It has been a month since Iraq’s general elections were held. The outcome is not yet resolved, but the stakes only continue to get higher. On Sunday morning, they got deadlier, too, when an attempt was made on the life of the country’s Prime Minister, Mustafa Al Kadhimi.

It was a brazen effort. A drone packed with explosives was dispatched to Mr Al Kadhimi’s residence, in Baghdad’s Green Zone. While the exact motivation is yet to be determined, there is little doubt that the assassination attempt is linked to those who want to undermine the election results and a peaceful transfer of power based on them.

On paper, the vote was hardly a ground-shaking moment in the country's political history. Despite a big effort by the UN and western countries to boost its legitimacy, Iraqis were not convinced. Estimates suggest that just 43 per cent of registered voters turned out, the lowest number in the five elections held since 2003.

And for people looking for that rare breed of candidate willing to enact change, deciphering the field on offer was complex to the point of uselessness; more than 3,200 candidates were running in a total of 329 seats, many of them with status-quo manifestos indistinguishable from supposed rivals.

Despite popular disinterest, with economic stagnation, political infighting and deadly protests, tensions surrounding the vote were to be expected. But an attack of the kind Mr Al Kadhimi escaped on Sunday represents a new level.

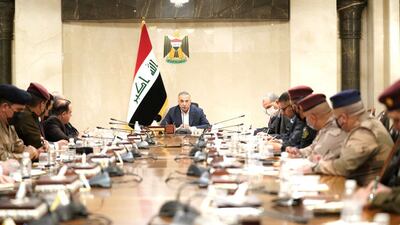

After the explosion at his residence, Mr Al Kadhimi's office issued a statement on social media reassuring Iraqis that he was safe, and calling for calm. Iraqi President Barham Salih was less reserved, calling for "unity to face the devils who want to harm the security of this country and the safety of its people”.

The exact identity of the assailants remains unclear. Iraqi sources have told The National that the drone was similar to Iranian-made ones that have been used in previous attacks. The attempt also came after violent protests outside Baghdad's Green Zone by supporters of Iran-backed militias in the country who lost out in the elections. The health ministry says 125 people were injured, of whom more than 100 were security forces.

This all comes as an increasingly violent rhetoric is peddled by certain militias against Mr Al Kadhimi, one of the few politicians who dares to criticise them, albeit carefully. The militias’ reputation has grown even more notorious since October's elections, in which the parties they back suffered an embarrassing collapse in support. But they always have their record of violence to stay relevant, and more aggression is likely to be the preferred tactic going forward.

Mr Al Kadhimi will need all the support he can get from the international community, which must be bold in calling out the role of militias in stoking tensions, along with their Iranian backers. In the case of western powers, words help but are quickly rendered useless if more is not made of the crisis in ongoing nuclear talks with Iran in Vienna. The progress of those talks will determine whether Iran is pressured into reining in its proxies. If the attempted assassination of a prime minister who enjoys broad international support is linked to groups actively supported by Tehran, then surely trust will be broken. Failing to acknowledge this would destabilise Iraq at an already fraught moment.

If Iraq’s militias and the parties who back them want a sensible voice in how the country is run, they must reject violence, corruption and the sponsorship of bloodshed by militant groups. Their enemies are ready to talk; in an impressive show of restraint and bravery, Mr Al Kadhimi issued a video statement hours after the attack, saying "I call on all sides to a constructive dialogue for Iraq and its future". After an attack on the Prime Minister, it seems that the other side is intent on rapidly going in the opposite direction.