The golden anniversary of The British School Al Khubairat in Abu Dhabi, or BSAK, one of the older schools in the emirate and the UAE, was marked this week with the launch of a book written to celebrate its 50th birthday.

The setting for the launch, at the British embassy in Abu Dhabi, was both typically English and Arabian. Afternoon tea was served to a small gathering of invited guests at a site that jostles for space with such signature buildings as the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority headquarters and the 72-storey Landmark Tower, two symbols of the city's decades-long transformation from trading post to modern metropolis.

It was also an especially appropriate setting for the launch, given that the school traces its roots to the site.

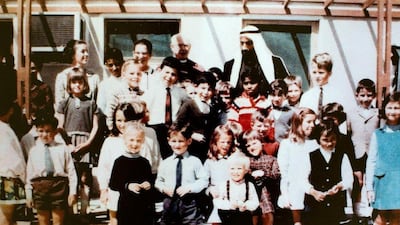

Sir Archie Lamb travelled to what was then the Trucial States in July 1965 with his wife Christina and their six-year-old daughter Kathryn to take up his post as a British political agent. His wife opened a classroom in the grounds of his office to teach the three English-speaking children who were in the city at that time. There were, in total, about 500 children in school in Abu Dhabi in the mid-1960s, spread across six schools. Kathryn, who might be described as the school’s first student (quite something when you think about it), attended this week’s book launch.

Opening that classroom in 1965 was the foundation moment of BSAK’s story, although it wasn’t until early 1968 that the school found firmer footing, when the Founding Father Sheikh Zayed donated a plot of land on the Corniche to the institution. A decade or so later, the school moved from that site to its present-day home in Al Mushrif. Sheikh Khalifa, then Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and now UAE President, became the school’s sponsor in 1980.

As the author of the anniversary book, I cannot give an impartial view on its content but what is worth discussing is what writing The British School Al Khubairat –A 50th Anniversary Portrait helped me understand about Abu Dhabi and its history.

The school’s journey from a single room in the 1960s to its provision of education for 1,900 students, aged between three and 18, at its modern campus mirrors, in some small way, the city’s trajectory. In BSAK’s 50-year history we see organic developments and great works of planning, just like in the UAE’s story. We see humbleness and generosity, but we also see key acts of strategy and clear moments of vision, again just like the country in which it sits.

We also see that, just like the city and the country itself, growth and relative prosperity were not guaranteed. Almost 50 years on from the UAE’s foundation, it would be easy to say that the modern state we live in now was bound to emerge as a success story, given the bountiful oil wealth of the country, but that significantly underplays the dedication and leadership of the Founding Father and those who have succeeded him.

That "oil wealth" narrative also washes away all the moments of great challenge the nation has endured, including the recession years in the 1980s and the far-reaching impact of the Gulf crisis sparked by the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and, more recently, the global financial crisis triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the US.

My research also revealed another similarity between the city’s story and the school.

Abu Dhabi is a forward-looking place. We see that in the country's strategy documents such as Ghadan 21, a collection of 50 initiatives announced last year by Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, which were introduced to address the priorities of citizens, residents and investors. There is an unceasing drive towards the post-oil future.

By necessity, schools are also focused on the here and now. Quite rightly, little attention is given to how the past may look when there are curriculum demands to met, timetables and teaching plans to be drawn up and even building infrastructure and development to be discussed.

All of that presents some unexpected consequences for the historian. The pace of change and development at BSAK meant that, for instance, the time capsule the school planted in 1993 with the intention of opening it during the school’s 50th anniversary celebrations is missing, presumed lost, an apparent oversight during the extensive redevelopment of the site in the early 2000s.

That story is emblematic of how the rush towards change often unwittingly brushes the past away. Many documents – some trash, some potential treasure – were also lost over the years. Fortunately, a combination of investigation and inquiry helped pull together a lot of the details of what was in the capsule. Disclosure and discovery fleshed out much of the rest of the BSAK story.

Researching the book also made me sharply aware of the brittle nature of our living history, particularly in a city and country where blank canvases are rapidly sketched in and transformation is constant. Much work has been done recently to keep the past alive through such important sites as Qasr Al Hosn and the Founder's Memorial, which both have lots to commend them. The informal nature of such social media projects as the Abu Dhabi Good Old Days help too, as does the formal work of the National Archives, but we all have a role to play if more of the past is to be preserved, even if only by being inquisitive about the way things were.

As Sheikh Zayed once said: "He who does not know his past cannot make the best of his present and future, for it is from the past that we learn."

Nick March is an assistant editor-in-chief of The National