Today, voters in Iran will be turning out to cast their ballots in presidential elections. In most democratic contests, it is the final result that matters most. But for Iranians arguably the most important figures are already in: official estimates suggest that as few as 42 per cent of citizens will vote, the lowest since the revolution of 1979.

When the leader of Iran’s revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini, outlined his plans for a new republic, a defining aspect of it was a provision for presidential elections, albeit with strict oversight from powerful, unelected bodies. Nonetheless, the constrained elections are used by the regime as an outlet for people to voice their opinions, and to bolster its legitimacy. Low turnout undermines those functions, and is, therefore, not just a rejection of this year’s paltry lineup of establishment candidates, but also the country’s diminishing governing institutions more generally.

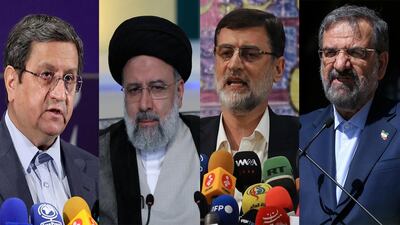

While the Guardian Council, the country’s most senior legislation and election oversight body, has always vetted presidential candidates, this year’s particularly intrusive selection process favoured the most traditional conservative figures, denying many reformists, moderates and even populist conservatives such as former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a route to office. Having started out with seven candidates, the field now stands at four. And the real contest is between just two, a more moderate former central bank governor, Abdolnasser Hemmati, and hardline Ebrahim Raisi, the firm favourite of the clerical elite.

The choice is underwhelming, but elections are one of the only safe ways left for Iranians to register dissatisfaction with the status quo. A series of leaderless protests in recent years have resulted in deadly crackdowns and no change. But if the establishment is deprived of the electoral facade it has up until now taken for granted, there is a chance politicians might actually become more wary of people’s concerns. In 2017, turnout was over 70 per cent, against today’s expected 42 per cent. It may be even smaller. Even the staunchest believers in Khomeini’s model will have confront the fact that something has gone very wrong.

In any electoral process, fragility is a feature. Public sentiment can shift rapidly as socioeconomic winds change. But when public sentiment seems to matter little at all – especially because the people voluntarily decline to cast their ballots – a different kind of uncertainty emerges.

There has been much debate among young Iranians as to whether there is any point in voting this time round. For some, squandering a ballot is unforgiveable. But there is a chance that low turnout might end up moderating one of the country’s most hardline candidates in years.

Whatever the result will be, Iran’s new president will come to power after an election that was famous for the unprecedented apathy it inspired among voters. If a well-known firebrand such as Mr Raisi becomes president when most Iranians could not be bothered to cast a vote, his brand might suddenly seem a little less fiery.