The European Football Championship is now under way across 11 cities. The matches are being played amid the jeopardy of the Covid-19 pandemic, but they have been influenced just as much by a crisis that gripped the continent more than a decade ago.

Spiralling European sovereign debt levels in 2008, triggered by the shock of the global financial crisis, resulted in some €750 billion (almost $910bn) being required by nations in assistance. Interestingly, that is the same figure that has been discussed more recently for Europe's post-Covid recovery plan.

That turbulent period more than 10 years ago was perhaps the first serious challenge to globalisation and the integration of economies that had helped spur new generations to wealth across the world, in particular in Asia.

Lowering barriers to trade and investment had supported economic growth, but it had also created systemic risk at an unprecedented scale. When the sub-prime mortgage crisis hit in the US, it triggered the equivalent of a financial tsunami that swept the globe. In such a scenario, the argument for spending billions to host a sporting event became distinctly less compelling.

Michel Platini, then president of Uefa, the European football association, understood this when he was trying to secure host countries for future tournaments. He came up with what he himself described as a "zany" solution. Rather than find one host for the 2020 tournament, Uefa would explore having multiple venues, up to 13 in fact. In effect, Platini was doubling down on the principles of globalisation, even as its very foundations were being tested and found wanting.

Two years ago, still defending his strategy, he reportedly said that “football does not exist only in France, in England or in Italy, it must exist everywhere”. That is a mantra for a globalist, if there ever was one. You could imagine the same words being said by the chief executive of any corporation in the world with ambitions to be in every market.

Such ambitions seemed achievable about 15 years ago, desirable even, given the benefits of lowering costs and lifting levels of quality. Today, successive crises, including the pandemic, have shown us that it might not be healthy to be in too many places. Ultimately, it may not even be that profitable.

Allowing homogeneity to spread unchecked undermines the in-built resilience and sustainability that can be found in local supply chains.

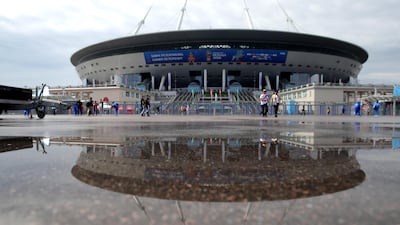

At the heart of Platini’s sales pitch was the argument that spreading Euro 2020’s 51 games in 31 days all over the continent – from Glasgow to Baku, Rome and Saint Petersburg – would make it easier for countries to come up with the funds required to be part of a showpiece that would draw a global audience. “Why should one or two host countries be obliged to build 10 stadiums, airports, et cetera? Here, there’ll be one stadium per country, per city, across Europe. It would be a lot simpler and cheaper," AFP reported Platini as saying in December 2012.

One former Fifa official observed at the time, however: "This is not what’s best for the tournament. It’s a choice imposed by the economic situation."

It was also formulated in an era when the EU had expanded to include 27 member states and there had been a boom in global air travel. It may have seemed ideal circumstances for a championship to be held on an unprecedented geographical scale. "In these days of cheap travel, anything is possible," Platini pointedly said in June 2012.

His successor as Uefa president, Aleksander Ceferin, inherited Platini's legacy. But he told The New York Times in May that he would not support a similar format again. It was complicated to pull off even before the pandemic hit, he said.

Also, Uefa is projecting that its earnings from the tournament will be at least €300 million less than forecast with fewer fans able to attend. Spreading the financial burden of hosting the tournament also spreads the risk – should something not go as planned. This is the inherent weakness of globalisation: it only works well when things are going well.

Of course, there is no reason to suggest having a single host country for Euro 2020 would have been a better solution – the debate raging in Japan over the Olympics taking place in Tokyo next month is instructive. Rather, it is worth examining if the era of global sporting events, as we have known them, is drawing to a close.

The risk from pandemics, as well as a wider acknowledgment that we must find more sustainable solutions for society, makes the traditional scale of these sporting occasions – as wonderful as they usually prove to be – obsolete.

It will be difficult for Uefa and other organisations that run their respective sports to chart a different path. But for the sake of future spectacles and the compelling drama of competition, we need to place more emphasis on staging local rather than global competitions.

Perhaps rethinking how we manage sport might also offer some much-needed productive thoughts on how to make sure that, in this post-pandemic era of globalisation, as many people as possible feel like winners.

Mustafa Alrawi is an assistant editor-in-chief at The National