to impose regime change on Cuba.

A policy that started with an attempted proxy invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, saw decades of dirty tricks and an attempt to strangle Cuba’s economy through a total trade embargo, nonetheless failed to dislodge the Castro regime. Indeed, that regime has survived 11 US presidents and counting.

Washington’s security establishment has known for decades that the embargo would fail. The only reason it has survived this long is because of the unique role of Florida, with its large and politically active Cuban exile population, in settling closely fought US presidential elections. So it was not only Republicans such as Ronald Reagan and George W Bush but also Democrats such as Bill Clinton and Mr Obama who promised to maintain the embargo until Cuba made democratic reforms.

But the domestic political calculations have slowly changed as younger Cuban-Americans have recognised the futility of the embargo – polls now show a majority of Cuban-Americans support president Obama’s engagement policy, even though it has been sharply criticised by Republicans and by the Cuban-exile leadership in Florida.

US allies in Latin America and the Caribbean have also long been opposed to the embargo. In 2009, the Organisation of American States voted to unconditionally restore Cuba’s membership and urged Washington to normalise relations with Havana. Mr Obama got the same message at the 2009 Summit of the Americas, when then Brazilian president Lula da Silva warned him that “relations with Cuba will be an important sign of the willingness of the US to relate to the region”.

Mr da Silva’s choice of words is important. The embargo was widely viewed as a vestige of the US treating Latin America as a sphere of influence and reserving the right to intervene at will, overthrowing democratically-elected regimes and backing friendly dictators. And so it was not only governments of the left that opposed the embargo and its underlying assumptions. Many conservative politicians in Latin America have long conceded that Fidel Castro’s defiance of Washington resonates powerfully across the continent. The rejection of Washington’s Cold War interventionist prerogatives has even found traction in the US presidential campaign. While Hillary Clinton has made much of her endorsement by Henry Kissinger, her rival Bernie Sanders has expressly challenged the Monroe Doctrine.

“The United States was wrong to try to invade Cuba, wrong trying to support people to overthrow the Nicaraguan government, wrong trying to overthrow in 1954, the democratically elected government of Guatemala,” said Mr Sanders in a television debate with Mrs Clinton. “Throughout the history of our relationship with Latin America we’ve operated under the so-called Monroe Doctrine, and that said the US had the right to do anything that they wanted to do in Latin America. The key issue here was whether the US should go around overthrowing small Latin American countries.”

It’s worth remembering that under the Monroe Doctrine and during the Cold War, the US propped up more coups and dictatorships than it tried to overthrow in Latin America.

The end of the Cold War may have changed the strategic stakes, and where the US once coveted Latin America’s resources and markets, any business imperative undergirding the Monroe Doctrine has long since abated as China has become the dominant trade and investment partner of most Latin American economies.

So while he hasn’t lifted the embargo, Mr Obama has used his executive authority to effectively end the policy on which the embargo is based.

Rapprochement with Cuba is now an established fact, and Mr Obama’s Havana visit marks the final nail in the Monroe Doctrine’s coffin. He won’t pay any domestic political price, of course, although the same may not be true for his hosts: with the US demonstrably taking regime change off the table, it has removed the national-security argument on which the Castro regime has rationalised its repressive political system. Interesting times lie ahead on both sides of the Florida Strait.

Tony Karon teaches in the graduate programme at the New School in New York