Back in the normal, pre-coronavirus days – which seem further and further in the past – I’d pass a fire station near my home in Manhattan, New York City every day. When there were firemen outside, I would stop.

“Thank you for your service,” I’d say. It was my code for their heroism on September 11, 2001, when more than 500 of the city's first responders died. Some of them looked surprised, but most were grateful to be acknowledged for their life-saving work – to know that they mattered.

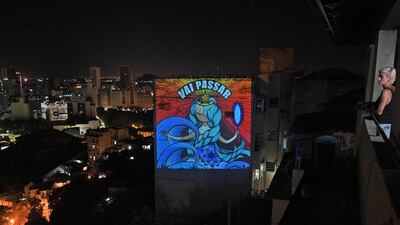

Around the world, healthcare workers, who take care of the sick and dying while knowing full well that they can catch the virus, are being lauded. In New York, Paris, Milan, Barcelona and Abu Dhabi, people are leaning out their windows and banging pots and pans, singing or cheering to boost their morale. In London, 20,000 retired National Health Service workers have come out of retirement to fight the virus.

We need to give these people concrete thanks. We need to compensate them in some way when the virus is finally contained. Every single front-line worker – every ambulance driver, every aide in a nursing home, everyone working in a triage tent, emergency room and ICU unit – is a superhero.

In the US, there is talk in President Trump’s White House about rewarding American healthcare workers with the 'GI Bill'. The term was originally a shorthand for the now-expired Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, but has since become a catch-all to refer to government-funded programmes to assist US military veterans.

In 1944, when that first GI Bill was introduced, the world was in a dark place. The Second World War had ravaged Europe and the Pacific, and new theatres of conflict had opened across the Middle East and North Africa. There was uncertainly and despair, a deep depression, hunger, poverty and overriding fear.

Fast forward to the spring of 2020. Covid-19 has now thrust the planet into a downward spiral of economic uncertainty, depression, calamity and fear. Businesses are closed. Schools are shut. Unemployment is at its highest rate in the US since the 1930s – the decade of the Great Depression. Economists are predicting the worst.

The original GI Bill allowed returning soldiers compensation for their service and their duty. It established hospitals, made low-income mortgages available, covered tuition for soldiers who wanted to return and finish their education, gave stipends.

The GI Bill, for Second World War veterans, existed until 1956. A decade later, the Readjustment Benefits Act of 1966 expanded the benefits to include all service personnel, including those who had served during peacetime. It was a way of integrating them back into society, but also a deep form of gratitude for their public service. My father bought his first house and finished his post-graduate education, all with help from the GI Bill.

The United States and other countries could very well afford the same benefits to these Covid-19 heroes. It is something that would get broad public support.

I was interested to see some of my former colleagues from my war correspondent days – John F. Burns of The New York Times and Dexter Filkins of The New Yorker – commenting that our jobs as war reporters were far easier than these front-line responders. I agree, largely because I think the latter's exposure to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder must be far greater.

Many of our journalist colleagues suffered the brutal effects of PTSD from front-line reporting. Back in 1999, I was one of the first reporters to take part in a survey, later published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, on PTSD's effect on our lives.

I was relieved to find I did not have PTSD; but most of my colleagues in the study did. If reporters suffered that much – what about these healthcare workers, who are going without sleep and witnessing so much death on a daily basis? Holding the hands of the dying, struggling to save lives against odds and the powerlessness of mounting such an insurmountable task.

Last week, I got a call from my local pharmacy in New York City. Victor, the kind man on the other end of the line, is now on the front line. The pharmacy is across the street from a major Manhattan hospital emergency room. He and his colleagues are working non-stop.

Victor was calling to tell me a mask I had ordered in early March had arrived. He was asking my permission to give it to someone else who needed it more than me. I was stunned that this man, working so hard, had taken the time to call one of his clients about a forgotten order.

I asked how he was holding up.

“We’re doing the best we can,” he replied. “We are just trying to get sick people their medicine, and help them as much as we are able. It’s not easy. But it’s necessary.”

I’ve seen too much war in my lifetime, but there is one thing I know: war, humanitarian catastrophes and pandemics bring out the worst. But they also bring out the very best in people.

They gives people a chance to be the best version of themselves, and to be of service in the most profound way.

They allow them to be selfless, and to focus on the life of another human being. If bankers on Wall Street and in the City of London were rewarded in the past for greed and avarice with enormous annual bonuses, then we can surely find a way to reward the best test of our society right now: the people keeping us alive during the coronavirus pandemic.

Today, I received an email from Yale University, where I teach, with a photo of all of the alumni working on the front line in their masks. “Superheroes don’t always wear capes,” it read. Something about that touched me deeply. I could not agree more.

Janine di Giovanni is a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and the author of The Morning They Came for Us: Dispatches from Syria