You are weighed down by the glory of gold as you stand tall on the highest platform of the winners’ podium. To your right is a silver medallist, to your left is the winner of bronze. Just as you think you couldn’t feel any better, your national anthem blares out, accompanied by a chorus of 10,000 smartphone camera clicks.

In the modern world, few events evoke such powerful feelings of national pride as the Olympic Games.

However, in our shrunken world, ideas about nationality and citizenship are changing. Occasionally, the person representing a country at the Olympics wasn’t born in that territory and may have only very recently become a citizen of that nation.

The practice of athletes switching nationality has become common and the rising incidence of this practice is viewed negatively by some sports fans. In the 2012 Olympics, the UK recruited more foreign-born athletes than ever before and London was a particularly good games for Team GB.

Some critics of the practice of naturalising athletes began referring to Team GB’s foreign-born athletes as “plastic Brits”. Of course, the UK has no monopoly on this practice.

There are even athletes who have represented more than one nation, “treacherously” competing for and then against their birth nation.

Those opposed to this practice argue that fielding such recently naturalised citizens kills the emotional spirt of the games. If the person wearing gold on the podium can’t speak the national language and is hearing their new anthem for the first time, they are hardly likely to dissolve into patriotic joyful tearfulness.

Others are against the practice on the basis that it potentially allows wealthy nations to procure all the best talent. This could lead to a situation where the national team is as international as a typical English Premier League football club.

Rich nations, like rich football clubs, will come to dominate certain events, not through passion and perseverance, but through the all-conquering power of the purse.

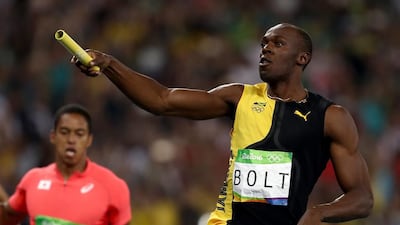

However, there are those who argue for the dissolution of national teams at the Olympics. Why do athletes need to represent countries anyway? Why can’t they just compete against each other without any reference to a nation? This is effectively saying that Usain Bolt won the 100m gold, not Jamaica. This actually resonates with the current Olympic charter, where article 6 states: “The Olympic Games are competitions between athletes in individual or team events and not between countries.”

Another argument for greater citizenship fluidity at the Olympics is that it would help get around the current – and occasionally cruel – national quota system. If you were the fifth best javelin thrower in the world, but couldn’t get a seat on the Olympic bus because the top-four ranked throwers happened to be your compatriots, you might be very happy to compete under another nation’s flag.

Similarly, advocates of a post citizenship-centric Olympics suggest that team events could simply comprise of individuals from various nations – why do I need to be a citizen of Bulgaria to represent Bulgaria?

In the modern era, some see the idea of the nation state as being a little dated.

In his book The End of the Nation State, Kenichi Ohmae, a Japanese management consultant suggests, “The nation state is increasingly a nostalgic fiction.”

Perhaps the increase in naturalised citizens competing in the Olympics is just an example of that.

Dr Justin Thomas is an associate professor at Zayed University

On Twitter: @DrJustinThomas