Air strikes carried out recently by British and American warplanes against ISIS targets in northern Iraq are a timely reminder that the terror group is seeking to exploit the coronavirus pandemic to carry out attacks against the West and its allies.

Following devastating defeats, including the destruction of its so-called caliphate, by the US-led coalition in Syria and Iraq in recent years, the thinking in western security circles was that the ISIS movement was in decline. This assessment appeared to be borne out by reports that it had advised its supporters to not carry out any attacks in Europe for fear of being infected by Covid-19 – an approach that also suggested the group was on the defensive.

Yet, last month's air strikes in Iraq, involving Royal Air Force Typhoon jets and American warplanes, have demonstrated that far from going into retreat, ISIS is rebuilding its organisational infrastructure. Britain’s Ministry of Defence said the strikes targeted six caves and a tunnel complex occupied by an ISIS cell in the Hamrin Mountains, north-east of the town of Baiji, killing about 10 militants.

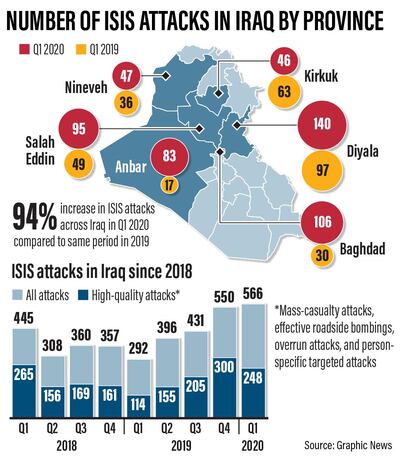

The strikes were launched amid reports that ISIS was intensifying its attacks in Iraq, a country beset by the pandemic and political paralysis following months of anti-government protests. While the group cannot match the fighting strength it displayed at its peak in 2014 – when it seized control of several provinces, as well as the strategically important city of Mosul – Iraqi security officials have reported a significant increase in attacks during the past six months.

The group is primarily focused on provinces to the east and north of Baghdad, and the organisation’s growing potency is reflected in the 108 attacks it carried out in the country in April, including an assault on an intelligence office in the city of Kirkuk. Last month, militants killed at least 10 Iraqi militiamen in a co-ordinated assault on their base in the city of Samarra.

Security officials believe there are similarities between the tactics ISIS is currently employing and those it used during the start of its campaign in northern Iraq in 2013, which ultimately resulted in the organisation controlling large swathes of the country. Its growing confidence is reflected in an online message posted by its new leader, Abu Ibrahim Al Qurashi, at the end of last month, which ominously read: “What you are witnessing these days are only signs of the big changes in the region that will offer greater opportunities than we had previously in the past decade.”

According to Lt Col Stein Grongstad, who heads the Norwegian forces involved in training the Iraqi security forces, there was a “paradox” that just as Covid-19 was weakening nations around the world, ISIS was regaining its strength in countries like Iraq. The group had, in part, managed to achieve this aim by operating in rural areas that were less susceptible to the virus.

Iraqi security officials say the number of ISIS fighters in Iraq is now between 2,000-3,000, which includes about 500 militants who have made their way to the country after escaping from prisons in Syria.

Moreover the ability of the security forces to deal with the ISIS threat has been hampered by the fact its military has seen a 50 per cent drop in the number of available military personnel as a result of the pandemic. This has enabled ISIS to shift the emphasis of its attacks from local acts of intimidation against government officials to more complex missions, including IED attacks, shootings and ambushes against the police and military.

“It’s a real threat,” Qubad Talabani, the Deputy Prime Minister of the Kurdish region of Iraq, said in a recent interview with Associated Press. “They are mobilising and killing us in the north and they will start hitting Baghdad soon.” Iraqi officials believe the upsurge is the result of US President Donald Trump’s decision at the end of last year to withdraw forces from key parts of the country.

Iraq is not the only country where there has been a noticeable increase in ISIS activity since the start of the pandemic.

In Syria, Russian warplanes have been in action after the group captured a military outpost near the border city of Deir ez-Zor. Meanwhile in Afghanistan, militants have been accused of killing more than 50 people, including mothers and newborns in the maternity ward of a hospital in Kabul.

With the primary focus of the Trump administration now directed towards domestic issues in the run-up to November’s presidential election, there are concerns in the Middle East that ISIS will take advantage of Washington’s lack of engagement in the region to strengthen its own position.

Mr Trump is understandably preoccupied with the impact of the pandemic, as well as the nationwide protests sparked by the killing of a black American man, George Floyd, in police custody in Minnesota. But he should not lose sight of the possibility that the return of ISIS could also have an adverse impact on his re-election bid.

Mr Trump was quick to claim all the credit when the caliphate was destroyed. But that could turn out to be a hollow boast if ISIS re-emerges as a major threat.

Con Coughlin is the Telegraph’s defence and foreign affairs editor