What to make of a rising China, and the extent to which it will shape this "Asian Century", have been and will continue to be the subject of endless debate. As the current visit to Beijing of Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, shows, however, the countries of the Arabian Gulf are clear that they see opportunity and mutual benefits in deepening engagement between the Middle Kingdom and the Middle East.

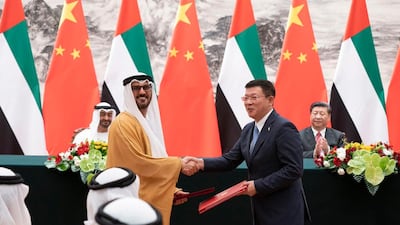

Sheikh Mohamed and President Xi Jinping witnessed the signing of at least 10 important agreements on Monday. "We share common aspirations, ambition, a vision of investment in human capital and envisage a future of safety, peace and stability worldwide," tweeted the Crown Prince.

The “promising future” that Sheikh Mohamed predicts is based not just on hopes, but on a long history. As Ni Jian, the Chinese ambassador to the UAE, wrote in this newspaper earlier this year: the “ancient connections between the Chinese and Arabs… transcend geography and cultural differences. Our ancestors, trekking across vast deserts along the Silk Road and sailing along maritime spice routes, were pioneers of friendly exchanges between nations.”

So trade and friendly relations between the two regions are nothing new, and it may have been the memory of this that led the Gulf countries to be enthusiastic and early adopters of the One Belt One Road strategy – now known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – unveiled by President Xi in late 2013.

Whereas some countries remain sceptical about this plan – which, according to a World Bank report, by 2018 included countries accounting for one third of global GDP and trade and close to two-thirds of world population – Middle Eastern strategists were swift to hail it. Dr Nasser Saidi, the former Lebanese minister who served as Chief Economist of the Dubai International Financial Centre, wrote in early 2014 of how the GCC countries should revive and build a “New Silk Road” with the aim of “embracing China, not ‘containing it’.”

“The new world order requires a reassessment of strategy and policies and a pivot to the East by the GCC countries, to be integrated into the New Silk Road,” he concluded. “There is much to look forward to in this brave new world.” This optimism was vindicated by the establishment of a "future-oriented strategic partnership of comprehensive co-operation and common development" with 21 Arab countries at the China-Arab States Co-operation Forum (CASCF) in Beijing in July 2018 and President Xi’s visit to the UAE – the first by a Chinese head of state for nearly 30 years – the same month.

The contrast with America, where anti-Chinese sentiment is fast hardening, is stark. Steve Bannon, President Trump’s former chief strategist, has helped reform the Committee on the Present Danger, an outfit that once warned about the Soviet Union, with China in its sights instead. “These are two systems that are incompatible,” said Mr Bannon of the two countries at a recent meeting of the group. “One side is going to win and one is going to lose.”

The climate, according to the New York Times, is that "from the White House to Congress to federal agencies… Beijing's rise is unquestionably viewed as an economic and national security threat and the defining challenge of the 21st century." The hostile attitude – not helped at all by Mr Trump's trade war – is self-defeating for the US, where Chinese foreign direct investment fell from $46.5 billion in 2016 to a mere $5.4 billion last year. It is also dangerous – making more likely the armed confrontations the US claims to want to avoid – and frankly stupid.

Fortunately, it is a stance that is unlikely to be replicated in the Gulf, for many reasons. Among them is the that these wealthier countries are less prone to fears of “debt traps” caused by Chinese loans than far poorer ones, in which China has come to seem a very dominant partner, such as Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. That accusation is resented by Beijing, and with some justification, for it is no more than common sense to ask governments to be responsible in taking loans for any projects, large or small.

Further, this is not a binary choice: in seeking closer ties with Beijing, the Gulf is not turning its back on the West. However, the Trump administration’s long-term engagement with the region is uncertain, with a president with strong isolationist tendencies. Second, and more broadly, it is also undeniable that commercial co-operation with the West comes with a governmental price tag. European leaders are often pressured by their electorates to try to “interfere”, as many Asian countries see it, with their cultural practices and laws.

This is not a problem with China. As its representative to the CASCF, Li Chengwen, put it last year: “The root problems in the Middle East lie in development and the only solution is also development.”

But, lastly, if the Gulf states look more to China, it is simply because they can see the results: the 20 Chinese companies who have invested more than Dh6.2 billion in the Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi since last year, to take one example; the fact that China is the UAE’s biggest trading partner, to take another.

China’s continued return to prominence is as sure a thing as the sun rising in the east. Western countries that try to put the brakes on that trajectory only make predictions of the Asian Century more certain to be borne out. The Arabian Gulf chooses differently, and chooses wisely.

Sholto Byrnes is a commentator and consultant in Kuala Lumpur and a corresponding fellow of the Erasmus Forum