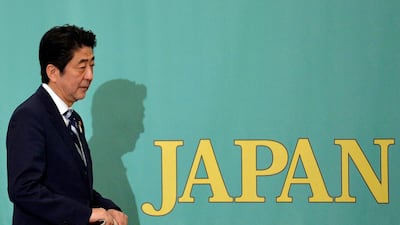

On Wednesday, less than three weeks after Shinzo Abe's resignation, Japan is all set to get a new prime minister. Yoshihide Suga's confirmation by vote in the National Diet, the country's legislature, will be considered a mere formality. So was his election on Monday as president of the Liberal Democratic Party, Japan's all-powerful ruling party that dominates not just the Diet but politics across the length and breadth of the country.

Mr Suga’s margin of victory over former defence minister Shigeru Ishiba and former foreign minister Fumio Kishida to become the LDP’s head was jaw-dropping, clinching the support of 377 of the 534 officials who were eligible to vote. But it does not necessarily mean that he is his party’s best candidate for the top job. He is simply its safest. The backroom machinations that paved the way for a Suga takeover of the party – and by extension, the premiership of Japan – have also raised eyebrows among the LDP’s rank and file and in the wider electorate. For a country that is struggling to overcome a health and economic crises, Monday’s result could be a consequential one.

To cut a long story short, the LDP's highest permanent decision-making body determined to call a special, closed election to pick the president – rather than throw it open to every card-carrying member of the party, as has been standard practice. Only the 393 Diet members and 141 representatives of the country's 47 provinces (called prefectures) could vote. Mr Abe's abrupt resignation forced this emergency procedure, the council argued, and his successor needed to be picked quickly at a time of great duress for the country and the world.

The LDP establishmentarians’ evident rush to anoint Mr Suga is a testament to his clout in the party. It also speaks to their desire for continuity and stability, given his long years spent in the Abe government. Most crucially, however, it is their fear of Mr Ishiba that forced the council’s hand. Mr Ishiba is a popular politician with considerable intellectual heft and political experience, but he is reviled by the Abe acolytes. He is seen as someone who would not hesitate to rock the boat, beginning by rolling back some of Mr Abe’s policies, and perhaps even investigating the scandals that erupted during his tenure.

While it is hard to say whether the outcome of a normal intra-party election would have been different, the contest itself would have been more even. And given how divergent the leadership styles and priorities of Mr Suga and Mr Ishiba have proved to be over the years, one can safely assume that the result will have direct bearing on how Japan is governed over the next few months, if not years.

This is not to suggest that Mr Suga would perform poorly as Prime Minister.

For a start, his life story and work ethic deserve acknowledgement. The son of a strawberry farmer, he does not belong to a political dynasty, which is seen as a helpful starting point in Japanese politics. A man who begins his day by doing a hundred sit-ups and ends it with another hundred – despite working long hours in between – clearly has the drive, the focus, the grit, and the stamina to rise to the top.

Indeed, aside from his political smarts, these are only some of the qualities, that have made Mr Suga a seasoned career politician, and an able administrator, who was widely regarded as the second-most powerful man in the Abe cabinet for almost a decade.

Mr Suga’s role as chief cabinet secretary was wide-ranging, too. He acted as Mr Abe’s press secretary, advised him on politics as well as policy, co-ordinated policies of his various ministries, and helped the Prime Minister’s Office accumulate an unprecedented amount of power by pushing through bureaucratic reform. It will not be a stretch to say that he largely ran the government from behind the scenes.

Therein, however, lies the problem for Mr Suga. His premiership risks becoming a case of “meet the new boss, same as the old boss”. And until October 2021, when the remainder of Mr Abe's term ends, the new boss will work hard to safeguard the legacy of the old boss – barring any dramas or the likely temptation to call for a snap general election.

Apart from the party’s desire for stability and continuity, there is another reason for Mr Suga to stay the course: if Mr Abe is Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, Mr Suga is the country’s longest-serving chief cabinet secretary. Their record tenures coincided for close to eight years, during which time they worked in tandem.

Together they pursued "Abenomics" that combines fiscal expansion, monetary easing, and structural reform. They expanded Japan’s tourism industry. They also advocated a more assertive and unapologetic Japan, willing to stand up to its neighbours when necessary.

The potential pitfall is that, at a time when Japan needs fresh thinking, Mr Suga has pledged to pursue these Abe-era policies, some of which have stopped yielding desired results, particularly regarding the economy. The country is struggling to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic and its tourism industry – built around the 2020 Olympics – has been kicked in the shin. Tokyo 2020 itself has been postponed to 2021 and could be cancelled altogether. Meanwhile, the "Cool Japan" strategy used by the government to project the country's soft power has taken a beating, following the government's poor handling of the pandemic.

What the country, then, needs from Mr Suga is inspirational leadership.

Through a combination of force of personality, economic reforms and nationalism, Mr Abe and his administration played an important role in Japan's recovery from the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant tragedies. Mr Suga may find out early on that he needs to be similarly consequential, although in his own unique way. It will be a task made tougher by the fact that he is more backroom dealer than mass leader and is more pragmatist than ideologue.

Most importantly, his ability to inspire will depend on the scope of his ambitions and his willingness to step out of his predecessor's shadow. To take the country with him, the new boss will need to show the public that he is not the same as the old boss.

Chitrabhanu Kadalayil is an assistant comment editor at The National