This wasn't how it was supposed to end.

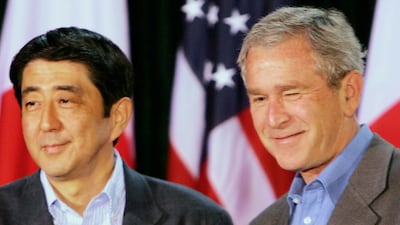

When Shinzo Abe first stepped down in 2007, only a year after becoming Japan's youngest post-War Prime Minister, two broad but mutually exclusive assumptions were made about his political future. First, he would have to settle for a ministerial portfolio in someone else's cabinet for much of his career. Or second, he was still young enough (53 at the time) to lead his party and country again when the opportunity arose. As it turned out, he returned to power five years later. And if that wasn't enough, he governed for a record, uninterrupted seven-and-a-half years thereafter.

However, as an exhausted and emotional Mr Abe last week announced his resignation for a second time, it became clear that he would leave office not with a bang but a whimper – like he did in 2007. Pledging to stay on as a caretaker prime minister until his party finds a replacement, he blamed his failing health for his decision to quit – again, like he did 13 years ago.

And yet, even though Abe 2.0 is unlikely to end with as much of an anticlimax as the beta version did, his supporters will be justified in thinking that – after dominating Japanese politics for almost a decade – this wasn't how it was supposed to end.

To understand why not, it is important to quickly recap how it began.

In 2007, Mr Abe learnt that he needed an image makeover. He had been perceived as a weak leader, presiding over a cabinet full of misspeaking, scamming and barely controllable ministers. Timing is a feature of most success stories. The long night in his career that followed his unceremonious exit coincided with a period of great tumult in Japanese politics. His successors had resigned in similar circumstances and the public had grown tired of the instability. Japan needed a strong leader, he concluded, who would run the country with an iron fist.

He united the many factions within his Liberal Democratic Party – then in the opposition – made a run for the leadership position and, with some good fortune, won the contest. Within months, he led the party to victory in the national polls.

Mr Abe came to power also on the back of a raft of promises: spearheading Japan's economic revival following "two lost decades" of stagnation; revising its pacifist constitution that bars it from going to war unless attacked first; resolving the Northern Territories dispute with Russia and securing Tokyo's bid to host the 2020 Olympics before, presumably, signing off once the Games were successfully held.

His agenda was ambitious enough and his message was clear enough to excite the public.

Another lesson Mr Abe imbibed from his first stint was never to apologise or show contrition for mistakes made by his government. It worked, but only to an extent – and when the going was good.

Periodic successes – from the victorious bid to host the Olympics to improvement in Japan's ties with China to the success in creating a 11-nation trade zone against all odds – gave the public enough reason to overlook some of the controversies that Abe 2.0 had been dragged into over the years.

But as his administration gradually began to face economic problems, it received increasingly bad press over a number of scandals. That Mr Abe’s own family was implicated in one involving an illegal fund allocation for the building of a school grated immensely with the public.

And yet, aided by the lack of a visible alternative among the splintered opposition parties, Mr Abe stood his ground in the hope that a successful Olympic Games would revive the nation’s flagging spirits and cement his legacy. As fate would have it, though, the Covid-19 pandemic has forced the postponement of the Games to 2021 – with some suggestions that it may even get cancelled.

Worse, the government has been criticised for its poor handling of the health crisis, in sharp contrast to the effective manner in which China, South Korea and Taiwan have dealt with this global challenge.

Given all this, it is fair to wonder how much longer a physically fit Mr Abe would have been able to hold on to power.

Now that he has resigned, however, a far more pertinent question concerns his legacy.

While he may be leaving office without delivering on a number of signature promises, Mr Abe's tenure is by no stretch of the imagination a failure. Much like Barack Obama's critics unfairly suggest that his only achievement remains becoming the first black US president, distilling Mr Abe's accomplishments to the singular fact that he is today Japan's longest-serving elected leader will be similarly harsh.

Indeed, Mr Abe's accomplishments are notable. He brought stability to government after a decade of tumult. His “Abenomics” policy proved moderately successful, reviving economic growth and ending a deflationary spiral.

He improved international trade with the US and reformed certain industries, notably Japan's notoriously difficult agriculture sector. And despite America's withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, he rallied together the other countries to create another trade pact – although legislatures in some countries have yet to ratify the deal.

Mr Abe's admirable determination to get more women to the workplace may have failed – as has his controversial and unpopular plan to revise the constitution.

But given Japan's labour shortage and the need for the country to bolster its national security in an increasingly multipolar world, it may be a question of when, and not if, Mr Abe's successor – whoever that may be – will be able to enact these reforms.

Despite the hits and misses, and irrespective of the imperfections, Mr Abe should be remembered for the way he conducted himself on the world stage. Former US president Harry Truman once defined a statesman as a politician who had been dead for 15 years.

Mr Abe, however, proved that you can be both a politician and a statesman at the same time. In an era of demagogues and self-styled strongmen bent on ripping up the decades-old rules-based order, the Prime Minister's leadership will be missed after he has left the stage.

Chitrabhanu Kadalayil is an assistant comment editor at The National