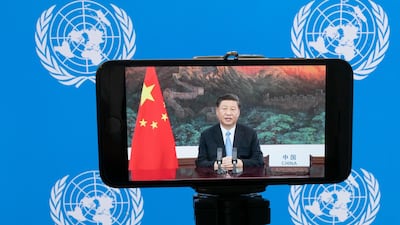

Few in the international community had expected Xi Jinping, China’s President, to announce in his speech to the UN General Assembly on Tuesday that his country intends to be carbon-neutral by 2060. Yet this is precisely what happened.

As things stand, China, the world’s largest country by population, is also the world’s largest carbon emitter. (It is worth noting, however, that in the list of countries ranked by carbon emissions on a per-capita basis, China is not even in the top 40.)

But as keen observers of China’s politics know, very little in Beijing is done by surprise. Chinese policymakers have proven to be both far-sighted and methodical. As less centralised democratic nations from the Americas to Europe to South Asia roil under the current climate of political polarisation and economic uncertainty, Beijing has afforded itself the luxury of being able to concentrate on the country’s place in the world to come.

Mr Xi was careful to express in his UN speech that Chinese emissions will, in the short term, escalate, peaking in the year 2030. To those who have campaigned for an immediate, global and maximalist intervention to put the brakes on climate change, this statement will spark alarm.

Pragmatism, however, is as fundamental to bringing about long-term change as activism. China’s level of carbon emissions, though significant, have been in large part a side effect of its efforts to achieve a stable level of prosperity for its citizens.

Between 1980 and 2005, it is estimated that the number of people in China living on less than $1.25 a day (PPP) declined by over 600 million people. The steepest decline occurred from 1999 to 2005, coinciding with the beginning of a rapid increase in the country’s carbon emissions, as more people moved into cities and industrialisation gathered pace.

Globally, the figure was just over 500 million (net poverty rates actually rose in other regions of the world, offsetting Chinese gains). The overall picture means, in a sense, that Chinese poverty reduction accounted for 100 per cent of the global total during that period. Today, China is on the cusp of eradicating poverty altogether, with the price tag clear in the form of its climbing carbon emissions.

In other words, economic well-being and carbon emissions have been linked intimately in the story of China’s development right up to today. Transforming that strategy completely is not an immediate process.

As Chinese poverty rates decline to near-zero, however, it will certainly become easier. The world approaching a point, economically and technologically, where futureproofing and development do not need to rely on carbon-heavy strategies. In fact, the experience of the UAE and the rest of the Gulf shows, the greatest investments for the long term are to be found in sustainable livelihoods. China’s carbon-neutrality goal is the strongest signal yet of Beijing’s recognition of this fact.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, China achieved the greatest poverty reduction in human history and pulled more people out of poverty than the rest of the world combined. Next year, China is expected to host the 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biodiversity, where it will showcase its role in global environmental science. With its sights set on carbon neutrality over the next 40 years, it may be China that achieves the most in reversing the course of climate change, too.