Last week a number of news outlets, including The National, reported that Twitter would hand the official account of the President of the United States to President-elect Joe Biden on January 20, whether President Donald Trump conceded the election or not.

Four years ago, readers would have been baffled that the handover was even a news story. But a lot has changed for Twitter – and world politics – since then.

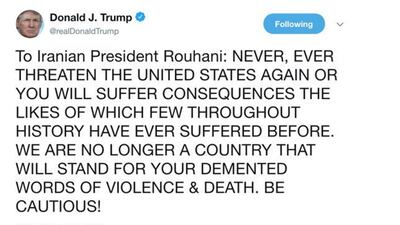

Tense geopolitical exchanges are no longer confined to press briefings and closed-door meetings. Nowadays, many of them play out on Twitter.

In 2017, one such exchange happened when North Korea announced it had a nuclear missile capable of reaching parts of the US, raising the terrifying prospect of the isolated state starting a nuclear war.

And Twitter was the primary medium through which the story developed.

From the beginning of the crisis until President Trump met the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, on June 30, 2019 – the first time a US President has met his North Korean counterpart – the world watched anxiously as tweets conveyed the highs and lows of the episode.

Notable moments included Mr Trump indirectly calling Mr Kim “short and fat”, as well as labelling him “little Rocket Man”. This was in response to Mr Kim calling him old.

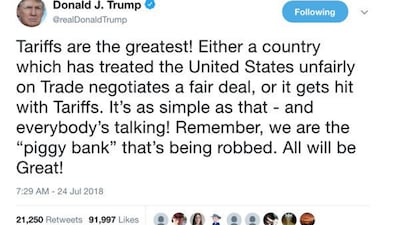

At the beginning of 2018, Mr Trump also tweeted “will someone from his depleted and food starved regime please inform Chairman Kim Jong-un that I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!”

It was a fascinating display of real-time, diplomatic venom that only something like Twitter could render possible.

But President Trump also used his tweets to take steam out of the conflict as an agreement drew near, inviting Mr Kim to “shake hands and say hello” at the border between North and South Korea, an historic event which ended up taking place.

While the entire arc of events is entertaining to some in hindsight, it is worth remembering that well-armed North Korea is capable of killing millions in minutes. In that context, the Twitter exchange was a geopolitical event in which two nuclear states edged towards major conflict and edged away again.

Twitter is also used by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to spread his ideology and attack other countries. This can include threatening to “uproot” Israel, which he describes as a “cancerous tumour”. Sometimes, such propaganda is not even disseminated by real humans. The Iranian regime has reportedly used fake Twitter accounts, or bots, to spread such material.

The irony of any tweet from an Iranian leader is that the country's citizens are banned from using the website. Policymakers in Tehran view it as too powerful a tool after its widespread use in the 2009 Green protest movement.

Political figures have also used Twitter to spread misleading information about Covid-19. After a fake-news investigation in early October, the platform was forced to take down the accounts of 16 high-profile supporters of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

____________

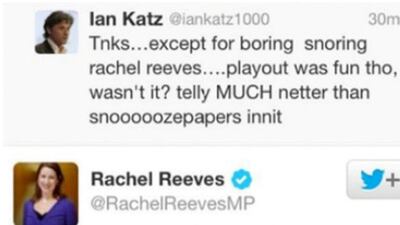

When politics goes wrong on Twitter

____________

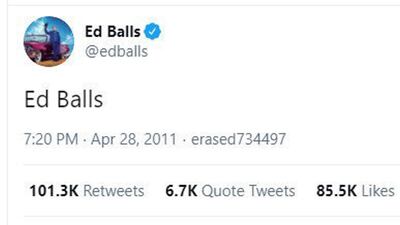

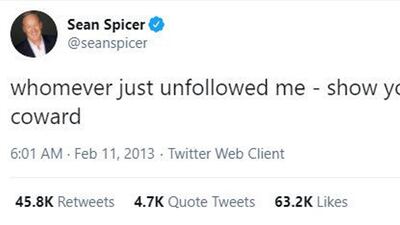

When politicians misjudge tweets, they can also invite swift ridicule. A well-remembered example occurred during Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s visit to India, when he uploaded an image of him in lavish traditional Indian clothing, including a turban. The famously politically correct leader was derided by his critics for misunderstanding modern India and even cultural appropriation.

Despite the risks, when managed correctly, Twitter is clearly a powerful tool. So it is hard to blame politicians for using it.

But some are right to worry that it accelerates a dangerous trend of 24-hour news forcing governments into rushed statements and decisions.

The 18th-century French lawyer Joseph de Maistre famously said that every nation gets the government it deserves. And with today’s expectation for leaders to be accessible 24 hours a day, can we be surprised that mistakes happen?

In the past, such a frenzied news environment was impossible. Politicians could regroup and strategise after newspapers had gone to print. This predictable system allowed for deeper planning.

In the days of a dominant mainstream media, ideas were also filtered through an outlet’s established political position, as well as rules on sourcing correctly, giving readers more clues to assess reliability and bias.

There are, of course, great benefits to Twitter. Nowadays, anyone can constructively add to dialogue, an early ideal of Silicon Valley. But we also see its exploitation by fringe voices, hostile governments and trolls.

The most important aspect of a US president’s handover to their successor – though the details are never publicised – is the transfer of codes to authorise a nuclear strike. In the US, these codes are contained in a briefcase, known as the “football”, which is carried by a military aide who never leaves the President’s side.

With much of recent years’ great power tension conducted over Twitter, it is worth considering whether a username and password are the new nuclear codes. And whether a pocketed iPhone is the new football.

There is, of course, no replacing the catastrophic power of nuclear weapons. But politicians – and Twitter itself – should remember the incredible new power they now wield.

Thomas Helm is a staff opinion writer at The National