Several years ago, I went to the World Economic Forum at Davos as a first-time delegate. For a Davos neophyte, it was like being in Wonderland. Riding the bus to the convention centre, a well-known international figure leaned over and confided: “The bus is the great leveller of class, wealth and society in Davos. Everyone has to ride the bus.”

Covid-19 is the opposite of that bus. In the US, we know that the more deprived communities are dying and suffering at a higher rate. And nowhere is social inequality more apparent than when it comes to the issue of education and schools reopening.

Around the world, this school year is like no other. Every country is trying to adapt to their own Covid-19 infection rates. In France, children went back to school in May in sections, depending on their age and grade. But now a second wave of the virus is hitting France as well as Germany and Spain.

In Senegal, children are sitting in isolation. In Denmark – where the crises was handled well, by banning large public gatherings and discouraging the use of public transport – children will study in isolation. In Thailand, children will stick to solitary bubbles as well.

The Centres for Disease Control in the US believes that extended school closures harm children. They claim that death rates are lower among children who do get infected. More importantly, not going back to school “disproportionately harms low-income and minority children and those living with disabilities.”

According to the CDC, these students are far less likely to have access to “private instruction and care and far more likely to rely on key school-supported resources like food programmes, special education services, counselling and after-school programmes to meet basic developmental needs.”

US President Donald Trump is encouraging schools to reopen. But as of August 17, five states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have statewide closures in effect.

Many schools say they are determined to open as long as safety comes first. They are unhappy with the Trump administration’s efforts to politicise and rush decisions. In states such as Georgia, where communities have high rates, the consequences of hurried reopening of schools could be fatal. People want their children back in the classrooms but only when it is safe.

In New York City, where I live, there is a permanent divide between the rich and the un-rich. I say this because the middle class in Manhattan has virtually disappeared. Either you have money, a car and the means to escape New York or you don’t.

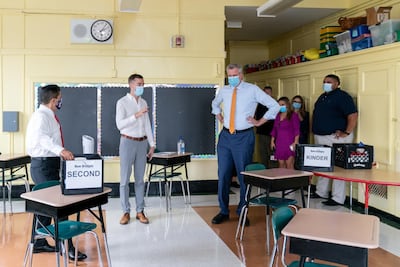

New York’s governor Andrew Cuomo announced on August 7 that based on the state’s low infection rates, he has authorised all school districts in New York state to reopen this fall for in-person education, including in New York City.

But they are based on various cohort models and depending on the model, most students will attend in-person instruction in their schools between one to three days a week. The rest of the time, students will be enrolled in remote education. They might move from “blended” learning to full-time remote learning.

There are 1.1 million students in New York City. As far as I can see, most of the wealthy have fled – either to remote hamlets upstate or to the Hamptons, the flat privileged stretch of Long Island immortalised in F Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby.

Branches of private Manhattan schools such as Avenues – a school that only teaches Spanish and Mandarin as foreign languages because they are said to be the future of finance – have opened in the Hamptons, charging $48,000 (Dh176,280) a year.

The Manhattan private elite schools are following various hybrid models. But then most of the students at schools can afford private tutoring that would give them the best education money can buy.

This is the same around the country: one wealthy California father described on CBS News how he’s partnering with other rich parents to “pod learn” their children. Each parent will pay $40 (Dh146) an hour for a private tutor to come to their home and preoccupy their children as if they were away at school.

In all of this, there are a lot of angry teachers in America. Department of Education websites claim schools have special hygiene systems, more nurses and protective equipment, and most importantly, ventilation – but a group of Brooklyn high schoolteachers protested recently, writing a letter to The Atlantic magazine saying that when "admin lie, people die."

Many universities are not going back at all, including Stanford which will teach remotely. At Yale, there is a hybrid model, and I have volunteered to teach face-to-face, albeit masked and following strict health regulations.

My first class is on September 4 and I now practise speaking for two hours a day wearing a mask.

It won’t be ideal, but I am doing it largely because I feel my students deserve it – not just because they are paying so much to go to university, but because Covid-19 has disrupted their most important years.

Not just years of learning and obtaining crucial knowledge but years of socialisation, of networking, of growing up. There is an entire younger generation – and not just the privileged – whose lives have been frozen in time, who feel they are floating in time.

We know from history that pandemics do end. And this bizarre and unsettling time will end.

But in the meantime, we need to educate a new generation who need to go out and tackle huge issues: climate change, race, human rights erosion – and most importantly – social inequality. Sure, we can do this remotely, but it is not the same. Teachers are frontline workers, essential workers, and now is the crucial time when we need to step forward.

I am a teacher and I am going back.

Janine di Giovanni is a Senior Fellow at Yale's Jackson Institute for Global Affairs. Her next book 'The Vanishing' is about Christians in the Middle East and will be published next spring