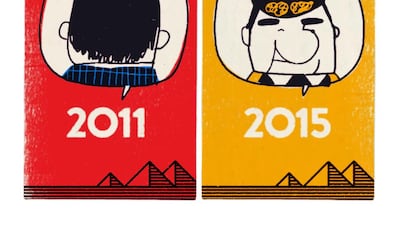

Four years have passed since Egyptians toppled President Hosni Mubarak. He sits in hospital – not a prison; all of the charges against him have been dropped and his sons have been released.

Upon the news of the court dismissing the remaining charges against the former president, Egypt’s cartoonists responded angrily. In one cartoon, a policeman yells at a prisoner: “You stole laundry and you want to get off? What, do you think you killed protesters or something?”

To understand where the troublemaking art form stands, and how cartoonists approach their new leader, we first must look at how the fear barrier was broken.

During the twilight of Mr Mubarak’s reign, Amro Selim was the first Egyptian cartoonist to tackle a juggernaut of a challenge. Selim caricatured the president himself.

Insults to the premier were (and are) illegal under Egyptian law; Selim, now 53, trod carefully back then, first drawing the back of Mr Mubarak’s head, then drawing him head on, slipping cartoons in the independent newspaper Al-Dostour, past the publisher, the de facto censor.

I wondered what Selim drew in response to Mr Mubarak’s deposal, and found myself leafing through the periodicals archive at the American University in Cairo. On February 17, 2011, Selim drew a rare self portrait: himself at the drawing board, alongside coffee and tea, paper and pen and rubber, his caricature of the back of Mr Mubarak’s neck hanging on the wall behind him.

In the cartoon, an exasperated Selim says: “There is no more Mubarak or his sons, no new presidential term, no hereditary succession.” His favourite targets were yesterday’s news. The comic version of Selim continued: “No Ahmed Ezz” – the steel tycoon and party member close to Mubarak – “No Habib El-Adly” – the former Interior Minister – “No Ahmed Nazif” – the former prime minister – “and no phoney lower house of parliament, and still no upper house of parliament.” Sweat dripping off his brow, Selim says, “What do I draw then?!” And what do Egyptians draw now?

Four years later, and again it is difficult to caricature the president. The cartoonists who have come of age since the revolution use backhanded tricks to mock President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi, or else they choose to publish their dissent online. Some cartoonists depict Mr El Sisi, but with care; others, especially in state-run newspapers, praise the president incessantly or avoid any reproduction of his likeness. Selim has included photos of the president in his work but has yet to draw him because he respects the president.

The boundaries of permissible speech are as ambiguous as ever. The red lines of acceptable humour – what can be laughed at and what must be venerated – are inscribed in penal code regulations, but the enforcement of these rules is haphazard at best.

The country’s cartooning scene reflects deep tensions in a society traumatised by revolution and counter-revolution. The day’s cartoons offer an imprecise microcosm of the political sphere.

Cartoonists like Selim, stalwart opponents of Mr Mubarak, today favour the El Sisi presidency. Twenty- and 30-something-year-old cartoonists are exploring new mediums, both in print and online. They can only publish stridently antimilitary jokes in alternative media.

The elder guard of cartoonists, those who learnt to draw during the Nasser and Sadat years, act like the revolution never happened in the first place. The pro-Muslim Brotherhood illustrators are nowhere to be found in print.

Cartooning has been important in Egypt as long as newspapers themselves. This is the country where the Arabic political cartoon came into its own as an authentically Arab medium, beginning at the end of the 19th century and reaching its heyday in the 1920s.

Today, a new Golden Age of cartoons is underway, with a range of illustrated publications on shelves, including rambunctious and revolutionary zines, graphic novels for adults, monographs of vintage political cartoonists, comic books published by art galleries and even NGOs.

Yet readers are not always pleased with the extent of criticisms being published, posing difficulties for the artists.

For Makhlouf, 32, another prolific comic artist on the daily paper Al-Masry Al-Youm, censorship comes in many forms.

“The public on the street is against us more than the state,” he told me. “When we draw, for example, about the interior ministry or the police, the people are not happy. No one from the government comes forth. But the people on social media are not happy with us.”

The secular regime in power has not made cartoonists more free to mock religion. “I don’t believe that we have a constant red line all the time,” said Anwar, 27, another cartoonist. “Drawing about religion or religious symbols or whatsoever is something that is changing. At one time, we were not able to draw a man with a beard because people on the street considered this an Islamic symbol, even if I was talking about an ordinary guy, just a man with a beard, it was some kind of extreme simplification.”

Four years have passed since the uprising and the Middle East looks radically different, though the challenges confronting Egyptians almost feel evergreen.

Back in February 2011, Selim had drawn a clothed man walking down a busy street filled with naked folks hiding their private parts; he reads a newspaper, with the headline, “The Revolution Exposes Everyone”.

Earlier this month, Selim published a cartoon of that very newspaper-reading man, his moustache now grey and his face more distraught, walking down the street, the paper’s headline being “In Remembrance of Mubarak’s Overthrow.”

Yet the eight people walking down the street are all Mubarak. Selim never thought he would draw Mr Mubarak again, yet in remembering Mr Mubarak we are transported to a world that is upside down, a world where the revolution has yet to happen. One reading of Selim’s new cartoon is that Mr Mubarak hasn’t been overthrown after all; eight Mubaraks are walking down the street. Another reading might suggest that the police state has resurged or that the people now crave the ahistorical stability that Mr Mubarak provided. Selim told me this: “The difference between the days of Mubarak or Mohammed Morsi and now, is that we now have something we have never had before, at least since Nasser: a ruler that is loved by the people.”

Jonathan Guyer is senior editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs

Twitter: @mideastXmidwest