People can be forgiven for thinking less about the pandemic and the wider state of world health during the past few months. Daily global Covid-19 deaths have been falling since February, fatigue is high and a number of other non-health related crises are worthy of attention.

However, over the past few weeks a Pandora's Box of new disease threats is once again making the topic unavoidable.

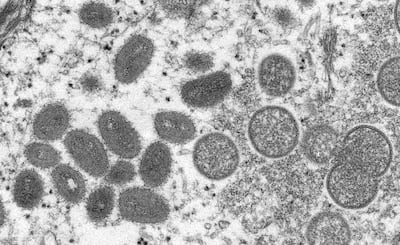

Monkeypox is a good example. Recently, cases of the disease, which is normally confined to the Democratic Republic of Congo, have been recorded in the US, the UK, Spain and Portugal. It is dangerous, with a particular strain causing death in as many as one in 10, but with human-to-human transmission uncommon, experts are clear that it does not have the same devastating potential as Covid-19.

That does not mean it cannot fit into a wider, severely dangerous threat, however. Today's concerns are not just about the arrival of another pandemic. They are also about the potential for a wave of new or resurgent illnesses.

Many of today's diseases that are worrying experts are well-known, previously well-treated and yet inexplicably on the rise. At the end of April, Pakistan recorded its first polio case in more than a year. The 15-month-old who caught it has been left paralysed. A separate case in Malawi was also traced back to Pakistan, particularly concerning given that Africa has been considered free of wild polio for some time.

The threat is not limited to poorer, less stable countries. Hundreds of acute hepatitis cases of unknown origin have been recorded in May, with more than 160 in the UK, a serious threat to babies, children and adolescents. Similar instances are being observed in wider Europe and the US. Meningitis B, also a deadly risk for young people, has spiked among British university students, too.

Disease is also posing a secondary threat to humans. Last week, Saudi authorities banned poultry imports from France because of concerns over bird flu. While the disease can on rare occasions spread to people, the biggest threat it poses today is to the world's already vulnerable food situation. With the war in Ukraine, supply chains and inflation affecting prices and availability globally, a widespread illness among livestock could be catastrophic.

There is still uncertainty as to why so many threats are emerging. Early hypothesis focus on reduced global immunity due to a lack of contact during lockdowns, interrupted vaccination regimes over the past two years and a general decline in vigilance among people after a long pandemic. The latter point applies to governments, too. Earlier this week, The National reported on Gavi, the global vaccine alliance, warning leaders not to lose focus on the threat posed by Covid-19.

The call for action is right. The world did not get healthier after the thick of the pandemic ended. Arguably, the nature of the challenge got even more complicated. Understanding the vast impact lockdowns have had on disease going forward will take years. In this context, dropping guard is irresponsible, however distracting other crises might be. Governments must continue taking threats old and new seriously, and in particular not cease research and funding into emerging illnesses.

In the tumultuous state of global health today, an important certainty remains. Since 1980, an average of three new pathogen species have been found every year. Very few of them will rival Covid-19, but even those that do not, as we are seeing today, can fit into a wider, very dangerous context if solutions to tackle them are not found. As with many of the world’s challenges, cross-country collaboration is vital for the greater good.