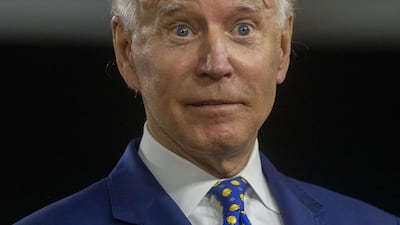

With the US presidential election now just four months away, the main question on the minds of leaders and decision-makers in other countries is to what extent Joe Biden, who is leading in the polls, will be a reincarnation of former president Barack Obama, under whom he served as vice-president. Will he erase President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, which was, in effect, an erasure of those of Mr Obama? Or is it true, as some Republicans believe, that a President Biden is more likely to continue the underlying, populist trends of the Trump doctrine, albeit rebranded with cosmetic alterations?

The eventual answer will differ between one country and another, and depends on the issues at stake. However, it is important to bear in mind that US foreign policy is more often than not rooted in the state’s long-term grand strategies, rather than the personality of a given president. For this reason, decision-makers around the world should avoid the hysteria surrounding the US election’s twists and turns.

It also seems that this election will have a very domestic focus compared to previous ones, in which foreign policy occupied a more prominent position. Perhaps one of the most telling signals of this is the speculation surrounding his vice presidential pick. Many expect Mr Biden to choose a black woman in order to secure the confidence of African Americans and to pacify the racial tensions raging across the US. Rather than Valerie Jarrett or Susan Rice, two black women who were influential foreign policy figures in the Obama administration, the speculation is that it is more likely to be Kamala Harris, a black congresswoman from California who has campaigned largely on domestic issues.

Of course, developments on the world stage can always put foreign policy back in the spotlight. In any case, the US’s rivals and allies are all planning for whatever comes next.

Beginning with Russia, Moscow has not hidden its lack of enthusiasm for Mr Biden because it worries the Democratic Party would retaliate against alleged Russian meddling in the previous election, which it partially blames for the defeat of Hillary Clinton. Moreover, the Democratic Party has traditionally accused Russia of human rights violations. The Russians would naturally be concerned about the possibility that a Biden presidency would radically alter US foreign policy, and its implications for the status quo of various hotspots around the world.

With respect to Iran, US public opinion is broadly hostile to the Islamic Republic. This is reflected in hard-line positions in Congress, which has passed laws to counter Iranian expansionist action in Syria and Iraq, as well as in Lebanon.

The Iranian leaders would therefore be mistaken if they count on luring Donald Trump into a military confrontation (even if a brief one) or ordering Hezbollah to use Lebanon to respond to Israel’s anticipated illegal annexation of Palestinian territories in September. One of the few things that unites Democrats and Republicans during US election season is a full-throated support for Israeli security. Israel is one of the few foreign policy subjects that is regarded within the US as a domestic issue, and it is unlikely that Mr Biden would dare reverse Mr Trump’s commitments to Tel Aviv under any circumstances.

Tehran is invested heavily in Mr Trump’s electoral defeat, because it believes that a Biden presidency is favourable not only in terms of reviving its nuclear deal with the US but also because it would help it normalise its relationship with European powers. Even so, however, Iranian officials are miscalculating, because European policy has moved very far in the direction of converging with US policies on Iran and Hezbollah. A Biden presidency will not move things in the opposite direction without strict conditions or accountability. It may ease some pressure in the context of sanctions, yes, but the path will be thorny, as many Trump’s policies have been codified in US law.

China, for its part, probably prefers a Biden presidency, too, given that its relations with the US under the Trump administration have become extremely adversarial. There are even accusations of Chinese meddling in the forthcoming US elections along the lines of those levelled at Russia in the previous election. But in this election, China’s and Russia’s interests diverge, with Moscow voting for Mr Trump and China voting for Mr Biden.

China’s problem is that American public opinion deeply distrusts it, particularly in light of Mr Trump’s rhetoric surrounding the supposed Chinese origins of Covid-19. Some of the more dramatic accusations circulating among Mr Trump’s supporters – and denied vehemently by Beijing – even hold that the virus was engineered in Chinese labs and allowed to leak in order to sabotage Western economies. Nevertheless, US voters’ anger at China does not mean they want any serious confrontation with it.

For other countries, the dilemma is that they are often trapped between the policies of the US and its adversaries – something that Mr Trump’s confrontational approach does not alleviate. In the standoff between the US and China, the Gulf states may find themselves in a position of having to balance their strong relationships with both. At the same time, for the majority of Arab states – other than those falling into the orbit of the Islamic Republic of Iran – a continuation of Mr Trump’s policies against Iran as well as Turkey’s support for Muslim Brotherhood could be better.

In the event that Mr Biden breaks away with the Obama legacy and largely continues President Trump’s foreign policy approach, these countries may welcome the sense of calm that might replace the Trump-era chaos. Still, the main problem handicapping US foreign policy today remains the reputation America has gained of casually abandoning its allies when it is expedient to do so. That is not something that can be blamed on any given president who serves for one or two terms. It remains to be seen whether two terms will be enough to undo it.

Raghida Dergham is the founder and executive chairwoman of the Beirut Institute