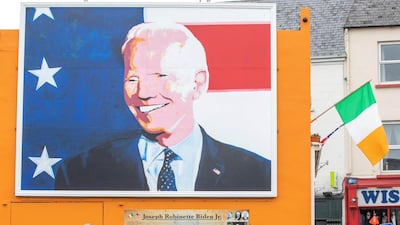

The election and inauguration of Joe Biden as US president is not only a relief to much of the world. It is also a source of pride and affection for the nearly 7 million people of the island of Ireland, the more than 3 million Irish citizens who reside overseas (of which I am one) and the 80 to maybe 100 million around the world whose identification with their Irish ancestry makes them part of a wider diaspora. For Mr Biden is the most Irish of American presidents since John F Kennedy, a fact that he is proud to mention whenever he can.

This is no mere “blarney” or “paddy-whackery”. All eight of Mr Biden’s great-great-grandparents on his mother’s side were born in Ireland, as were two of his paternal great-grandparents. He invited the Chieftains, one of the most revered Irish music bands, to play at his inauguration (they couldn’t due to travel restrictions). When he visited the country as vice president in 2016, he declared: “James Joyce wrote, ‘When I die, Dublin will be written on my heart.’ Well, northeast Pennsylvania will be written on my heart. But Ireland will be written on my soul” – no hyperbole given Mr Biden’s long commitment to the peace process in Northern Ireland.

Mr Biden also noted at the time that it was the centenary of the Easter Rising that set in motion independence for the 26 counties that make up the Republic of Ireland today. To Irish Catholics that event was a doomed but heroic attempt to end centuries of colonisation. Many Britons take a different view. The former UK defence secretary Michael Portillo has pointed out that the Rising’s leaders, whose executions took place in the middle of the First World War, had referred to Britain’s principal enemy, the Germans, as “gallant allies”.

Indeed, Mr Biden is distinct from many other presidents with Irish roots because he is only the second – after JFK – to be a Roman Catholic. Mr Biden has specifically identified as an “Irish Catholic”, and if anyone doubts that his sympathies are more with the nationalist side in Ireland, his response to a BBC reporter who’d asked him for a quick word should put them straight. “BBC?” said Mr Biden. “I’m Irish” – and walked off. He replied with a smile and was almost certainly joking. Nevertheless, it was a distinction that someone who was concerned about appealing to Irish Protestants – the vast majority of whom regard themselves as British and want Northern Ireland to remain in the UK – likely would not have made.

All of this serves to underline that Mr Biden’s affiliations mean Boris Johnson’s administration in London will need to act very gingerly around any aspect of Brexit that has an impact on the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought peace to Northern Ireland and unique cross-border arrangements with the Republic. “Any trade deal between the US and UK must be contingent upon respect for the Agreement and preventing the return of a hard border. Period,” Mr Biden tweeted last September.

Mr Johnson may have had a jolly phone call with Mr Biden recently but Micheal Martin, the Irish prime minister, appears to have spoken to him earlier. “I did invite President Biden to Ireland,” Mr Martin told CNN last Friday, “and he jokingly said to me, ‘try and keep me out.’” Under the new administration in Washington, London would do well to fear that the real “special relationship” may be with Dublin.

None of this will be lost on the many Irish people who have lived and worked in the Gulf for decades, and who have been part of my life going back to the 1980s, when my family enjoyed happy times staying with Irish friends who helped manage the Al Kharj dairy farm south of Riyadh.

What, however, will Mr Biden’s Irishness mean for the wider world? A note published by Daniel Mulhall, Ireland’s ambassador to the US, on the day of Mr Biden’s inauguration, contains some telling pointers. “In our bones,” he wrote, “we know that we are a people shaped by emigration, which has been central to the experience of being Irish for the best part of two centuries.”

Mr Biden’s maternal great-great-grandparents were born in Ireland during the 1820s and 1830s, which meant “they experienced the Great Famine of the 1840s which decimated Ireland, producing a grim harvest of death, destitution, and mass emigration.” Alluding to the fact that many Irish, especially Irish Catholics, could only enjoy true freedom outside of their homeland at that time, Mr Mulhall added that “our exiles also became a source of support for Ireland as we strove to assert our independence and cultural identity.”

I don’t think it’s too big a stretch to believe that this has informed Mr Biden’s famed capacity for empathy – that his awareness of his own ancestry instils within him a desire to be on the side of the underdog, of those who have suffered. The new president is fond of quoting Irish poets. I can imagine him speaking these lines from The Rebel, by the leader of the Easter Rising, Padraig Pearse:

“Because I am of the people, I understand the people,

I am sorrowful with their sorrow, I am hungry with their desire;

My heart is heavy with the grief of mothers,

My eyes have been wet with the tears of children….

Their shame is my shame, and I have reddened for it

Reddened for that they have served, they who should be free

Reddened for that they have gone in want, while others have been full.”

It all fits with Mr Biden’s stress on “values” and on the US leading “not merely by the example of our power, but by the power of our example”.

Now all of this needs to be tempered by the reality that many countries have very different values to America’s, and one hopes Mr Biden will be pragmatic enough not to try to enforce the US’s “example” on others.

But in these early, optimistic days of his presidency, may one not dream that Mr Biden does not entirely have to obey the dictum: “campaign in poetry, govern in prose”? That Irish soul of his is part of what has uplifted people around the world. May not just the “luck of the Irish” but that romantic muse on which he has so often drawn, remain with him.

Sholto Byrnes is an East Asian affairs columnist for The National